Christopher Boehm

Weatherhead Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Director of the Jane Goodall Research Center and Professor of Anthropology

University of Southern California

PROJECT:

The Evolution of Moral Communities

“In a discipline that is experiencing severe rifts between ‘humanists, and ‘scientists,’ I feel that the best way to heal this schism is to produce provocative work that bridges the gap,” says Boehm. During his fellowship year, Boehm is working on a book titled The Evolution of Moral Communities which will combine humanistic and evolutionary approaches to explain a major problem of interest to philosophers, theologians, anthropologists, and biologists: the basis of human altruism.

Boehm’s argument is that the human sociobiologists have missed the main evolutionary process that differentiates human from most other animals, a form of group selection. “Bands regularly promote altruism, and I shall demonstrate that this is explainable in terms of currently neglected mechanisms of natural selection. This will require a departure from standard evolutionary-biology theory of the past three decades, which simply sets aside selection taking place between groups as being irrelevant,” asserts Boehm.

“I believe the book will provide new answers about how hunter-gatherers moralize, about the place of morality in natural history, and about a human nature that probably is more altruistic than presently acknowledged.”

Boehm’s most recent book, Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior was published in 1999 by Harvard University Press and examines the human sense of autonomy and freedom in an evolutionary context. With David Sloan Wilson, Boehm is conducting an ongoing research project, supported by the Templeton Foundation, that focuses on explaining conflict resolution and forgiveness behavior in an evolutionary context.

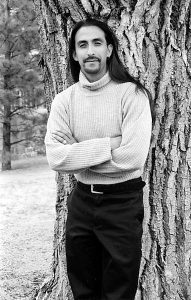

Estévan Rael-Galvéz

Estévan Rael-Galvéz

Katrin H. Lamon Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Ph.D. Candidate

Program in American Cultures

University of Michigan

PROJECT:

Identifying Captivities and Capturing Identities: The Contest of Stories and Memories in the American Indian Captivity and Servitude of Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado

Rael-Galvéz was able to trace Luis and his descendants from an Indian Agent’s 1865 inventory of Indian captives, to a 1934 encounter with a U.S. Civil Works Administration agent, to a recent interview in Denver, Colorado. Having lived within the Valdez family all of his life, Luis embodies the plight of the “criado” or “servant” held captive yet treated “like family” over generations: while “Indian slavery” was officially illegal throughout all three periods of occupation in this region, the lived experience of servitude calls this “age-old custom” into question.”

“My goal is to examine indigenous captivity and servitude as experience, as a contest of stories, and as memory,” explains Rael-Galvéz. “Tracing the experience and story of even a few of those thousands of captured indios means attempting to account for the particular ways in which multiple subjectivities race, caste, gender, nation, and even between the centrally imagined dichotomy of ‘savaged’ and ‘saved’ mark one’s relation toward this reality.”

His investigation will include an analysis of the concept of slavery, as well as the impact of Indian captivity on the collective cultures of the Hispanic communities of the interconnected valleys of Española, Taos, and San Luis, where the largest number of captivities occurred.

John A. Ware

National Endowment for the Humanities Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Project Director

Office of Archaeological Studies

Museum of New Mexico

PROJECT:

Archaeology, Historical Ethnography, and Pueblo Social History

This divergence is reflected in the way the pueblos are organized: While Western Pueblos are governed by ritual groups embedded within kinship organizations, the Eastern Pueblos departed from this pattern at some point and developed ritual groups that not only function independently from kinship control but have emerged as political entities exerting considerable influence beyond the ritual life of the community.

Half a century ago, Fred Eggan, the dean of Pueblo ethnographers, put forward a model explaining these differences, locating the time of the divergence at around the fourteenth century. Eggan’s theory of when and why this happened centers around population dislocations, economic specialization, and Euroamerican acculturation in the Rio Grande Valley. National Endowment for the Humanities Resident Scholar John Ware is challenging Eggan’s model, and creating an alternative theory that employs an unusual approach to unraveling these Pueblo mysteries.

“While Eggan was probably right that the Eastern Pueblo organizations are derived from the Western matrilineal clan groups, he is almost certainly wrong about the timing of the east-west divergence,” says Ware, who argues that the separation occurred not in the fourteenth but the eighth century, and involved the detachment of the ritual sodalities or groups, from the parent kinship institutions. His book, Archaeology, Historical Ethnography, and Pueblo Social History (co-authored with Eric Blinman, forthcoming), presents a detailed narrative about how and why these changes occurred.

One factor that distinguishes Ware’s model of Pueblo social history is the use of the present as a destination point. “This approach is very controversial,” Ware states. “Most scholars working in archaeology and prehistory have come to the conclusion that the historic pueblos have been disconnected from their pre-historic past. They feel that this destination was so changed by the historic period, especially the arrival of the Spanish, that it really bears no resemblance to what those pueblos were like before the Spanish presence. From this perspective, to use the modern pueblo as a destination would give the scholar a totally skewed picture of what the process was.”

Ware intends to demonstrate that this disconnection is not real. “If you’re taking a road trip from Santa Fe to Los Angeles,” Ware contends, “it makes more sense to go through Flagstaff than through Seattle. When trying to reconstruct a trajectory, considering the destination is important.” Ware points out that there is a lot of continuity between past and present pueblos, in social institutions especially, and therefore “to ignore the ethnographic present is a huge mistake.”

Beyond the specifics of Pueblo social history, the broader aspects of Ware’s research have to do with multiple pathways to social complexity. “Mapping these changes,” Ware believes, “will have implications beyond the borders of the northern Southwest.”

Kent G. Lightfoot

Weatherhead Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Professor of Anthropology

University of California, Berkeley

PROJECT:

California Frontiers: The Ethnogenesis of a Pluralistic State

While the Hispanic missions were concerned with converting the Native peoples to Catholicism and integrating them into Spanish culture, the Russian mercantile colonies, such as Ft. Ross, were focused primarily on generating profit as long as the Native peoples remained peaceful and didn’t disrupt labor practices, they were allowed to maintain their own cultures.

This essential contrast resulted in dramatically different impacts on the many small hunter-gatherer tribes of coastal California, caught between these two colonial systems: Groups such as the Kashaya Pomo, who interacted with the Russian system, were generally able to retain their tribal identities; most of the Southern California native groups, who encountered the Hispanic mission system, became fragmented and underwent significant cultural change.

Unlike most histories of colonial California, California Frontiers focuses explicitly on interactions between Natives and colonists, and explores new ways of using multiple data sources such as ethnohistory, Native oral traditions, and perhaps most significantly archaeology.

“Archaeologists view their field as a viable source for examining the life ways and interactions of poorly documented peoples in the past,” Lightfoot explains. “If archaeology can truly ‘democratize’ the past, then California is ripe with promise for rewriting history given the massive amount of archaeology that has been undertaken in the state in the last twenty-five years.”

Patricia Marks Greenfield

National Endowment for the Humanities Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Professor of Psychology

University of California, Los Angeles

PROJECT:

Weaving Patterns: Ontogenetic Constraint and Cultural Construction in the Creative Process

When Greenfield returned to Zinacantan in 1991, she found that the learning process had shifted to a more trial-and-error, discovery-oriented one, often directed by an older sister rather than the mother, and that there were changes in the fabrics, as well. “I found an infinite array of textile patterns,” Greenfield says. “Individual uniqueness and self-expression—what some Western theorists call creativity—had arrived in Zinacantan.” Why did this happen? During the twenty-one year interim between Greenfield’s research visits, the village had undergone a transition from agricultural subsistence to an entrepreneurial cash economy. She predicted that this shift would have significant effects not only on the way weaving is taught, but also on fabric design and variation. “The idea is that when you have entrepreneurship, novelty and innovation become important. Also, in a commercial, money-based economy, people become more independent,” and women are less restricted to work in the home, says Greenfield.

Drawing on a unique set of data involving two generations of mothers and children, Greenfield documented dramatic shifts in the learning process. “I’m really studying the changes in models of creativity that happen as a result of economic development,” she explains. Greenfield’s project, Weaving Patterns: Onotogenetic Constraint and Cultural Construction in the Creative Process, explores weaving apprenticeship, pattern representation, and textile design over two time scales: individual development and historical change. The resulting book, accessible to a popular audience, will be generously illustrated with color photographs taken for National Geographic by Greenfield’s daughter, Lauren.

Paul Nadasdy

Weatherhead Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Ph.D. Candidate

Department of Anthropology

The Johns Hopkins University

PROJECT:

The Politics of 'Traditional Knowledge: Power and the Integration of Knowledge Systems in the Yukon Territory, Canada

“The idea of integration contains the implicit assumption that the cultural beliefs and practices referred to as ‘traditional knowledge’ conform to western conceptions of knowledge,” Nadasdy states. His dissertation, “The Politics of ‘Traditional Knowledge’: Power and the Integration of Knowledge Systems in the Yukon Territory, Canada,” is drawn from thirty-two months of fieldwork in the Yukon’s southwest corner in Burwash Landing, a village of about seventy people, most of whom are members of the Kluane First Nation. Nadasdy participated in the daily life of the community, such as trapping and hunting, and accompanied teams of villagers and local scientists to gather information about environmental concerns, such as the diminishing population of big-horned sheep.

“My fieldwork provided me with an understanding of the social relations, values, and practices in which local ‘environmental knowledge’ is embedded,” says Nadasdy. Without such understanding, he asserts, the governmental agencies addressing land issues and concerns can misconstrue traditional knowledge or even dismiss it as being irrelevant.

To focus on how people in political arenas actually use “environmental knowledge,” Nadasdy examined a number of local political struggles, including case studies drawn from resource management, aboriginal land claim negotiations, and local environmental politics. “I show how the process of integrating TEK and science takes place in a political context, and further, that there are practical difficulties involved in translating native beliefs and practices into forms that are understandable and acceptable to non-natives-even those who have explicitly stated their willingness to ‘use TEK,'” explains Nadasdy.

Nadasdy concedes that great effort and expense have gone into trying to understand and document TEK in the circumpolar north as part of the co-management initiatives between government and indigenous peoples. However, by treating TEK as “just another form of data,” these efforts ignore what the holders of this knowledge universally claim to be its most important feature: its integration into a whole way of life. “I am hopeful this project will be useful to scholars and aboriginal people throughout the world who are concerned with indigenous-state relations and local knowledge,” says Nadasdy.

Susan E. Ramirez

National Endowment for the Humanities Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Professor of Latin American History

DePaul University

PROJECT:

To Feed and Be Fed: Legitimacy and Cosmology in the Andes

The Incan empire was not organized as a constantly-expanding economic territory or somehow patterned after the human body, as the prevailing models of the last few decades hypothesize. Ramirez contends that Andean cosmology including multi-tiered ritual, folk religion, and ancestor worship provided an ideological underpinning of rulership and society at both the Inca and provincial levels.

This new perspective on the link between Andean political power and cosmology began to surface for Ramirez as she read general empire-wide accounts written by the chroniclers of the 16th and 17th centuries, after years of working in provincial archives with more localized documents. Certain inconsistencies led her to suspect that a fundamental presumption about the Incan empire was incorrect.

Based on the chroniclers’ reports, “the empire had always been portrayed as a territorial empire with a geographic center, a ‘capital’ like Washington, D.C.,” explains Ramirez. The Spanish accounts put everything they saw and didn’t understand into their own cultural mold so the huge Andean empire was mistakenly assumed to be organized like a European one. But this wasn’t the Andean way at all. The empire’s center, or the “navel of the universe,” was a person, not a place. The empire was hegemonic, based on authority, not territory. It did not have fixed boundaries. Further, the Incans had no merchants, no markets, and no money. The Andeans were a non-western peoples with a different kind of society and culture.

This pivotal shift led Ramirez to document the significant role of religious beliefs, sacrifice, divination, magic, and ritual in ordering traditional Incan society. More broadly, she examines and illustrates the problems of describing and understanding a non-western society using sources written with heavy western biases and in a European language. “Basically what I’m trying to do,” Ramirez says, “is to be a political scientist for the Incas. I want to explain what allowed them to create and hold together this huge empire made up of hundreds of small ethnicities.”