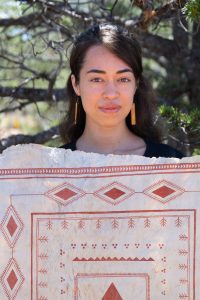

Mele O Nā Kaukani Wai (Song of a Thousand Waters), handmade plant dyes, earth pigments, and printed ‘ohe kāpala (bamboo stamps) on hand-stitched mulberry papers. Dimensions variable; approx. 13 x 8 feet installed, 2018. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Guest post by Emily Santhanam, SAR Anne Ray intern 2020–2021

Kapa is always my starting and ending point.

No matter where I go in between, it’s always something that I come back to.

—Lehuauakea

Lehuauakea lives with intention. Their artistic practice isn’t just a day in the studio, an impersonal means to a commercial end. Art and life, work and rest, discipline in technique and freedom in thought—they dissolve these boundaries.

SAR’s 2021 Ronald and Susan Dubin Native artist fellow, Lehuauakea is a Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) interdisciplinary artist. Originally from Pāpa’ikou on Moku O Keawe, Hawai’i, Lehuauakea creates traditional kapa (wauke bark cloth), which is painted or hand-stamped with patterns made from natural earth pigments and plant dyes.

Lehuauakea’s journey in kapa-making began roughly three years ago, through a decolonial, Indigenous, and personal way of learning. Their grandmother formed the root of this connection. Nearly sixty years ago, she babysat a young boy in O’ahu, Wesley Sen, who went on to become a master kapa-maker in the community. After running into him again in recent years, and with the knowledge that Lehuauakea was diving into traditional Hawaiian ways of storytelling through patterns, Lehuauakea’s grandmother suggested he become Lehuauakea’s teacher. “It’s a decolonial way of learning,” says Lehuauakea.

Rather than going to a museum or [taking] a workshop to learn about this in a day or two, really making connections with people that know your family or know your family friends, and learning from them in person—it was a whole different experience.

Uncle Wes, as Lehuauakea calls him, has grounded the technical and process-based work that they do. Kapa-making is a labor- and time-intensive art, involving knowledge of the plants, land, and ecosystem of a place. Because the tradition of kapa is not specific to Hawai’i and extends throughout the Pacific, different locations have developed unique ways of processing the materials. Alongside these cultural and geographic nuances, certain families also pass down patterns that tell stories and hold symbolism rooted in their communities.

Lehuauakea uses a variety of patterns when stamping and painting on kapa. Some of their work references carved pattern tools from two to three hundred years ago and incorporates designs from tattoos and material crafts dating back at least two thousand years. Yet because many of these patterns have lost their meaning or were stolen through colonization, copying these designs today can be considered inappropriate.

What I’ve been taught to do is look at those patterns and acknowledge where they’re from, and look at the epistemology that birthed them in the first place, and use those ideas and aesthetics to create new patterns that reflect my own experience, my own background, and the environment that I’m currently in.

In their work on SAR’s campus, Lehuauakea is drawing from a select few older patterns, while primarily creating new designs. They reference the plants, animals, and elements of Santa Fe, as well as dreams and other spiritual visions. As a Native Hawaiian, Lehuauakea was taught to honor the strength and power of these forms of expression and chooses not to plan their designs beforehand.

At times, patterns emerge through a dream or vision fully formed and ready to be painted or stamped. Lehuauakea’s most recent finished piece at SAR worked this way: when they saw a red diamond in a dream vision, they understood it needed to be translated to kapa.

When preparing paints and dyes, Lehuauakea strongly prefers earth pigments. They’re more stable and less reactive to environmental factors like light, air, and acidity, which makes them more forgiving to work with. They also necessitate a deeper interaction with the ecosystem and environment in which an artist works. Given that Lehuauakea lived in Portland for most of their practice, they harvested the majority of their pigments in and around Oregon. They feel a responsibility to resist Western extraction narratives, fostering instead a dynamic relationship with the land.

Lehuauakea making kapa at SAR.

This sense of responsibility extends well beyond their interactions with materials. As the first kapa-maker in their family line for at least seven generations, Lehuauakea understands that this knowledge is a gift. They honor the teachings that were passed down through Uncle Wes and hope to carry kapa-making forward for future generations.

In my culture and my upbringing . . . responsibility roots us to our purpose within a community. Honoring those responsibilities is how we honor ourselves and honor each other.

While Lehuauakea is still developing their own kapa-making practice, they now have the tools to guide younger practitioners in the Pacific Northwest. Providing knowledge and opportunities to a community that might feel displaced from their Hawaiian homelands and culture allows Lehuauakea to ground their teachings. They emphasize Indigenous knowledge and site-specific mythologies, expanding the meaning of “research” beyond the archives. Lehuauakea is generous yet discerning with their knowledge, careful about the institutions they engage and hold space with: “As an Indigenous artist, I have to honor my boundaries and understand that the work that I do is not living within a microcosm of just myself: it’s a larger picture.”

Artist wearing their mixed-media work, ‘A’ahu Ho’okahuli Aupuni (Cloak of the Revolution), featuring hand-sewn embroidery and shells on kapa, kimono silk, and bridesmaids’ dress fabric. Image courtesy of Moriel O’Connor.

At SAR, Lehuauakea has been able to live and make kapa at their own pace: beating mulberry in the quiet of campus, air-drying finished cloth in the desert sun, and hand-painting sans city distractions. This time of relative stillness has helped crystallize their goals, making space for their upcoming residency with the Burke Museum and Pacific Islander Community Association of Washington. The kapa they’re preparing now will move with them to Seattle and inform their residency in September. It’s both the starting and ending point of their journey—something they always come back to.

Lehuauakea is in residence at SAR through August 15, 2021. They will be presenting a free virtual artist talk on Thursday, August 12, at 5:30 p.m. (MDT).