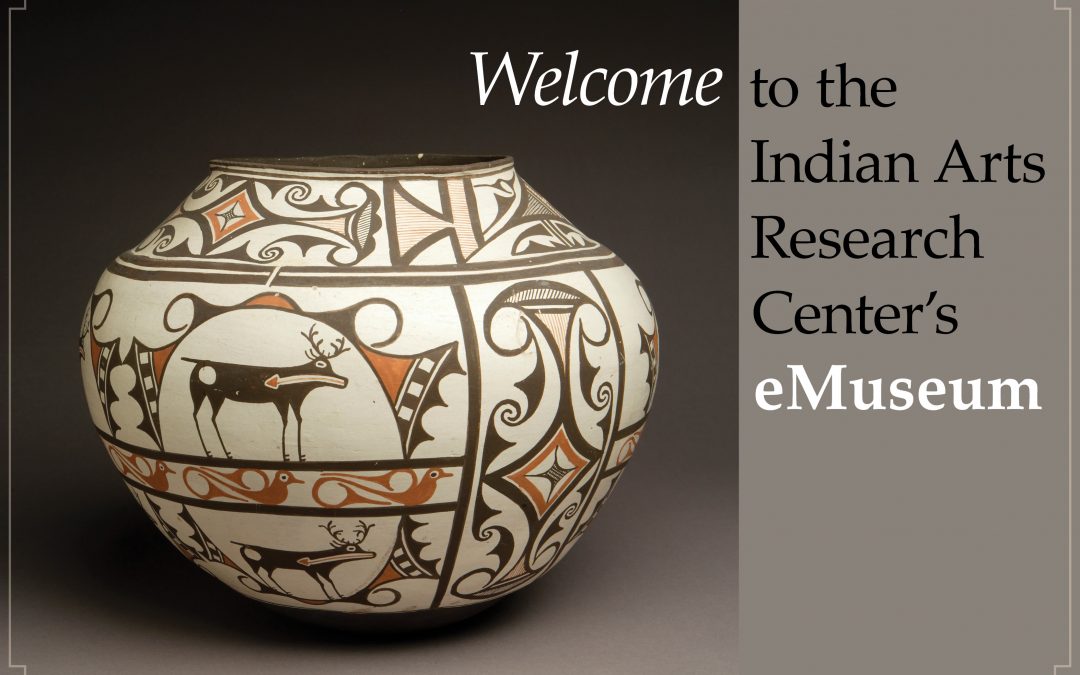

I recently walked over to the Indian Arts Research Center to talk to Jennifer Day, registrar and administrator of the collections database that stores information on the more than twelve thousand pieces of Native American art housed in the IARC. Parts of the extensive collection of Southwestern Native art are now accessible through SAR’s eMuseum, which Day was instrumental in creating. As we talked, she told me about the collections review process that contributed to the development of eMuseum.

How did the project start?

We started the reviews in 2009 with Zuni Pueblo, and we worked on that until 2015. We looked at about eleven hundred objects in the collections. Then we started work with Acoma Pueblo, and that took about five years of work with them to look at all of their objects, approximately six hundred, most of which were ceramics. The point of the project was to go to the source community to correct inaccuracies in the records and also to add information that the community participants wanted to see added to the record—things that were missing that they felt the world should know about those pieces.

IAF.1280. Pseudo-ceremonial bowl, unknown maker, Zuni Pueblo, 1920s, clay, paints. Photo by Addison Doty.

It started with Zuni Pueblo because we had some items in the collection that were labeled pseudo-ceremonial and nobody on staff knew what that meant. Why were they called pseudo-ceremonial? We had no idea. We wanted to find out what that was about so we thought the best way to do that would be to go to the community and ask them if some of these items, are they ceremonial or not? And they’re the only ones who would know that. We started working with Jim Enote and Octavius Seowtewa, and they came out and looked at the items and helped us determine that a few of those items really were ceremonial, but most of them weren’t.

We found out about that batch of items, but when we were looking at them we realized that there was so much we could learn about the whole collection by looking at each individual piece in depth like that, we decided to start this project of looking at each and every item in the collection so that we could get more information and put that point of view back in that had been missing.

So tell me what was the process, what did you actually do?

To start with, we did a lot of prep work in the database, making sure that all the objects had all the information, to make sure that was in the database so then when the participants came during the reviews, we could print out reports to give kind of a baseline of what we know about the piece. Then we would put one of those reports by each object that we pulled to look at during that session. Typically, we would go through between twenty-five and fifty pieces per session, and we would look at each piece individually with them and have them add their comments to each piece. Then after that comes the data entry stage where we add all the notes into the database in a cohesive, coherent format, and then we take that information back to the pueblo and have them read those entries to make sure that we got it right and that everyone’s on the same page about what’s being said about the object. And then any changes that need to be made at that stage can be made and then it’s considered a finished record for this purpose.

Can you think of any examples of something that was surprising or unusual?

One was a [Zuni] pot that we have three or four examples of in the collection, three or four examples of this particular design, and we thought it was just a geometric design, nice to look at, and then we found out during the reviews that they were in fact representing either a bird or a bat. So that was interesting to have a different viewpoint on it because being uninitiated into that understanding of what designs mean in that pueblo, we just didn’t know. But then when the community experts looked at it they were like, “Oh yeah, that’s a bird or a bat.” And then they explained that there are stories that go along with birds and bats and that they’re told at specific times during the year. So that was an interesting piece [of information] that opened our eyes to how little we know or how little we see without help from the source community.

Bird or bat design. IAF.248. Water jar, unknown maker, Zuni Pueblo, c. 1915, clay, paints. Photo by Addison Doty.

Rain-bird design. IAF.392. Water jar, unknown maker, Zuni Pueblo, 1880–1890, clay, paints. Photo by Addison Doty.

We found out during the Zuni review that almost all the imagery on Zuni water jars relates in some way to bird imagery or water imagery, and the birds become very abstract, but there’s one pot where this particular type of bird that’s seen in fragmentary form on other jars, the whole bird is there, kind of spelled out for you. So that was neat to look at, to see the whole bird together in one piece instead of just seeing the pieces appearing disjointedly across the jars. It’s what’s called a rain-bird design. All the birds, they said, relate back to rain so really all the bird designs are a certain kind of rain-bird design, but this is one that’s very commonly known as a rain-bird design. So it was just interesting to me to see the whole bird represented as a bird instead of just the pieces of it in designs. That was a jar I really liked because it made it very apparent where those other pieces are coming from and what they represent.

And then from Acoma, one of the things that stood out was certain designs that tend to repeat across a group of jars. We started seeing this one particular design over and over again, so we got all the jars out with that design and set them next to each other, and then the potters were explaining to us that that’s likely representing pieces by the same artist or possibly artists coming from the same family. It might have been a family design that was being passed down. Seeing the pieces next to each other really made an impact.

Did Zuni take anything back?

No, they didn’t want anything back. We identified some items that are repatriatable under NAGPRA, but at this time Zuni Pueblo doesn’t desire to have them back. Acoma Pueblo has identified some items also repatriatable under NAGPRA that they do want back, and we’re working with them to repatriate those.

What were people like when you were looking at something and they were talking to you?

I think it evoked a whole range of emotions. Most things made people happy, especially the Acoma potters when they were looking at pieces. They were just so fascinated by those things and getting to see them and touch them that for the most part I would say that the dominant emotion was happiness, but then there were some items, like I mentioned, that were repatriable under NAGPRA. When those items came up, then the mood definitely shifted to something more like, “Wow, these really shouldn’t be here,” but then that was also good for us to know because then we can send those items back home where they’re needed.

IAF.T437. Embroidered manta (shawl, eha ba’inne), unknown maker, Zuni Pueblo, 1875–1880, wool, dyes. Photo by Addison Doty.

This is a ceremonial textile that was used as a shawl or a blanket. It is a type of textile used in many pueblos, not just Zuni. This type of textile could also have been used as a dress by stitching the vertical edges together. When made into a dress, the Zuni word for it is yadonanne. When used as a shawl or blanket, it would be called ba’inne. The Zuni word eha means black in English. So, in the case of this piece, it would be called eha ba’inne, because it is a black shawl/blanket. In order to dye it a stable black, it would have first been dyed red, using dye made from the berries of a holly-like bush. It would then have been dyed using a dye made from the outer skins of wild black walnuts (found near Springerville, AZ). If it were just dyed with the black walnut skin dye, and not with the red dye first, it would have faded to gray when washed. This manta features red embroidery on the outer borders. The top and bottom borders are embroidered with a stepped cloud pattern.

In the past, this type of textile was worn as a shawl at specific times of the year. It could also be worn as a dress for everyday wear and also during ceremonies. In the contemporary context, this type of textile is no longer worn as everyday clothing and it is mostly used at ceremonial events. It is also worn during social events such as parades, Zuni dances at school, and at inaugurations. —Jim Enote and Octavius Seowtewa, collection review visit, June 10 and 11, 2009 (Events Record “Collection Review: Zuni Tribe, Review 2”)

I think you just started with another pueblo, right?

We just started working with Tesuque Pueblo.

And are you going to try to go through all of them?

Yeah, we’re going to go through all of their objects with them as well.

And through the entire collection?

That’s the idea.

And how many items is that?

Approximately twelve thousand items, so that would take the rest of my lifetime to do, literally. It’s a long, long-term project for sure.

Repeating designs. SAR.1994-4-562 (left) and SAR.1994-4-552 (right). Water jars, unknown makers, Acoma Pueblo, c. 1890, clay, paints. Photos by Addison Doty.

Tell me a bit about what you think is important about this project, about the work that you all did?

I think that for too long museum objects have been described by people not from the source communities, and while they did the best job they could, it’s not the same as having information from the source community. I think that in order to have a more accurate reflection of what a piece is or what it represents or what the designs are, you really have to go to the source community. The people there really do know what those designs mean or what they represent. And so I think trying to add back in that voice that has been missing from the collection for so long is really important.

I thought an interesting thing that came out of the Acoma collection review in particular was that since the participants were mostly potters, they went back with designs that they saw in the collection and incorporated a lot of those designs into their own work. They did their own interpretation and it helped to inform their own work, and so I thought that was an interesting way of seeing those designs carry on into the future.

Explore the collections now available on eMuseum.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

See the IARC collection, and the other treasures of SAR’s campus, by taking one of our tours.

Learn more and sign up for a tour today.

Subscribe to Voices from SAR: A Blog and receive the posts straight to your RSS feed!