SAR President Michael F. Brown (since 2014) and former SAR President Douglas Schwartz (1967-2001) on a field trip to Arroyo Hondo just south of Santa Fe in 2016. Photo courtesy of SAR.

In celebration of fifty years of Resident Scholars at the School for Advanced Research (SAR), we will share a series of posts about the program and the scholars over the years. We start today at the very beginning.

Finding and fostering a place for scholars to live, study, and write in community was the dream of archaeologist Douglas Schwartz. When he visited the School of American Research (SAR) in the fall of 1966 as “program consultant,” Schwartz was so sure he would remain in his tenured anthropology position at the University of Kentucky that he didn’t want to waste SAR’s money on an interview. When the dynamic thirty-eight-year-old shared his vision of a program of archaeology, seminars, and resident scholars that would put SAR on the map as a center for advanced study in anthropology, SAR’s Board of Managers was impressed. Schwartz was puzzled.

“How can an institution that essentially has nothing make a contribution?…What can we do? Well, we don’t have any money. We don’t have any campus. We don’t have any staff. We don’t have any programs. How can we do it?”

“I realized I’d trapped myself,” Schwartz said of his thoughts after the “consulting session.” “What I had proposed was something I really felt passionately about.”

Deliberating over the offer to direct SAR, Schwartz realized that his dream could not become reality in the “hoary tradition and bureaucracy” of a university setting. SAR was a blank slate, an opportunity to create something out of nothing.

Schwartz set to work as director of SAR in the fall of 1967, building an Advanced Seminar program as a feeder for SAR Press publications, and procuring funding to organize field work in the Grand Canyon and Arroyo Hondo. Meanwhile, Schwartz laid the groundwork for the heart of his plan: the Resident Scholar Program.

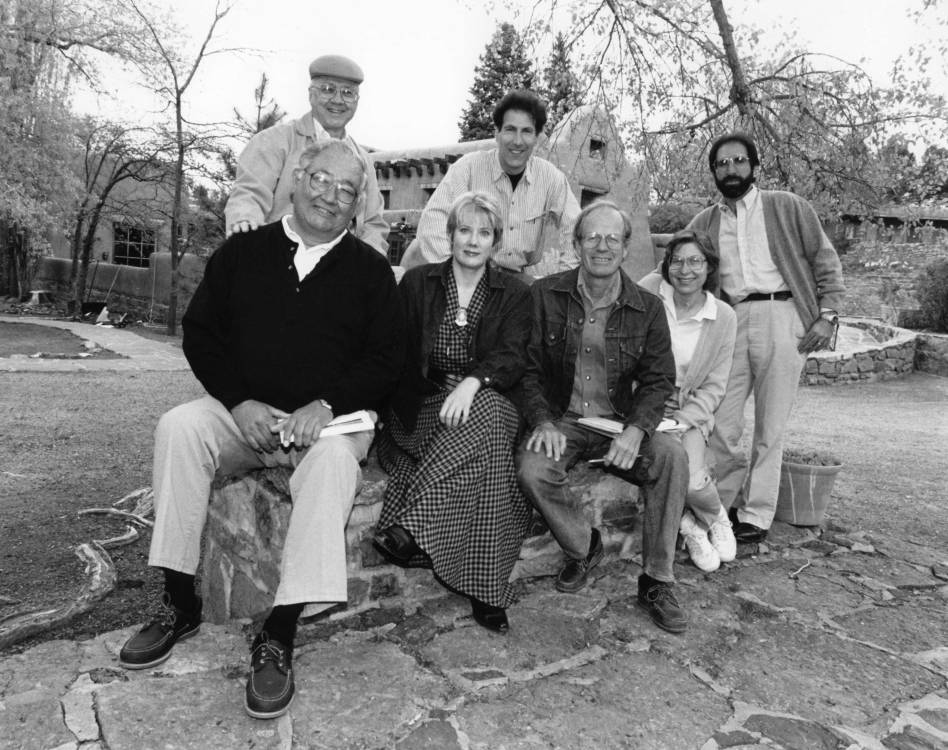

Living the dream: President Douglas Schwartz with resident scholars during their 1989-90 fellowships at SAR. Left to right, front row: N. Scott Momaday, Anna Roosevelt, Doug Schwartz (SAR president), and Linda Nicholas (wife of Gary Feinman). Back row: Art Gallaher Jr., Steven Feld, Gary Feinman. Resident Scholar Photos, SAR Records, Catherine McElvain Library, School for Advanced Research.

When the Weatherhead Foundation, a family trust, turned to the young director to learn how it could support projects in the Southwest, Schwartz introduced them to regional non-profit groups. His first request to the Weatherhead Foundation was for funding to support the posthumous publication of a book on Pueblo pottery by “art archaeologist” Kenneth Chapman, which came out in 1970. In 1972, the Weatherhead Foundation provided a $75,000 grant for a series of books on Native American arts of the Southwest.

It wasn’t until 1973, after the death of Amelia Elizabeth White and the bequest of her eight and a half acre estate teeming with buildings, that Schwartz could fully realize his resident scholar dream.

Bone-thin and nearing her mid-90s, Amelia Elizabeth would invite young Schwartz to meet with her on the little couches in her living room, today’s Dobkin Boardroom, to share stories and martinis.

“She liked the vision of a scholarly community,” Schwartz said of Amelia Elizabeth White, “and the idea that scholars might be housed here at her home.”

After Amelia Elizabeth White died on her birthday on August 28, 1972, “we had a very serious board meeting,” remembered Schwartz, “and we discussed the maintenance costs, because the bequest was for the property only. . . . I saw the property as a unique chance…to become an international organization for the support of scholarship.”

Schwartz pitched the idea to Richard W. Weatherhead, who by this time had become a friend. Nita Schwartz, Douglas’ wife, remembers that Richard and his partner would come to the Southwest every summer and they would all spend time together hiking and talking. That was how Schwartz made things happen: by making friends.

SAR moved in at 660 Garcia Street by March 1973 to the dismay of SAR’s small staff. “I wasn’t too enthusiastic about moving into this spooky, dark building,” says Schwartz’s assistant director David Grant Noble on remembering his first evening tour in dim light. Schwartz suggested Noble set-up his office in the balcony of the Chapel (now the Dobkin Boardroom). Instead, Noble’s office was in a long, glassed-in hallway where the flower plants wintered and the scholar offices are today.

In May 1973, the public was invited to an open house of the remodeled campus. Young journalist Anne Hillerman wrote an article about SAR’s new programs and location, making frequent mention of the lilacs in bloom.

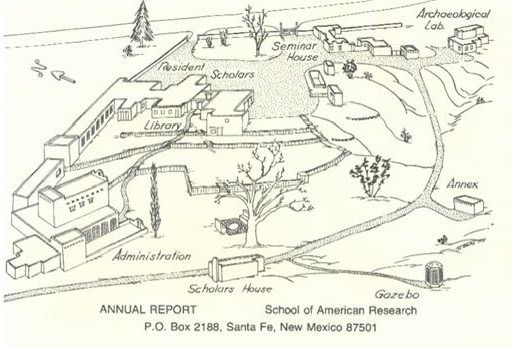

The 1974 Map of the SAR Campus demonstrates how the campus has changed over time. 1974 Annual Report, SAR Publications, Catherine McElvain Library, School for Advanced Research.

Three of the White sisters’ former guest houses were used as resident scholar homes and the nearby “New York Room” was their library.

“They got two for one,” Nita Schwartz says. In addition to raising three children and caring for several dogs and horses, Nita frequently provided dinner and assistance. She said that her husband “wanted to nurture these scholars and give them everything they needed. Where else can you get a system like that?”

“Doug’s philosophy was that they should be in an ivory tower protected from anything that would interrupt their scholarly research and reading,” Noble remembers.

Over the past fifty years, SAR has provided a scholarly haven for 278 Resident Scholars; 108 of those were Weatherhead Fellows.

That’s quite a legacy. And it all began with an idea that seemed impossible at the time.

NEXT WEEK: The First Three Resident Scholars at SAR

Sources:

1973 Annual Report of the School of American Research

1974 Annual Report of the School of American Research

Elliott, Melinda. Exploring Human Worlds: A History of the School of American Research. 1991: School of American Research Press.

Hillerman, Anne. “School of American Research to hold open house of spacious new headquarters.” The Santa Fe New Mexican. May 27, 1973.

Interview with David Grant Noble, April 25, 2024.

Interview with Nita Schwartz, April 23, 2024.

Lewis, Nancy Owen and Hagan, Kay Leigh. A Peculiar Alchemy. 2007: School for Advanced Research Press.

“SAR will have resident scholars.” The Santa Fe New Mexican. February 28, 1974.