I recently sat down with C. J. Alvarez—SAR’s 2019–2020 Mellon fellow and an assistant professor in the Department of Mexican American and Latino/a Studies at the University of Texas, Austin—to discuss his new book, Border Land, Border Water: A History of Construction on the US-Mexico Divide (UT Press, 2019). While in residence at SAR, he is working on a history of the Chihuahuan Desert that considers this area as an ecosystem rather than a political territory along a border. As we talked, I learned more about his environmental history of the border region and what he’s gaining from his time in Santa Fe.

What’s interesting about the built environment is that once something has been built, it’s very hard to imagine it not there, and the border’s a good example of this. If you’re a young person and all you’ve seen is a big pedestrian fence, the vehicle barriers, it’s making an argument to you every day, every time you see it. It becomes less and less thinkable to take it down. Even I was kind of shocked to realize the Rio Grande was straightened and all these cottonwood trees were extirpated, these levies were built, and it was basically turned into one big irrigation ditch down in southern New Mexico. I didn’t know that. Learning about the built environment is a way of recovering memory that you didn’t know you’d lost.

In October your book Border Land, Border Water was published. What is the book’s focus, and how did you approach the project?

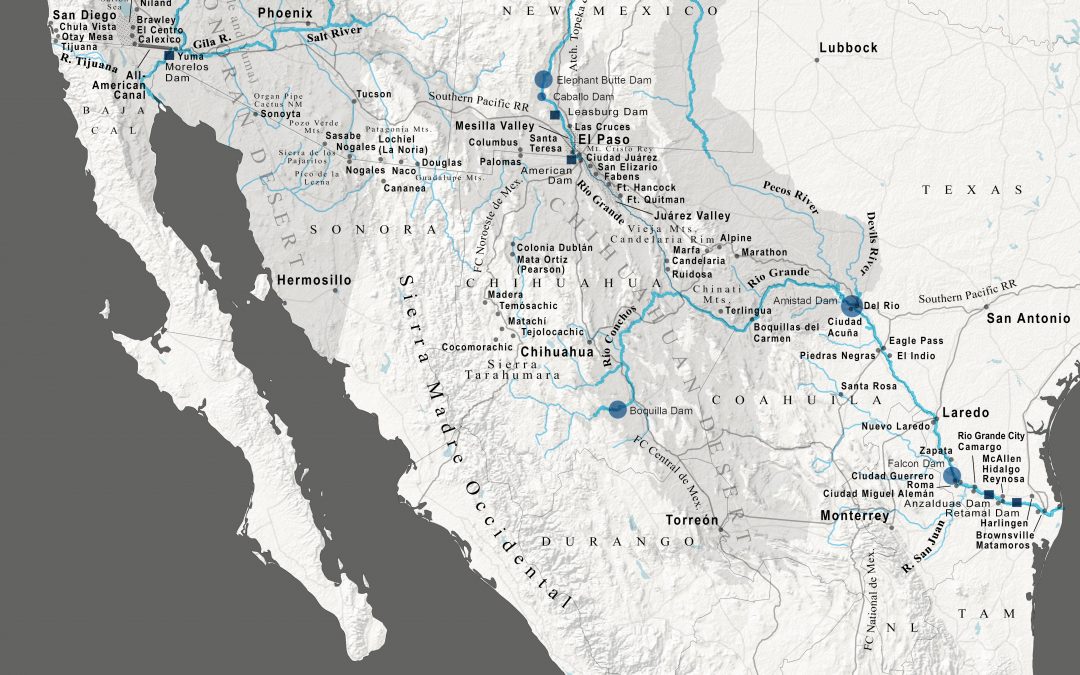

The challenge to me was to find what kind of story I could tell about the border that hasn’t already been told. The idea that I hit upon, and that gave structure to the book, was the built environment. And not the built environment of border towns, not the built environment of the extractivist industries like mining or even farming for that matter, but the built environment on the international divide itself. The argument of the book is that the border is a construction site. If you’re interested in the social and political construction of borderlands and border people, there’s also some component, I’m arguing, that has to do with the literal, physical construction of the border. Practically what that means, and the reason I divide the title between border land and border water, is that I look at building projects on the land border, the western border, and then I look at hydraulic engineering projects on the water border. It’s mostly a water border that we have between Mexico and the United States. Understanding that helps us see the border in a more nuanced way. Part of my argument is that building a fence on the land is fundamentally different than building a storage dam for flood control on the Rio Grande. Another part of what I do is look at the links that emerge between the seemingly unrelated policing projects of barrier infrastructure and projects like dam building.

I had never really thought about the difference between border projects that have to do with land and those that are built around water.

Nobody has! It was such an interesting hole in the literature. One of the more interesting conclusions that arose from the project is that if you expand your understanding of what constitutes a built environment, the river border is by far more manipulated. There are parts of the Rio Grande that have been straightened, literally. There are parts that have been lined in concrete. In the Rio Grande Valley alone, there are over 600 different drains and channels to handle flooding and irrigation and two major storage dams. The rise of the maquiladoras on the Mexican side and wastewater treatment and smelting on the US side means that the water quality is essentially different. So without being hyperbolic, you can say that the flow capacity, the discharge, the quality, the speed at which the water is moving—every cubic inch of that river has been fundamentally altered by human constructions. Now it’s not as obvious as a fence sticking out of the desert on the western border, but nonetheless, it constitutes a fundamental reorganization of the natural world, in the interest of water management and also border management.

We have been so conditioned to think about space in political terms; we forget that the main stem of the Rio Grande is actually part of a huge watershed that has other tributaries connected to it. The Santa Fe River is eventually part of border water insofar as it feeds into the main stem of the Rio Grande. Significant parts of the border are a desert, but try telling that to the folks down there in the delta who get 40 inches of rain a year and are constantly dealing with very serious flooding. “The border” is really a political concept that’s totally out of sync with the environments of the border region.

What is an example of a water project or initiative that varies from some of the typical border stories we hear in the news?

A big part of the book is looking at the history of the International Boundary and Water Commission. What’s so interesting about this agency is that it has a parallel, like a mirror image of itself on the Mexican side, called the Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas, the exact same thing in Spanish. Both of these agencies are unusual because they’re federal agencies, and most federal agencies in both countries have their headquarters in Washington DC and in Mexico City. Not the IBWC and the CILA. They have their headquarters in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua! So they’re interesting for that geographical reason, but the CILA and the IBWC are actually built through treaty law to work in lockstep so they can’t make decisions without one another. All the documentation is produced bilingually. From everything I’ve read and from informal interviews I’ve done, it seems to be the case that the commissioners on both sides, as well as the employees, kind of like each other and they have to. They work with one another in the same space. If you look at the two big storage dams, Amistad is a good example because exactly half of it is in Mexico, half of it’s in the US, half the power that it generates goes to the US, the other half goes to Mexico, half the labor came from Mexico, half the labor came from the United States, and so on and so forth. It’s a way of looking at the border that totally upends the oversimplified narrative that we hear based around antagonism and confrontation.

What was your favorite story that came out of all this research, something that struck you or stayed with you?

The thing that stayed with me the most was the relocation of the town of Zapata, Texas, and Ciudad Guerrero on the other side. Like in northern New Mexico, folks there have Spanish land grants that go back all the way to the Spanish colonial period. You know, multi-, multi-, multi-generational habitation of that one place, and the engineers come in and they say, “Look, it’s OK, we’re going to build you a whole new town, we’re going to move you.” What a lot of the literature and scholars and activists would call forced displacement. They were paid, allegedly, fair market value for their houses, and the IBWC built a whole new town for them, also called Zapata, but what was so striking to me about this story was that some of the folks there didn’t believe that what the engineers said was going to happen was possible. The engineers were saying, “The town’s going to be gone, there’s going to be water that’s 150 feet deep, right where we’re standing.”

The town was in the the reservoir zone, and you know, this is in the early 1950s. These people hadn’t been to Hoover Dam, which was built in the 1930s, they hadn’t been to the big Western damming projects. So they said, “I don’t believe you.” And some of the folks actually stayed in their doorways until the water reached their feet, and then they realized, “This is it, we gotta go.” Some of their houses were stick-frame houses, and the actual houses were lifted up and moved; a lot of them were adobes, they just dissolved. The project brought in a man from Louisiana who was a specialist in cemeteries and high water tables. He came to every house, he brought people chocolates, he brought them flowers, and he explained to them, “We’re going to dig up your ancestors.” And so not only did the engineers move the houses and the people, they moved the dead. And I think for a lot of the folks there, it was an unimaginably devastating experience.

But the project saved hundreds of thousands of people from flooding damage that they would have experienced had the dam not been there, so water projects are more ambiguous than a lot of the border stories that we’re used to hearing, which are about the overwhelming power of the American state and the relative political weakness of unauthorized migrants. The river projects caused a lot of pain, they also saved a lot of people.

Now that you’re here at SAR, you’re working on a new project, a history of the Chihuahuan

Desert. Why is this new project important to be doing now?

When I say, “I write about the border,” the response is almost always, “Oh, that’s so relevant right now.” I grew up down there, my whole family’s from down there, and we’ve been there, depending on how you measure it, for generations. So it’s always been relevant to us. And the last thing I want anybody to think is that I somehow jumped on this topic because it’s torn from the headlines. There are so many brilliant activists out there, so many political scientists, so many intrepid journalists working on the humanitarian and political implications of the border. I’m not trying to do their jobs that they’re already doing so well, and in this case I’m kind of doing the opposite. I’m ignoring the border for as long as I can, not saying it’s irrelevant, but just taking my starting point as the boundaries of an ecoregion that happens to cross the border and trying to identify not just points of friction and tension, but also commonalities between desert people on both sides of the border.

What do you hope to convey to eventual readers of the new project?

That there is such a thing as desert history. I think that what little desert history we have has been written by outsiders, and I think that in the context of climate change, studying deserts is going to be more and more important. We need to build our vocabularies, the vocabularies that we need to talk about drylands, not just here in the United States and Mexico, but all around the world. Part of that work is looking at desert peoples’ perspectives. I want to propose a different way of imagining the border region. It’s not hard to come up with criticisms for border policies, whether it has to do with immigration policing or contraband inspection or manufacturing and labor exploitation on the Mexican side, pollution, take your pick. What’s harder is proposing a meaningful alternative, and I think there might be one if we look back to history, to recover some other story that can be told that is more about cohesion than it is about tension.

As this year’s Mellon fellow, you’ve been living and working on SAR’s campus here in Santa Fe for several months now. Tell us about your time at SAR.

Oh, it’s a dream come true. I’ve always felt a very close affinity to New Mexico, growing up here, and I realized a couple years ago, I’ve actually lived more of my life outside New Mexico than I have here because I left for college and then I never lived here again. So to me, it’s not just that I have some time to breathe more deeply: living in New Mexico now really makes the difference in terms of how I’m able to focus on this new project. There are all sorts of ways that I’ve been experimenting—in addition to writing—to help me better understand the dry environment, the desert environment, to the south of here. For instance, while at SAR I’ve been studying my Audubon guide and trying to identify all the plants and all the trees and all the shrubland. Even the lizards are different here from the lizards I’m used to down south, so paying attention to those nuances helps me to be a better writer insofar as my project is to really create a sense of place as best I can.