Fieldwork is much more than just collecting data.

—Ben Junge

“Brazil has been a part of my life for about twenty years at this point,” says Professor Benjamin Junge, one of two 2021–2022 Weatherhead fellows now in residence at SAR. After transitioning to anthropology from his previous career in public health, he spent a summer during graduate school in Brazil studying Portuguese. “I felt like Brazil was calling out to me, and it really only took a couple of weeks before I was utterly captivated. Even to this day, I’m still very much a student of Brazil, not a Brazil expert.” “It’s a huge country,” he adds, “incredibly diverse. There’s just so much to learn and to understand, and I’ll be doing that forever, for the rest of my life.”

After completing his dissertation research in Porto Alegre, where he studied participatory democracy, Junge decided to reset his scholarly profile, “to be a beginner again.” He chose a part of Brazil he had never worked or lived in, a new set of themes, and started over. In Recife, on the northeast coast, he studied civic participation and class mobility: how they affect and are affected by gender, sexuality, race, religions, and geography.

From 2004 to 2012, through a variety of social interventions, 35–40 million Brazilians rose above the poverty line and became a “new middle class.” Beginning in 2013, however, these “once-rising poor” experienced a reversal that culminated in their support for and election of conservative politician Jair Bolsonaro in 2018. The several years leading up to the election formed the context for Junge’s current research. “I’m not trying to explain the global spread of populist conservatism,” he says, “and frankly, I tend to lean against assertions that Bolsonaro is the ‘Trump of the tropics’ if those assertions detract from understanding the specificities of Brazil’s story.” He is, instead, interested in understanding class mobility and poverty reduction from the ground up.

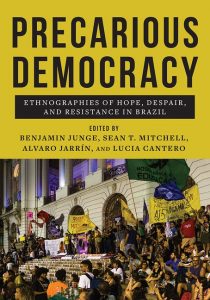

Precarious Democracy, co-edited by Benjamin Junge and published by Rutgers University Press (2021).

Brazil was still kind of riding high [in 2012–2013]. Things were looking good. The economy was strong. The Olympics were coming; the World Cup was secured. Poverty had been massively reduced in the previous decade, so it was still an optimistic kind of moment. And what everyone was talking about was this new middle class, these people who had risen out of poverty, not a lot, but just enough above the poverty line that they had a little bit of money left over at the end of the month after paying their bills that they could spend on flat-screen TV or a cell phone or maybe a cheap car. And I thought, that’s fascinating. Who are those people? What is all of this seeming progress and prosperity and poverty reduction? What does it look like from their perspective?

After their “reversal of fortune,” however, Junge’s work became less about the new middle class and their aspirations. He began to ask instead, “How do people who experienced some upward mobility, but now feel like the carpet has been pulled out from under them, understand their place in society?” This dynamic captured Junge’s attention in part because it was part of a global phenomenon playing out in places like Turkey, India, and China. And after an initial period of anxiety about how to implement a National Science Foundation–funded grant focused on Brazil’s rising middle classes, Junge realized that this situation presented him with an opportunity for a different kind, and perhaps depth, of understanding: “It’s more interesting to investigate in a moment of crisis than in a moment of prosperity—it’s more complicated, but more interesting.”

Featured image by Thamires Almeida.