History of SAR

Overview

SAR Administration Building

Founded in 1907 as a center for archaeological research in the Americas, SAR was revitalized in the early 1970s when it relocated to its present 15-acre campus on Santa Fe’s historic east side. Its advanced seminars and resident scholar program in anthropology and related social sciences achieved worldwide recognition, as did the quality of the Southwest Native American art collection housed in SAR’s Indian Arts Research Center. Beginning around 2010, SAR began to reinvent itself yet again. While maintaining its commitment to innovative social science, SAR has pioneered a radically participatory approach to the stewardship of its Native American art collection. It is also expanding and enhancing its educational mission in Santa Fe by offering lectures and salon discussions focused on issues of broad public concern, thus repositioning SAR as a center for creative thought in a region actively exploring new avenues of social and economic development.

The Early Years

In the early years of the twentieth century, archaeology was a young discipline with roots in the art historical studies of Old World antiquities. The unveiling of the treasures of Troy, Ephesus, and the Valley of the Kings held the world spellbound. But as the United States expanded westward, a new science sprang up in the native soils of the New World. Explorers, cowboys, missionaries, settlers, and entrepreneurs became fascinated with the remains of early Indian civilizations in the American West. Scholars from the East followed their lead to such sites as Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon. Institutional recognition was not far behind.

In 1906, Alice Cunningham Fletcher, a pioneering anthropologist and ethnographer of Plains Indian groups, was on the American Committee of the Archaeological Institute of America. The AIA, founded in Boston in 1879, had schools in Athens, Rome, and Palestine that sponsored research into the foundations of classical civilization and promoted professional standards in archaeological field work. Fletcher wanted to establish an “Americanist” center with three aims: to train students in the profession of archaeology, to engage in anthropological research on the American continent, and to preserve and study the unique cultural heritage of the Southwest. Her aims coincided with those of Edgar Lee Hewett, an innovative educator and passionate amateur archaeologist whom she met in 1906 in Mexico.

Hewett, nicknamed “El Toro,” was a flamboyant and controversial figure. He served as president of New Mexico Normal School in Las Vegas (now New Mexico Highlands University) from 1898 to 1903, where he taught some of the first courses in anthropology to be offered at any U.S. college. Hewett transformed himself from an amateur to a professional archaeologist, undertaking a doctoral program at the University of Geneva in 1903. His work as a lobbyist for the protection of archaeological sites led to the creation of Mesa Verde National Park and the passage of the Preservation of American Antiquities Act of 1906.

In December of 1907, the American Committee of the AIA accepted Fletcher’s plan to establish an American program and appointed Hewett the director of the new School of American Archaeology. Alice Fletcher was named the first chairperson of the School’s managing committee. From this institutional base, Hewett became a key architect of the discipline of Southwestern archaeology over the next forty years.

In 1909, the territorial legislature established the Museum of New Mexico as a de facto agency of the School, creating a relationship that would continue for the next fifty years. Hewett headed both the Museum and the School. In 1917 the School changed its name to the School of American Research to reflect the broadening scope of its mission.

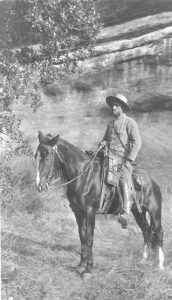

Edgar Lee Hewett at Caroline Bridge in Utah, 1907

Midway through its first year of operations, the School was already immersed in excavating twelfth- to fourteenth-century Pueblo ruins on the eastern edge of the Pajarito Plateau, west of Santa Fe, and conducting the first of its annual field programs. Many legendary archaeologists, among them Neil Judd, Alfred V. Kidder, Sylvanus Morley, and Earl Morris, received some of their training at SAR field labs at Tyuonyi Ruin on El Rito de los Frijoles (now part of Bandelier National Park), Chaco Canyon, Puye Cliff Dwellings, and other sites. The School also sponsored excavations by Morley, Morris, Judd, Jesse Nusbaum, and others in Mexico, Guatemala, and South America, and led the effort to preserve the twenty-two Spanish missions of New Mexico. From the start, the School was committed to reaching a wide audience through a program of publications, and that first year saw the appearance of its first published papers: Hewett’s “Groundwork of American Archaeology” and Morley’s “Excavation of the Cannonball Ruins in Southwestern Colorado.”

By the 1930s, university-based archaeologists began to undertake large-scale archaeological excavation projects. The School’s focus then shifted from public education to anthropological research and scholarly publication.

Through its offshoot, the Museum of New Mexico, the School took an early interest in encouraging and preserving the artistic traditions of Southwestern Indians. Indian workers assisted at the School’s excavations on the Pajarito Plateau, and their interactions with Hewett, Kenneth M. Chapman, and other archaeologists led to a recognition of individual talents and traditional aesthetics. Hewett and Chapman, an artist hired by Hewett to head the art department at New Mexico Normal School and later one of the first employees of the School of American Archaeology, were ahead of their time in their support for Indian artists, offering them studio facilities and collecting and exhibiting their work. In 1922, the School sponsored the first Southwest Indian Fair, precursor of today’s enormously popular Santa Fe Indian Market.

Fiesta Parade, 1932. Elizabeth White, resplendent in fiesta attire, sits astride her steed

Hewett led the School and Museum until his death at age 82 in 1946. A twenty-year period of relative inactivity followed as the two conjoined institutions sought to establish their separate identities and missions. This uneasy transition period ended in 1959, when the State Legislature formally separated the Museum of New Mexico from the School of American Research. The School—the original, founding organization—was gutted, left with a staff of two, an unclear mission, and an uncertain future.

A New Era

On July 1, 1967, the Board of Managers of the School of American Research appointed Douglas W. Schwartz as its new director. A young archaeologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Kentucky, Schwartz revitalized the institution and broadened its focus to embrace advanced scholarship in anthropology and the humanities worldwide and to promote the study, preservation, and creation of Southwest Indian art. At the same time, Schwartz continued the School’s tradition of archaeological research with summer field excavations in the Grand Canyon in the late 1960s and, in the 1970s, the interdisciplinary excavations of Arroyo Hondo Pueblo.

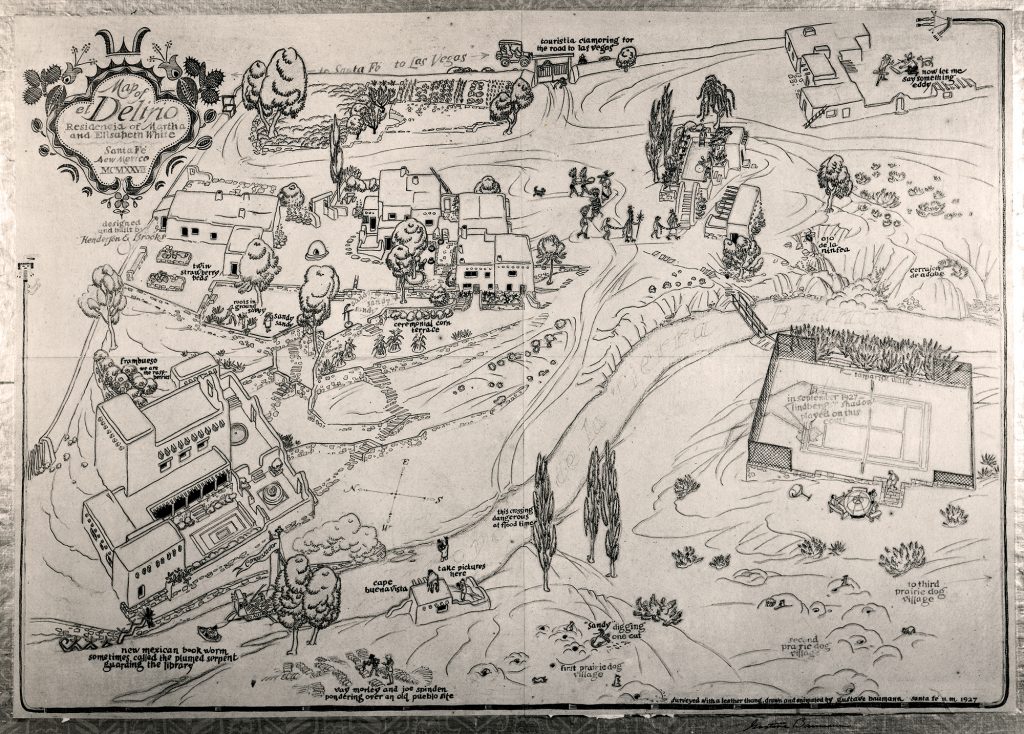

“Surveyed with a leather thong, drawn and animated by Gustave Baumann”

Over the years, SAR’s offices had relocated from the Palace of the Governors to the Museum of Fine Arts and, after 1959, to the Hewett House on Lincoln Street. In 1972 the School found a permanent home, a beautiful adobe estate on Santa Fe’s east side. “El Delirio” had been the home of Martha Root White and Amelia Elizabeth White, wealthy New York business women. Martha and Elizabeth built El Delirio in the 1920s, and it became a popular gathering place for Santa Fe artists, writers, and intellectuals—among them Edgar Hewett, Sylvanus Morley, and others closely associated with the School. The White sisters were avid patrons and promoters of Indian art, and together opened the first Native American art gallery in New York City. Elizabeth was a founding member of the Indian Arts Fund (IAF) in Santa Fe and sat on SAR’s Board of Managers for twenty-five years. Martha White died in 1937. When Elizabeth died at age 96 in 1972, she generously left El Delirio to the then-named School of American Research. In that same year, the IAF disbanded and deeded its superb collections of Southwest Indian art to SAR.

The new campus, with its extensive grounds and numerous buildings, permitted the realization of Dr. Schwartz’s vision for SAR. The Advanced Seminar Program, inaugurated in 1968, has sponsored more than 170 seminars, the results of which are published in SAR’s Advanced Seminar Series. The Resident Scholar Program, launched in 1972, has provided over 160 pre- and postdoctoral scholars with nine-month residencies in which to read, reflect, and write up research results. The construction of the Indian Arts Research Center, completed in 1978, gave the collections inherited from the IAF a suitable home. In 1979, the SAR Press began to publish independently the results of scholarship undertaken at the School, and in 1988 the J. I. Staley Prize was established to recognize books by living authors that exemplify outstanding research in anthropology.

New Century, New Directions

In 2001, SAR entered the new century with a new president, Richard M. Leventhal, an archaeologist from UCLA who assumed leadership of the School on the retirement of Dr. Schwartz. During his three-year tenure at the School, Dr. Leventhal worked to revitalize SAR’s core programs and extend greater opportunities for scholars and visiting Native artists. Dr. Leventhal was succeeded in 2005 by Dr. James F. Brooks, formerly director of SAR Press. His term coincided with the School’s Centennial in 2007, a momentous year in which SAR changed its name from the School of American Research to the School for Advanced Research, to better reflect the global reach of its support for scholarship in the social sciences and humanities. A highlight of Dr. Brooks’s tenure was an emphasis on collaborative research and exhibition projects with Native peoples.

Michael F. Brown served as SAR’s president from 2014 to 2024 after shifting to emeritus status at Williams College, on whose faculty he had long served. Dr. Brown, a cultural anthropologist familiar with SAR from his participation in two advanced seminars and a term as resident scholar, published extensively on new religious movements, the Indigenous peoples of South America, and global efforts to protect Indigenous cultural property from misuse. Under his leadership, SAR significantly expanded its public programming to include non-credit adult education classes and lectures that went beyond anthropology and archaeology to encompass social issues of broad public concern. Another key event of Brown’s term as president was Grounded in Clay, an Indigenously curated exhibition of Pueblo pottery that toured nationally.The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020-2021 led SAR to expand greatly its online presence, thus taking its programming to a broader national and international audience.

In May 2024, SAR’s board of directors announced that Dr. Morris W. Foster would succeed Michael Brown as president, effective July 1, 2024. Dr. Foster holds a Ph.D. in anthropology from Yale University. He has published on a wide range of topics, including Native American ethnography and ethnohistory, processes for community engagement, population and public health research design and policy, research ethics, and climate change. His book Being Comanche: A Social History of an American Indian Community (University of Arizona Press, 1992) was awarded the American Society for Ethnohistory’s Erminie Wheeler- Voegelin Prize for Best Book in Ethnohistory. Dr. Foster is an emeritus faculty member at the University of Oklahoma and served as vice president for research at Old Dominion University (ODU), where he led the effort for ODU to achieve Carnegie classification as an “R1” or “Very High Research” institution. Dr. Foster has served in a number of other university administrative roles as well as leadership positions for multiple non-profit organizations.

For a detailed illustrated history of SAR, see Nancy Owen Lewis and Kay Leigh Hagan, A Peculiar Alchemy: A Centennial History of SAR, 1907-2007 (SAR Press, 2007).