My father tells a story about growing up in the hill country of Texas in the forties and fifties. The train station downtown had a drinking fountain, and above that fountain was a sign that read “whites only.” He knew what it meant—no people of African or Mexican descent allowed—and that included him.

Only last week the New York Times reported on the phenomenal growth of New Braunfels, the town between Austin and San Antonio where my father grew up, as an effect of the region’s socioeconomic development. Their story story traced the town’s German heritage but said nothing about the Mexican American community’s history or contributions there. When my dad was born, Mexican American families of New Braunfels lived in the barrio seco, where water had to be carried from wells or pumps to people’s homes because the city did not provide sufficient infrastructure for all of its neighborhoods. Now New Braunfels is famous for the Schlitterbahn, a water park that contains, according to its website, a “staggering variety of river rides, waterslides, and adventures.”

Stories like these suggest questions that never seem to be fully answered: What does it means to belong? Who does, and who doesn’t? And who gets to decide?

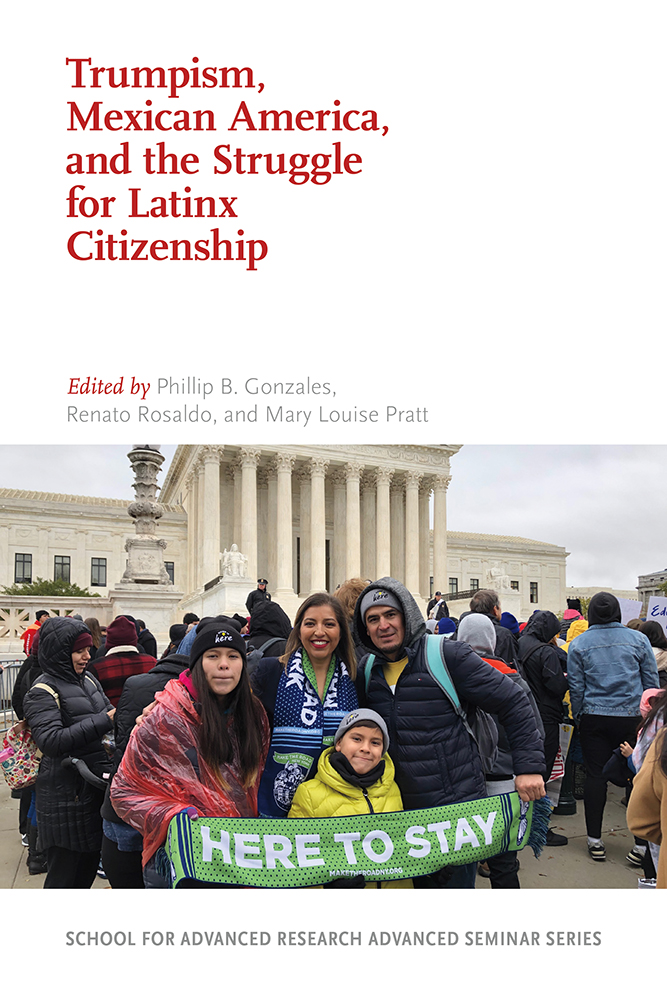

The editors and authors of our newest Advanced Seminar volume, Trumpism, Mexican America, and the Struggle for Latinx Citizenship, ask the same questions in the era of the Trump presidency. “Throughout their history in the United States, people of Mexican descent . . . have been made to question their belonging to the American social fabric and polity,” argue Phillip Gonzales, Renato Rosaldo, and Mary Louise Pratt in their introduction to the volume. Citizenship, both political and cultural, provides one lens on this question of belonging, and the contributors discuss the relationship between Latinx experience and citizenship in the United States from a variety of specific perspectives.

“For Latinx people living in the United States,” write Gonzales, Rosaldo, and Pratt,

Trumpism represented a new phase in the old struggle to achieve a sense of belonging and full citizenship. This book seeks to elucidate this new phase, especially as experienced by people of Mexican and Central American descent. At the same time, our volume situates this new phase of presidential politics in relation to what went before, and looks past this phase toward the futures that lie before us, asking what new political possibilities emerge from this dramatic chapter in our history.

Fewer water moccasins now live along the Comal River in New Braunfels, and Trump has left the White House. Trumpism, however, remains a powerful force that continues to shape our country through exclusion and violence. Join me on Wednesday, September 15, at 2:00 p.m. (MDT), to discuss this legacy with the volume editors—and to ask what opportunities for change we can identify in its aftermath.