In 1938 Edgar Lee Hewett, the first director of the School of American Archaeology (which would become the School for Advanced Research), sent Lansing Bloom to photograph the Florentine Codex at the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in hopes of producing the first complete translation of this monumental work.

“Fray Bernardino de Sahagún was the first capable ethnologist of America and if he were of the present century, he would rank with the ablest students of man, both as to method of work and recording of results,” wrote Hewett in the Papers of the School of American Research in 1944.

Sahagún “resorted to a quite unusual, even unique method, never practiced before. Fully aware of the fact that ancient Mexican history was contained in hieroglyphic signs, many of which had been destroyed . . . he made a sort of glossary in Spanish in his attempt to reconstruct that part of the ancient lore he was particularly anxious to have explained. The Indians, especially the old men, responded immediately and painted the corresponding glyphs, while the Spanish-speaking members of his advisory board explained them to him.”

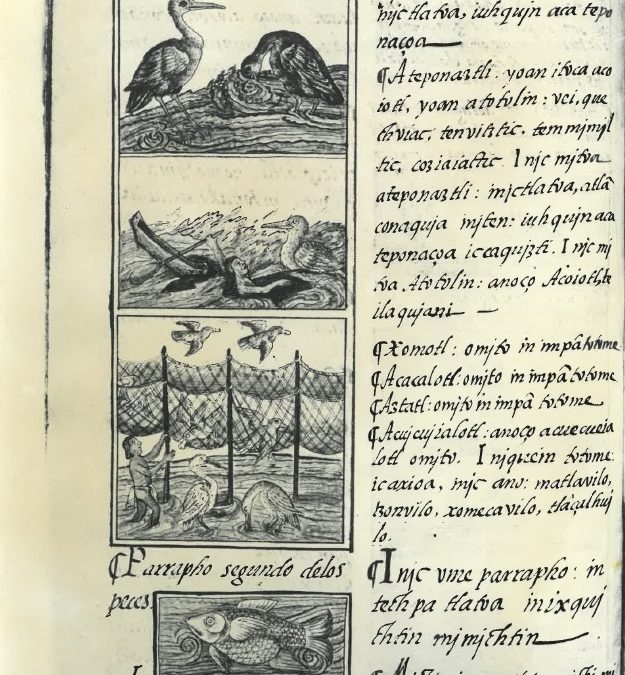

Copies of Bloom’s photographs are held in the SAR Archives and clearly show the Florentine Codex—in all its historical complexity—as a work of both scholarship and art.

The pages of the codex are now 450 years old. I wonder what the paper feels like.