To understand pandemics you have to know what’s going on in the small places because a pandemic is not uniform around the country or uniform by age or uniform by class or anything. It’s about hearing these specific stories about meatpacking plants and nursing homes and what Arkansas is doing versus what New Mexico is doing. In fact, it’s only when you look at those many smaller entities and populations that you actually learn what’s really moving things.

Alan Swedlund, SAR’s 1995–1996 Weatherhead scholar and professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, joined us for an online salon about viral pandemics past and present. I recently followed up with him to learn more about some of the topics he discussed in his salon.

SAR: You described how the 1918 flu coincided with or even brought about the development of public health departments and new public health measures. I wonder what new areas of society are being brought together, or brought together in new ways, by the pandemic?

AS: During the 1918 flu the established public health of the time was having a much more significant effect than it could have prior. This is when government gets more involved in general, not just in North America or the United States, but in Europe as well. China during the 1918 flu had significant political involvement, meaning a governor or a regional official being involved who wasn’t strictly in the public health arena, but they’re trying to be involved and facilitate getting through the epidemic or pandemic. So you have that going on in the early twentieth century and to some extent in Europe in the late nineteenth century, but what’s ramped up now is this infrastructure of all kinds of committees and organizations in many parts of the world, including the WHO; in the United States, the legislative branch and the executive branch, the president has his committees, and the legislative branch has subcommittees within Congress. You’ve got the National Institutes of Health, CDC, Health and Human Services, all kinds of special taskforces, and then research universities, private research, drug companies, the Gates Foundation. We now have almost instantaneous action and information and many, many bodies from different countries and organizations involved.

SAR: If the situation in 1918 was more about strengthening the public health system, what about today, when it sometimes seems like it’s everyone for themselves? Do you think there are ways in which different parts of government or other organizations are becoming stronger, or is it all sort of breaking down and separating?

AS: That’s a good question. Going back to the 1918 flu, for a place like Massachusetts, there was a board of health in place. It was actually doing things around public health in the way of improving water supplies, sewage systems, that kind of community infrastructure. Then it did ramp up for the 1918 flu very quickly, and there was communication between cities, counties, and the state. I’ve seen images of people wearing masks, just saw a really interesting one from China in 1910, I think it was. People didn’t even understand what a virus was exactly—by the early 1900s they had a concept of something beyond bacteria—but by comparison with today—the way that technology and intervention travel—the information to do these things was so much slower and the spread of the epidemics slower. With the contemporary situation, what we do see just between the Obama administration and the Trump administration is a breakdown in some organizations that were in place, governmental structures and public health structures. And we know all about the problems with the manufacturing of masks and respirators in a timely fashion.

Plagues and Epidemics: Infected Spaces Past and Present, edited by D. Ann Herring and Alan C. Swedlund, 2010.

SAR: Last night I was reading an article about polio and the history of the polio vaccine, and it was just so interesting. Part of what was interesting was the description of how grateful and beyond happy people were when this vaccine was developed. It was amazing to read about.

Year of Wonders: A Novel of the Plague, by Geraldine Brooks, 2001.

AS: Truly was, and you know I can remember, I was in junior high school having a sugar cube in a little paper cup that had the vaccine on it. It was taken orally, and you took this, then you took a booster later on.

SAR: That’s funny, my mom said the exact same thing—she could remember waiting in a line in junior high to get the vaccine. It’s been interesting to read a little bit about the scientists all over the world who are cooperating with each other and sharing information, and that’s been an interesting counterpoint.

AS: Yes, this is a time to be working together in a global world to address these pandemics.

SAR: The same article described and we see today how the pandemic affects communities differently. Did people think about how disease and inequality affect each other during past pandemics, and if so, what did they do about it?

AS: One of the old refrains that people used to say was that germs don’t discriminate, that everyone is at risk, but even in the distant past, people realized that not everyone is at risk equally. Even in the plague years, you may not have a full analysis of why you would make the choice, but if London is in the midst of plague and you have a castle out in the hinterlands, you’re going to try to get away from it. So those things have been going on for a long time. Do you know that Geraldine Brooks book Year of Wonders? She’s writing about the village of Eyam, England, during bubonic plague in the 1600s. A merchant brought in the infection, and the town as a group decided to quarantine themselves and even arranged for a way that outsiders could bring needed resources to the edge of town. Anyway, it’s a great story about how even before any notion of the germ theory of disease, people were making some pretty sophisticated responses to the threat of an epidemic. But the understanding of inequality is really quite late in other respects. Even though people and communities were aware that the rich or the people who could get away or isolate more easily would, the differential risk that we have today is so extraordinary. I wanted to start the salon by discussing the smallpox epidemics among Native Americans and Indigenous people in the 1600s because of that situation where there was such tremendous inequality and in such a powerful colonizing way. We see a continuation of risk and inequality in these groups right up to the coronavirus pandemic of today.

SAR: I have been thinking about the idea of change. If the average person goes to the store and they’re only allowed to buy one package of chicken, if we run out of masks and you have to get one from your neighbor, if the whole western half of New Mexico is under lockdown because the Navajo Nation is being hit so hard by disease, is anything going to change? I just wonder if these things are entering people’s minds on a deeper level so that they will start to ask some questions.

AS: I think they are, but again I think it varies so much by region in the country, don’t you? Where I live in the Connecticut Valley there are a lot of small vegetable farms and dairy farms and there’s an alternative for getting food, but for so many parts of the country and even in rural parts of America, like where I grew up in Colorado, there’s tons of farming and ranching but very few grow anything they eat on their farms anymore. And, you are right, access to food and good health care is still difficult for so many in this country. COVID-19 is making it worse because of rising unemployment and disruptions to supply chains and health services.

Beyond Germs: Native Depopulation in North America, edited by Catherine M. Cameron, Paul Kelton, and Alan C. Swedlund, 2015.

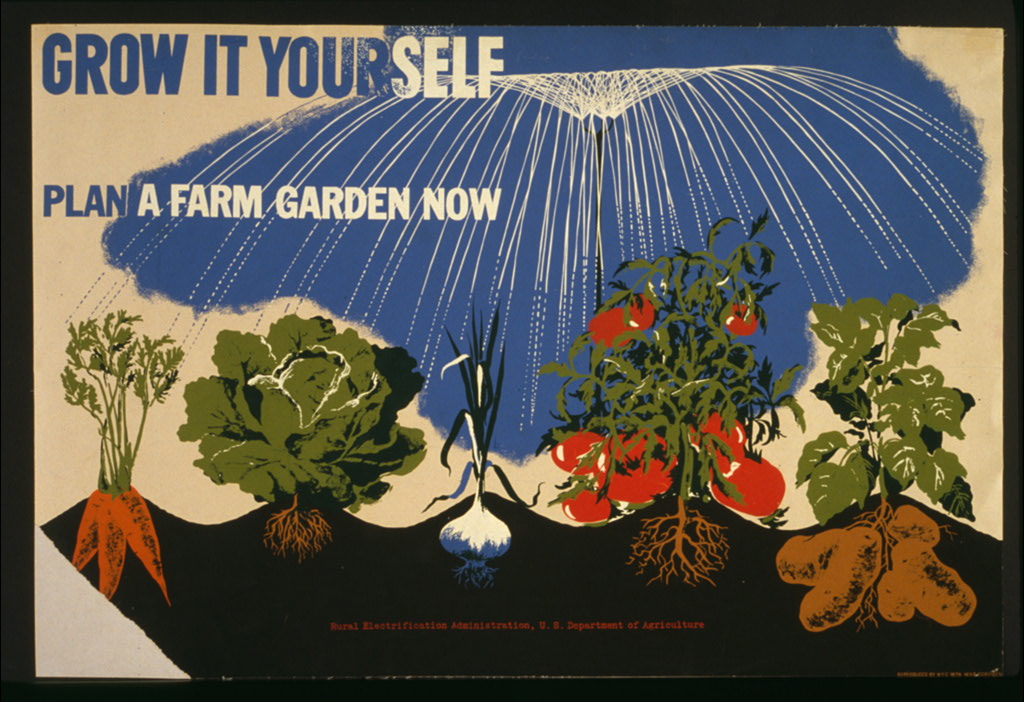

SAR: With so many people pitching in to make things and grow things and share things, I wonder if people will make any turns toward that kind of action or if they did in the past?

AS: Well, you hope so don’t you? I go up to a place called the Greenfield Farmers Cooperative Exchange to buy bedding plants and seeds, and they’re saying that they’re seeing unprecedented numbers of younger people who are coming up and buying vegetable plants and all kinds of things. Who knows whether they’ll get into it enough to do it, but it’s definitely coming around again.

Herbert Bayer (artist) and United States Rural Electrification Administration (sponsor), Grow it yourself, plan a farm garden now, WPA, photograph, 1941–1943, https://www.loc.gov/item/99400959/.

SAR: I read another story about how pandemics end. There’s a biological ending and a social ending. Are there lessons we can learn from the past about how pandemics end?

AS: One of the things about pandemics or major epidemics is that there’s a whole level of not just social, but what some people call the biopolitics of disease—the fact that it goes beyond anything that’s purely down to the public health and medical dimensions. I think it’s an interesting way of putting it, that there’s a medical ending and a social ending, and we can see that changing right now. We’re far from the end of the coronavirus, and yes, people are wishing for a social end. In the 1918 flu that was also to a certain extent true, but I think it came from a different perspective. It was more from what I call a progressive-era optimism that science is going to prevail, that we’re going to be able to get past this epidemic, more than just being frustrated by not being able to go to your local tavern or whatever it happens to be.

SAR: In your salon you said, “Anthropologists like to tackle big ideas, but they do it in small places.” What can we learn from this approach?

AS: To understand pandemics you have to know what’s going on in the small places because a pandemic is not uniform around the country or uniform by age or uniform by class or anything. It’s about hearing these specific stories about meatpacking plants and nursing homes and what Arkansas is doing versus what New Mexico is doing. In fact, it’s only when you look at those many smaller entities and populations that you actually learn what’s really moving things.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Read SAR scholar-in-residence Nancy Owen Lewis’s article about the 1918 flu epidemic in New Mexico. St. Vincent Sanatorium, photograph by Jesse Nusbaum, Palace of the Governors, Photo Archives, Neg. No. 061373.