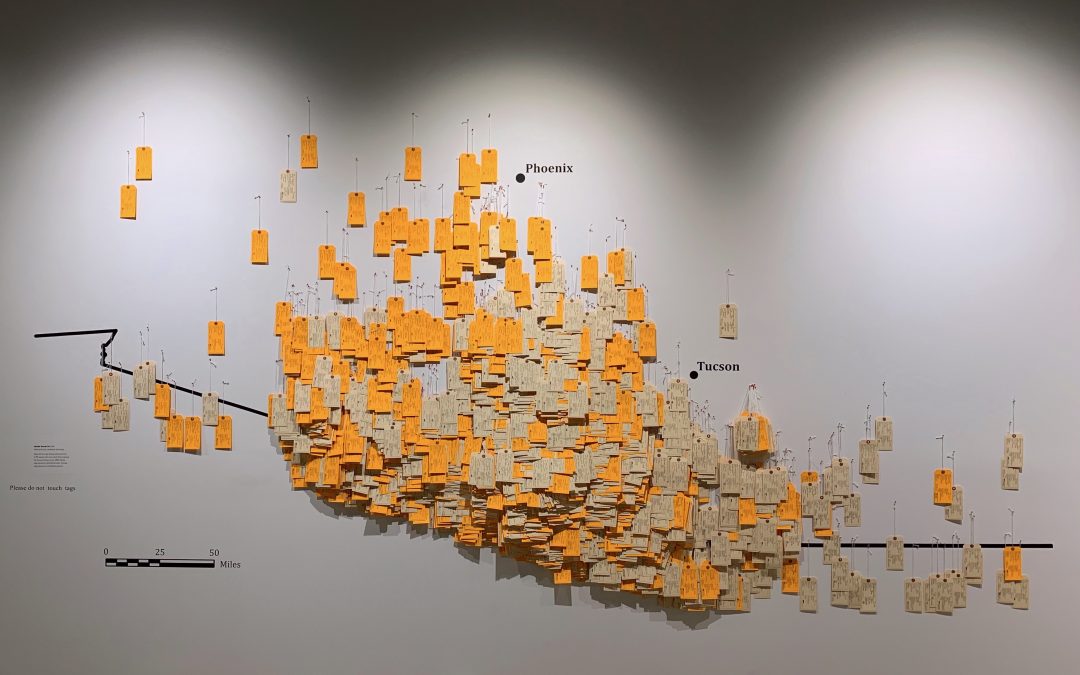

Approximately 3,200 handwritten toe tags representing migrants who died crossing the Sonoran Desert between the mid-1990s and 2019. These tags are geolocated on a map of the desert showing the exact locations where remains were found. Courtesy of the Undocumented Migration Project.

I want to empower people as much as possible, and I find the best way to do that is to encourage them to learn, encourage them to ask questions, but also find ways to bring them into this conversation and feel like they’re valued. Part of Hostile Terrain 94 is that we value people’s time and energy, and we want them to be with us in that space so they can learn with us and then go out into the world and do something new with it. — Jason De León

Jason De León, SAR’s 2013–2014 Weatherhead fellow and a 2017 MacArthur fellow, is a professor in the Departments of Anthropology and Chicana/o Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Undocumented Migration Project, a non-profit research-art-education-media collective. I recently spoke with him to learn more about his new exhibition: Hostile Terrain 94.

Jason De León speaking in front of the Hostile Terrain 94 exhibit. Courtesy of the Undocumented Migration Project.

Hostile Terrain 94, your participatory art project and exhibit, created with the Undocumented Migration Project, which represents undocumented migrants who’ve died crossing the Sonoran Desert, opens in Santa Fe in mid-July. How have the pandemic and quarantine impacted your thinking about the issue and the project, as well as the logistics of trying to get it installed?

Well, it’s forced us to regroup. We know this is an issue that’s not going away, so if we can’t directly engage with it right now that’s OK. It’s something we can continue to think about in different ways while we’re working through this pandemic, but the pandemic also brings up all these issues about how particular communities—communities of color, immigrant communities—are much more hard hit by things like pandemics. In a lot of ways it’s inspired new kinds of research questions for us: What does COVID-19 look like in detention centers? What does it look like for people who have recently been deported back to home countries? How is it impacting communities where people are trying to out-migrate right now? The pandemic has kicked off a lot of new questions for us that we’re starting to work through, and it’s also encouraged us to find ways to engage with our communities virtually. We’ve just launched a new project called Hostile Terrain 94: A Moment of Global Remembrance, where we are trying to get 3,200 people around the globe to record thirty-second videos of themselves reading the names of the dead. That’s been a good way for us to connect with these communities and to maintain attention on this issue in a safe manner.

Would you give me a little bit of background about the Undocumented Migration Project and what other kinds of work you do?

Sure, it’s a project that began in 2009, when I was teaching at the University of Washington, and it is an anthropological attempt to document and understand issues around clandestine migration from Latin America into the United States, and also to think about immigration issues around the globe. It’s a mix of archaeology, ethnography, forensic science, and linguistics, as well as taking that work and trying to translate it for a public audience in different kinds of ways: exhibitions, writing, podcasts, all kinds of mediums, but with a firm commitment to education. We have trained hundreds of students over the years in these issues, and we think about it as a mix of social science, art, outreach, and education.

People filling out toe tags with information about migrants who died trying to cross the Sonoran Desert. Courtesy of the Undocumented Migration Project.

How have the recent protests connected to the Black Lives Matter movement and the movement against police violence affected your thinking about this project?

We’re always thinking about ways to connect the structural violence that migrants experience with the structural violence that communities of color in the United States also experience at the hands of law enforcement. We think there are important parallels to make between these experiences. For example, our partners in Flint, Michigan, were interested in showing the parallels between violence in the desert and violence revolving around the water crisis and how that affects communities of color there. We’ve been thinking about it for a long time, and now I’m hoping this will be an inspiring moment—that as people have time to plan for these delayed exhibitions, they’ll be able to think more deeply about how to connect these issues.

The tactile nature of your exhibit and the recent protests—writing out the names of the dead, writing “Black Lives Matter” on the street, people out on the street, walking and using their bodies—is striking. It’s such a powerful way to learn and think about something.

That was the goal. Rather than having someone come to an exhibition and look at something put up on a wall, could we ask them to collaborate with us and be fully engaged participants? I do think there’s something meaningful about being asked to bear witness by writing out the names of the dead and at least for a moment thinking about those people and raising awareness among the living.

Detail of a toe tag from Hostile Terrain 94. Courtesy of the Undocumented Migration Project.

Why would you encourage people to get involved with work for immigration reform, and how could a person do that? What resources could they use to educate themselves or take action?

I think immigration is a pressing global issue, and it is not going away. We keep pretending that a border wall or other draconian measures are going to have some kind of an effect, but with climate change, increased political instability, and economic crises, something like COVID is only going to make immigration issues worse because people are going to have to flee different places where they’re struggling to make ends meet. As a species, whenever we’ve been faced with those situations, we’ve migrated, so I think in this current moment we need to address immigration in a way that is nuanced and thoughtful. For me, the best way to do that is to get educated. There’s no substitute for having a better sense of what it’s like out there for people who have to migrate, and I think if we can start from a place of education, then people will easily find ways to engage and to work for social change. There’s only so much I can tell you, there’s only so much that an exhibition can do for you, but I hope that those are opportunities for people to be inspired.

When people ask me what they can do right now, I tell them to look for organizations in their community. I don’t think you need to go to the US-Mexico border to work on this issue; there are immigrants in your community who need help. I think the more you know, the better: the more nuanced conversations you can have with others; the better an understanding you will have about the complexity of this issue; and the more you will realize, there’s no one thing that I can do that’s going to fix this thing, but there are a million little things I can get involved with that can be really helpful. I want to empower people as much as possible, and I find the best way to do that is to encourage them to learn, encourage them to ask questions, but also find ways to bring them into this conversation and feel like they’re valued. Part of Hostile Terrain 94 is that we value people’s time and energy, and we want them to be with us in that space so they can learn with us and then go out into the world and do something new with it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.