Guest post by Emily Santhanam, SAR Anne Ray Intern 2020-2021

We began the class with an exercise in humility: writing down our thoughts and beliefs about Greenwood, and comparing that with broad assumptions, rumors, and questions. As I bisected my notebook page and put pen to paper, I swiftly realized that I knew next to nothing about the real history of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma. After living in the state for three and a half years, even after reading headlines and articles about the recent search for mass graves, I was still overwhelmed by hearsay and myth. Professor Dr. Alicia Odewale met us where we were – ignorance and all – and built upon our fragments of knowledge, propelling the course toward a reckoning with truth and healing.

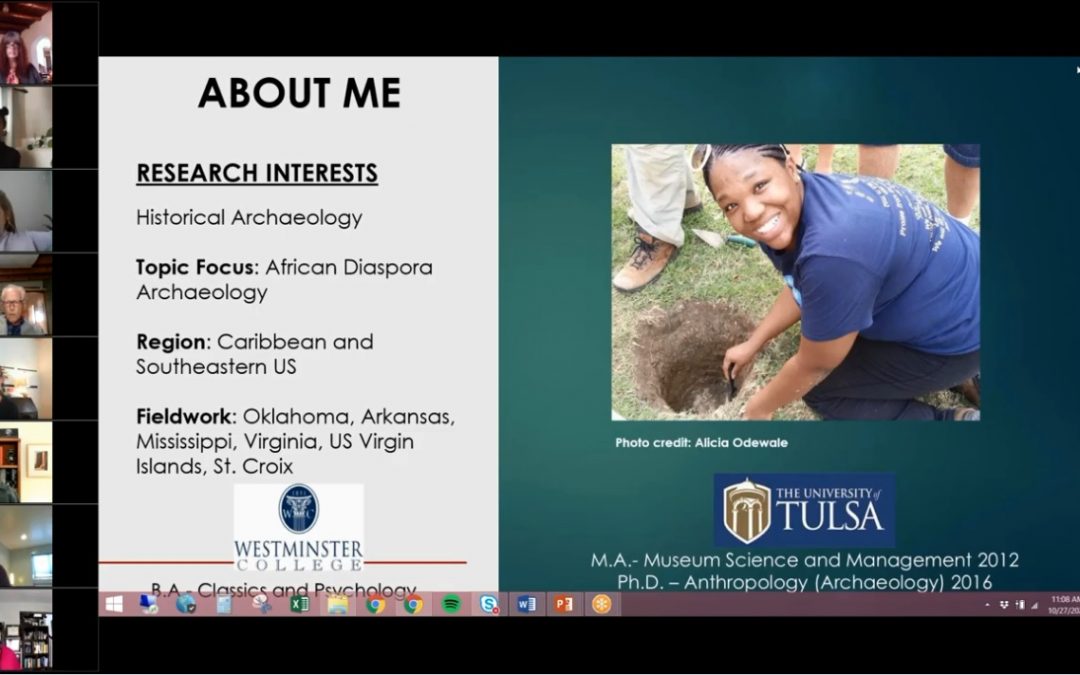

As 2021 marks 100 years since the 1921 attack on Greenwood, Dr. Odewale is committed to a restorative justice approach in her work. She is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Tulsa, specializing in African Diaspora Archaeology with a historical and anthropological framework. A native Tulsan herself, she is the only Black archaeologist working in the city, during an era in which non-Black and non-local outsiders are shifting the narrative about Greenwood. Their reports see Greenwood as a historical event, not a dynamic community that existed pre-statehood and which still remains today; they center their stories on racial violence and Black death, without considering the lived experiences of residents before and after the massacre; and they circle around the search for mass graves, rather than prioritizing community healing and growth.

Through the virtual SAR In-Depth course Unearthing Violence: Archaeology in the Aftermath of the Tulsa Race Massacre, Dr. Odewale reclaimed the conversation. Class one, “Restorative Justice and Community Led Archaeology,” laid the groundwork for a new method of archaeology she’s developing, in which Greenwood community members and descendent families guide the research project. Class two, “Finding Signs of Life in the Massacre,” expanded the discussion by comparing her survey of critical sites of memory with the city’s search for mass graves. Importantly, both sessions spiraled back to the central question: what would a healed Greenwood look like?

Dr. Odewale is involved in two separate projects about Greenwood: one retributive in nature, the other restorative. The retributive project is the City of Tulsa’s search for mass graves, which began in 2019 and has since received nationwide attention and coverage. The number of massacre-associated deaths from 1921 are still unknown: the initial coroner’s report recorded 36 deaths; a 2011 commission report suggested anywhere from 100 to 300; and some contemporary scholars say the count could be in the thousands. Dr. Odewale notes that the Greenwood community does want to locate and document these unmarked graves, and that the city-led search is a step toward justice. But she also makes clear that healing, in the context of Greenwood, means more than closing a homicide case.

Her restorative justice archaeology project has a larger scope, focusing on mapping historical trauma in Tulsa from 1921 through 2021. Unlike the search for mass graves, this work moves through time, place, space, and memory. Restorative justice archaeology, while it looks different for distinct communities, is necessarily multivocal, dialogical, deeply historical, and informal. Dr. Odewale took these tenants and expanded upon them, asserting that in the case of Greenwood the project must also be layered, community-based, and visionary. Currently in the beginning stages of their project, Dr. Odewale and co-leader Parker VanValkenburgh are using the methods of slow archaeology to mindfully collaborate with descendants, educators, activists, and politicians, ultimately prioritizing community needs before research needs.

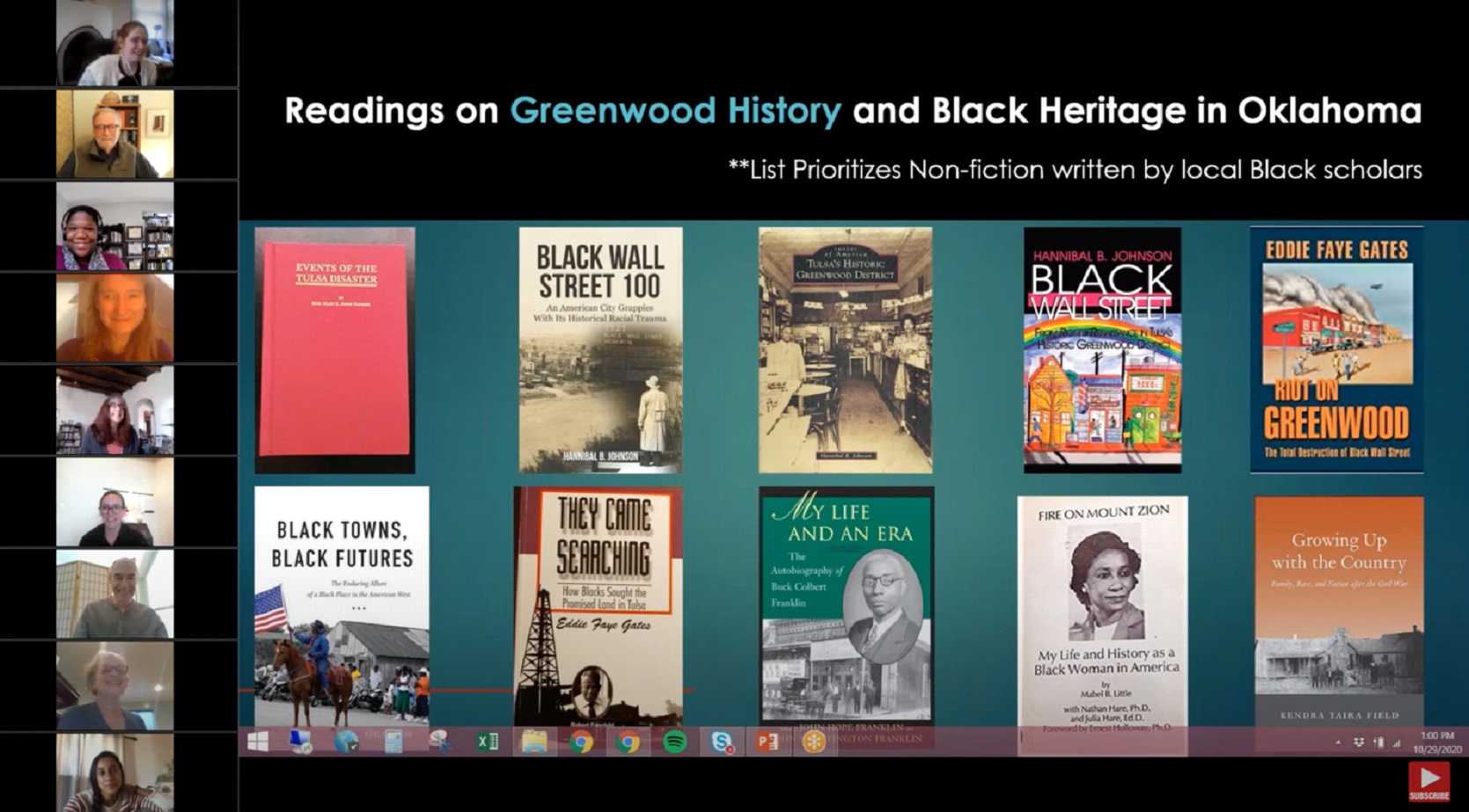

Each section of the project is rooted in healing. The first goal is to locate and inventory every Tulsa Race Massacre collection around the world, as the archival documents have become just as scattered as the details surrounding the 1921 event. This work will culminate in the creation of a Greenwood Centennial Resource Collection, which will be accessible free of charge to the North Tulsa community. The second aspect of the project is to map a footprint of the Historic Greenwood District through WebGIS mapping software, whereby the content – incorporating photos and documents from the Greenwood Collection – will be relational and interconnected.

With phase three, Dr. Odewale is working towards developing critical sites of memory through geophysical survey archaeological excavations. This section of the project is a crucial break from the media’s fixation on Black death and violence, and instead hones in on the larger stories of Black resilience imprinted within Greenwood’s landscape. Finally, the last goal is centered on creating tools for new knowledge production and educational applications. The Tulsa school systems do not yet have a standardized curriculum for teaching about the Tulsa Race Massacre; by developing a broad body of resources, Dr. Odewale will provide youth with multiple access points to connect to Greenwood’s history, so that they can envision Greenwood’s future.

While archaeology is intrinsically tied to the past, this course lays out its implications moving forward, specifically for historically traumatized communities. Dr. Odewale grounds her research in the lived experiences of Greenwood citizens, outlining their moments of vibrancy, dynamism, and resilience through time. Though the search for mass graves has overtaken the headlines, this SAR In-Depth course on restorative justice archaeology shifts the conversation back to the community – prioritizing healing, and hope, for the next Black Wall Street.