White Paper “Aging in Place: Challenges and Prospects”

Prepared by Jessica C. Robbins, Annette Leibing, Aaron T. Seaman, and Agnes Vallejos

“Aging in place” is a common phrase meaning that older people prefer to age (most frequently through the end of their lives) in their homes, in spaces that represent their lives, and ideally close to family and friends. The World Health Organization (WHO 2015, 36) states that aging in place is “the ability of older people to live in their own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income or level of intrinsic capacity. This is generally viewed as better for the older person and may also hold significant financial advantages in terms of health-care expenditure” (see also Wiles et al. 2012; Leibing, Guberman, and Wiles 2015). However, many factors can influence a person’s desire to age in place and the feasibility of such a project. Contextual factors, such as health issues, social network, and income, can negatively shape a person’s ability to age in place, rendering this experience isolating and insecure. Also, aging in place is generally based on a deeply individualistic idea of living space and does not represent the desire of all people; in some cultures, community spaces or intergenerational living spaces are preferred choices. Therefore, aging in place does not necessarily mean only an individual living space, like a house or an apartment: a group living project can become home or may have always been home, as it can be linked to a wider notion of neighborhood or country, as in (home)land.

This white paper is the result of a salon held at the School for Advanced Research (SAR) that took place on June 6, 2019, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which was generously sponsored by the Ethel-Jane Westfeldt Bunting Foundation.

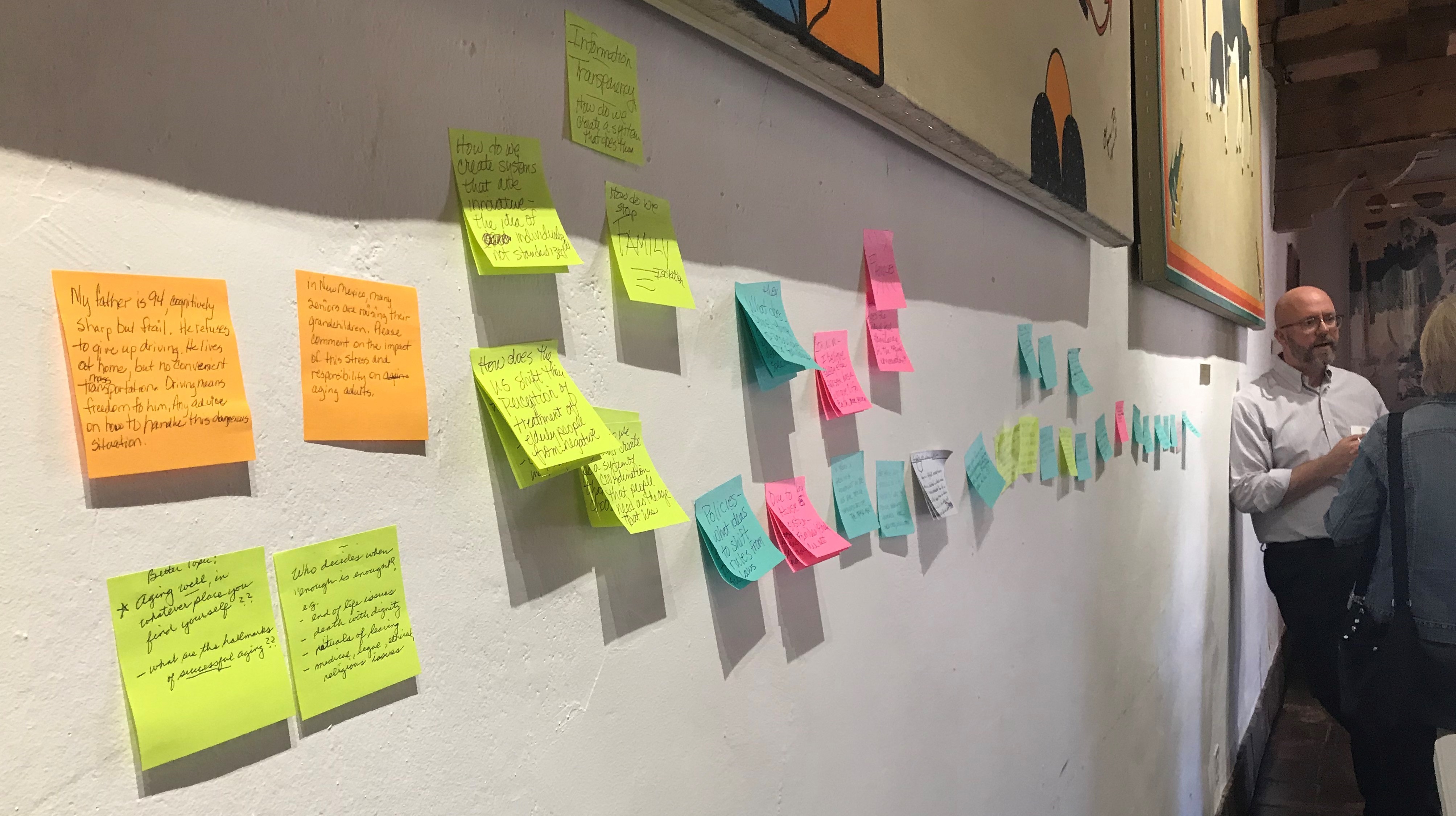

The salon was organized by three anthropologists who work on different aspects of aging (Robbins, Leibing, and Seaman) and one social services manager who works with older people in New Mexico (Vallejos). The day-long event comprised morning and afternoon sessions. In the morning, the four speakers began with a short presentation intended to deepen the discussion on aging in place by each focusing on one central concept: liminality, coordination, place, and the Older Americans Act. Each concept challenged assumptions about aging in place. Presentations were followed by a question-and-answer period. The speakers also invited the audience to write down questions on pieces of paper that were then collected and organized to guide the afternoon’s discussion. Audience questions clustered around three major topics: (1) how to practically prepare for aging in place, (2) the role of the family, and (3) how to enact change.

The sections below provide an overview of the arguments made by the four speakers, along with a summary of the questions and preoccupations of the audience.

We hope to be able to provide some data for an interested readership starting to think about the important issue of where and how to age.

Liminal Homes: Older People and the Present Future of Living Spaces / Annette Leibing

Annette Leibing

The first paper, given by medical anthropologist Annette Leibing, introduced the notion of “liminality” into the discussion on aging in place. Liminality is an in-between state, when the known (e.g., the home) is threatened and loses its taken-for-granted status in daily life. In the social sciences, this notion goes back to Arnold Van Gennep (2004 [1960]) and Victor Turner (1969), who linked liminality to another idea: rites de passage. These are commonly accepted rituals, such as a wedding ceremony that marks a person’s passage from unmarried to married, with well-defined expectations regarding the way the transformation, as well as the new state of being, should be experienced. In many societies, however, such rituals have lost their force, so that liminality is more often experienced individually and less likely framed by the social order. In the case of liminality due to decline in old age, different kinds of help need to be mobilized, including that of families, neighbors, and the state, often without a guarantee that all needs will be met.

Not all older people experience such declines in autonomy—autonomy being an important Western value—yet a great number of seniors are affected. Karen Bandeen-Roche and colleagues (2015) found in their US study that 60 percent of older people (65+ years) living in the community were frail and what the authors call “pre-frail,” although with stark regional differences. All of these people will probably need some help sooner or later in order to manage daily living, and their present living arrangements will need to be adapted or, in more severe cases, abandoned.

In order to show what is at stake when people live in “liminal homes,” Leibing presented some data from the Montreal study on aging in place (e.g., Leibing, Guberman, and Wiles 2015). The study is based on interviews (and photo-elicitation)[1] with twenty-six older people who had limited financial resources (and therefore less potential to compensate for different kinds of losses) and who needed help with health issues to the point that they were at least thinking about moving.

Some of what came out of the study is well known in the literature; for instance, the importance of home as a site of intimacy and identity (the image of “pajamas” was often used, e.g., “Here I can be myself and stay the whole morning in my pajamas and no one judges me”). Specific objects that represent one’s life—from photos of family members to inherited objects—appeared in the interviews and are well described in the literature. “Activities” of different sorts were also important. Photos showed interviewees engaged in social activities (like playing cards) and individual activities (like reading the newspaper in a favorite armchair or exercising), as well as spending time at well-liked places in the neighborhood, which linked the idea of home to the community. Images of visitors, friendly neighbors, parks, and nearby shops can all be found in the photos taken by the seniors.

Regarding the concept of liminality, the manifold ways people talked about home, and conceived of it in opposition to a feared institution, were especially interesting:

There [in a nursing home] one doesn’t see animals, nor children. Everybody is old. . . . Better stay in our homes, because our brain doesn’t get clouded with only seeing sick people, people who do not function anymore. . . . I’d rather they kill me than to move there, because there are not really older people there, not really persons. (LB07)[2]

There the only things you hear people talk about are medications, diseases, and suicide! (NG2)

However, the home, the antithesis of the institution, also gets transformed into a site that might become the feared institution. Choice and autonomy experienced at home are diminished by the adaptation of one’s home (e.g., by having a hospital bed installed) and by incoming home care—even when family members provide needed help. In short, the hominess of home can be lost.

It’s hard to accept, it’s not easy. The people who come are not always pleasant and they change all the time. I am a vegetarian and had to explain this again and again. . . . I had to fight to always get the same person; they change all the time. . . . I wouldn’t like to get more help, I have enough; I prefer doing it slowly, at my rhythm, than having too many people in my home. I hope there won’t be eventualities, that I will have to . . . (LEH1)

And even when older people would like to move, the institutions available to poorer people are rarely pleasant places and so discourage action. In this sense, people who need help but cannot afford a pleasant environment get “stuck in place” (Sharkey 2013; Lehning et al. 2015).

Finally, interviewees were constantly “fighting liminality,” in the sense that they emphasized the positive qualities of their homes, even idealized their homes, sometimes despite inadequate conditions. A woman with severe mobility problems in a three-story house said,

Oh no no no [problem]. It’s actually . . . it’s good to take some exercise, it’s not many stairs, it’s OK, it’s fine. But it’s like I said—the government, they don’t care much for the people who used to work for Canada many, many years—me and my husband, we never stop working! (AL1)

Several interviewees described the support they had as a patchwork of family, friends, volunteers, privately paid workers, and state care, on which they could not always rely. For instance, LB5, a ninety-year-old woman who lives in her own apartment and who recently had a stroke, suffered from cataracts, heart problems, musculo-skeletal problems, and reduced mobility. She counted on her daughter’s visits three times a week for some cleaning, twice weekly visits from the local CLSC[3] (which offers the public free home-care programs) for bathing, occasional visits from a woman she hires for cleaning, and visits from volunteers, primarily for conversation. LB1 explained her “patchwork of care” with the following words:

There is Josée for my stockings, there is Daniel or what was his name? He only came twice. . . . He does the cleaning. There is Catherine, she came today, yes, and Daniel comes the weekends. I had asked him to change his schedule but he could not, and I told Josée that on Sunday I wanted to attend church, but she has other obligations. . . . I try to be kind and not ask too much. (LB1)

What can we learn from these interviews with people living in liminal housing? Turner (1969) associated liminality with social invisibility and a lack of classification (no longer classified and not yet classified again). We might say—and this despite the fact that several of the interviewees enjoyed life even with severe limitations—that these senior persons are the most invisible people, they are “in-between citizens.” And because of this, their patchwork arrangements for maintaining a home are especially difficult to sustain. They are older people who are neither part of the group of active and independent “model” seniors (those who are “actively aging”), nor totally dependent people who sometimes live under terrible conditions but are nonetheless discussed as people in need. People in liminal living arrangements are rarely included in social policies or social movements. In order that institutions like nursing homes become desirable to those who need them, they need to provide autonomy, privacy, and choice for those who valorize these values, like the interviewees in the Montreal study. And as long as older people want to live at home, needed care should be a right and a priority of governments, so that liminality vanishes—a seeming utopia that is actually entirely possible in many societies.

[1] Each interviewee was given a simple camera with which to take pictures of their “idea of home.” The pictures were used for follow-up interviews that used the images to introduce topics not covered in the first interviews.

[2] Parenthetical identifiers are used to maintain research participants’ anonymity.

[3] CLSCs (centre local de services communautaires, local community service center) in Quebec are free clinics run and maintained by the provincial government. They are a form of community health center.

Coordination / Aaron T. Seaman

Aaron T. Seaman

Coordination, the concept that medical anthropologist and health services researcher Aaron Seaman introduced in his talk, focuses attention on two related facets of aging in place, especially within the United States, where he conducts research on care and uncertainty among older adults. The first facet is that the project of aging in place—of, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines it, a person’s “ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level” (https://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/terminology.htm)—involves multiple components. We see this even in the CDC’s definition with its references to people, homes, communities, aging bodies, financial concerns, and questions of ability, safety, independence, and comfort, all of which implicate a range of bodily, social, and material relations. The second is that holding all these often-disparate components that compose “a person” together coherently requires work: specifically, it requires coordination.

Anthropology has long been suspicious of the idea that people are intrinsically independent and coherent beings, what Clifford Geertz (1983, 59) referred to as that “peculiar” “Western conception of the person.” Elana Buch (2018, 19) writes in her book on home-care workers and older adults in Chicago that independence is “a normative category rather than a descriptive one.” She describes it thusly in order to point out that independence is far from an actual, achievable state of being-in-the-world; rather, it is an aspiration of moral imagination, a state of being-in-the-world that people in the United States value and, because they value it, use to understand themselves and make sense of the world around them. As Buch writes,

Despite Americans’ emphasis on independent living, people of every age and ability profoundly rely on others. We rely on other beings—both human and non-human—in every aspect of life, from those activities necessary for our survival to those that form the foundation of our ways of life. Older adults’ independence comes into question not because they are more reliant on others than those of other ages, but because their interdependencies are more visible. (Buch 2018, 19; see also Kittay 1999)

Along with independence, people in the United States value a coherence, or continuity, of self across both time and place. Yet this, too, is illusory, a product of narrative (and other) work. As Athena McLean (2006, 171) in her work on dementia explains, “Although distinct selves are created in response to the demands of new life contexts, an illusory experience of wholeness, coherence, or ‘unity of feeling’ is achieved because each self-representation organizes fragments of experiences as if they were constant and timeless.” She reminds us that “coherence is a symbolic process” more dependent on whether we feel coherent than any actual continuity across history. This fragmentation makes sense if we think about, for example, people who are described as good at “compartmentalizing” the different aspects of their lives—work, family, friends, and so forth. As with independence, though, people tend to be discomfited by their own lack of coherence and therefore strive to pull it all together in a single meaningful self-narrative.

Pulling aside the curtain on independence and coherence, we can start to discuss the person who is aging in place from a slightly different vantage point. This notion of interdependence that Buch introduced—that we are all deeply connected with and reliant upon others—is useful here as it highlights the connections—the relations—between the person and the bodily, social, and material entities with which they interact. An interdependent person sits at the center of a web of such relations (Heinemann 2016), which we might categorize in this way:

The work to hold the pieces of this interdependent whole together is what Seaman refers to as coordination. Importantly, coordination shifts our attention from what something is to what something does. It highlights the fact that the appearance of a coherent, independent person is a product of work, of practices. “If practices are foregrounded,” writes Annemarie Mol (2002, 5), “there is no longer a single passive object in the middle, waiting to be seen from the point of view of seemingly endless series of perspectives. Instead, objects come into being—and disappear—with the practices in which they are manipulated” (see also Thompson 2005). By shifting our gaze to the coordinating work of coherence as people age and strive to do so in the midst of a body, home, and world that are always changing, we can not only see the many components and actors involved in aging, but also perhaps differently envision the challenges and possibilities of an emplaced aging.

Place / Jessica Robbins

Jessica C. Robbins

What do we mean by the “place” of aging in place? Although the phrase “aging in place” emerged precisely to specify the home as opposed to an institution, anthropologist Jessica Robbins suggested in her presentation that a broader consideration of the relationships between persons and places can help us to reimagine what aging in place could mean. To do so, she drew on examples from ethnographic research among older adults in Poland and in Detroit and Flint, Michigan.[1]

Historically, aging in place emerged in response to the prevalence of institutional care, and especially poor institutional care. This has led to a focus on the place of residence over other kinds of places. Although our relationships to physical and social components of a place of residence are indeed central to experiences of aging, it is also true that not only the physical place matters. We also have relationships to the places that these residences are in: neighborhoods, cities, regions, states, nations. The focus on the home in conversations about aging in place leads us to emphasize the meaningful aspects of our homes as bound up within the apartment or house—that is, within the physical place itself—but elements of the broader community also contribute to the physical elements of place. For older adults in Flint, Michigan, for instance, the fact that the state made decisions that led to the contamination of municipal drinking water with lead and other toxins has shaped how older adults understand and experience the city in which they live.

Our experience of place can also include remembrances and imaginations. One woman Robbins knew in Poland lived at home with her daughter, son-in-law, and grandson in the city of Wrocław, which for approximately eight hundred years before the end of World War II had been the city of Breslau, occupied primarily by ethnic Germans. In 1945 the city became part of postwar Poland. A retired physical therapist, now widowed, this woman lived on the ground floor of a house built in the early twentieth century that she and her husband moved into after World War II. Conversations went on for hours as she told the story of her life, interwoven with that of the Polish nation (Robbins 2013). Pulling out files of photos from their location under the bench in her room, she showed Robbins pictures of nameless ancestors in Galicia, territory that is now part of Ukraine but before World War II was part of Poland. This region is beloved and lamented by older Poles, especially in Wrocław, a city to which many from Galicia moved after the war. All of which is to say that even while in her own residence, she showed how the imagined territory of Galicia continued to matter as part of the historical Polish nation.

- Key question posed by the author: How might including remembered and imagined places in the “place” of aging in place shift our understanding of the concept and provide new opportunities for creating good years later in life?

In Detroit and Flint, aging in place takes on new meanings for older adults whose home values have catastrophically fallen due to contemporary transformations in these cities. In the last decade, both cities have experienced a dramatic loss of property value, which has had a particularly negative impact on people of color. Older adults in such situations come to be “stuck” in place; in other words, they would like to move but are not able to do so. In Detroit, high property tax rates have not fallen with property values, which means mean that people have been foreclosed on because they have not been able to pay taxes even when they have paid off the houses themselves. In Flint, the water crisis has decimated property values, forcing people to stay even if they might want to leave. In both cities, many live in poor quality housing stock. These problems have become so severe that some research participants do indeed want to leave their homes and their city, which they love and have lived in for decades. Others prefer to stay, while still others express conflicted sentiments. However, these cities and homes have become so transformed, and in part through histories of racialized inequality, that aspirations for aging well have been thwarted.

- Key question posed by the author: In which kinds of places do people aspire to age, and for whom is it possible to achieve these aspirations? How are these forms of inclusion and exclusion linked to other kinds of social inequality?

Robbins encourages us to think about aging in place as not only about the physical place in which we are aging. How can we age well at home, among kin, and on our own terms? What possibilities for aging well exist at home or elsewhere? Asking such expansive questions could help to shape policy such that our ideals might become more aligned with existing realities.

[1] The study in Flint, Michigan, is a collaborative project with Tam Perry, an anthropologist and scholar of social work.

The Aging in New Mexico / Agnes Vallejos

Agnes Vallejos

New Mexico is often touted as a great place to retire because of its natural beauty, temperate weather, and relative affordability compared to states like California and Texas. Typically, retirees who have moved to New Mexico have retirement income that allows them more options in how they age in place. But for many older New Mexicans, remaining in their homes might be their only option.

In the past few decades, very few new nursing home facilities have been built in New Mexico. If someone desired to move into a nursing home, they would face limited bed space. Independent living and assisted living facilities have proliferated in many, mostly urban, parts of the state, but the cost of these facilities is prohibitive to many older adults whose only income is often Social Security.

For those New Mexicans who are aging in their communities, the aging network in New Mexico is critical to providing them with the supportive services they need to remain as independent as possible, for as long as possible. This network of federal, state, and local agencies was established through the Older Americans Act of 1965, which was the focus of social services manager Agnes Vallejos’s talk.

Older Americans Act

As part of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society reforms, three programs important to older adults and their families were enacted in 1965: Medicare, Medicaid, and the Older American Act (OAA). Familiar to many, Medicare and Medicaid are health-care insurance programs designed to provide a safety net to the elderly and the poor, respectively. The lesser known OAA also provides a safety net to older adults and adults living with disabilities by funding community-based services designed to help them live in their homes and communities as long and as independently as possible. The OAA contains targeting language that focuses assistance to persons aged sixty and older with the greatest social or economic need, such as low-income or minority persons, older individuals with limited English proficiency, and older persons residing in rural areas. The OAA also supports families of older adults by offering services to unpaid caregivers. Additionally, the OAA provides funding to encourage the development of jobs in the health and long-term care sectors in local communities around the country.

The OAA consists of seven titles. Titles I and II declare the act’s objectives and establish the Administration on Aging (AoA), the federal coordinating agency for OAA services. Title III of the OAA establishes Grants for State and Community Programs on Aging. Title III authorizes the funding for most of the community-based programs designed to support older adults and those living with disabilities in their communities. These supportive services include senior center services that combat social isolation and loneliness, both of which can have a negative impact on health; information and referral services; case management; and in-home services such as homemaker, respite, chore, and medication management. Transportation services are also funded by Title III. These transportation services can include, for example, rides to and from senior centers, grocery stores, and the post office. Assisted transportation services provide not only a ride to appointments, but also someone to accompany the older or disabled person. Over 40 percent of federal spending through the OAA is on nutrition programs such as home-delivered meals and congregate meals at senior centers. Included in Title III of the OAA are family caregiver support and evidence-based health promotion and disease prevention services. In New Mexico some of these programs include fall prevention programs, Managing My Chronic Disease programs, and caregiver training programs.

Title IV of the OAA provides support for training, research, and demonstration projects, and Title V authorizes the Senior Community Service Employment Program. This program is managed by the Department of Labor, whereas additional senior employment programs are funded by the New Mexico legislature through the Aging and Long Term Services Department (ALTSD). Both of these programs provide support for job training through part-time employment for low-income older adults.

Title VI covers grants for Services for Native Americans and provides funding to tribal organizations, Native Alaskan organizations, and nonprofits representing Native Hawaiians.

Title VII provides support for programs to ensure protection of the rights of older adults, including the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program (LTCOP) and elder abuse prevention services. The LTCOP is required to investigate and resolve complaints made by or on behalf of nursing facility residents or other institutionalized populations.

How the Money Flows to Providers

The OAA is beautifully and intentionally designed to meet the needs of the local community. While initially the federal government controlled the funding provided by the OAA, in the 1970s states began to develop Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs) to better serve local communities. Presently, federal funding flows from the AoA to the State Unit on Aging. In New Mexico, ALTSD is the recognized State Unit on Aging and is responsible for developing a funding formula for federal dollars based on population and rural factors and for establishing Planning and Service Areas (PSAs). Additionally, ALTSD allocates state funding for aging programs and capital projects authorized by the New Mexico Legislature.

In New Mexico, six Planning and Service areas are served by four AAAs. These AAAs include Bernalillo County / City of Albuquerque (PSA 1), Non-Metro Area Agency on Aging (PSAs 2, 3, and 4), Navajo Area Agency on Aging (PSA 5), and Indian Area Agency on Aging (PSA 6). Each AAA develops a four-year Area Plan to address the needs of older adults in their respective PSA. AAAs have the flexibility to ensure local needs and preferences of older adults are taken into consideration. The AAAs also leverage funding provided by local municipalities.

Challenges

In New Mexico there exists a disparity between urban and rural communities. Rural New Mexico is “aging” due to a lack of economic opportunities for young people, who often relocate to larger cities in New Mexico or out of the state. Rural New Mexico provides fewer services, especially health-care providers and medical specialists. For many older adults, their only choice is to remain in their community even though they lack the services they need. Counties are mandated to provide emergency services and law enforcement but are not required to provide services to older Americans. This leaves poorer communities with very limited services for older adults.

New Mexico is well known for its wide open spaces; indeed, many parts of the state are designated as frontier (less than seven people per square mile). New Mexico is the fifth largest state by area but thirty-seventh by population. The vastness of the state combined with the lack of local services makes transportation an even larger challenge. Many communities lack essential services such as grocery stores, and people living in those communities often must travel fifty or sixty miles to buy groceries.

In addition, New Mexico ranks eighth in the United States in food insecurity. For many of the older adults served by the OAA-funded programs, a congregate or home-delivered meal may be their only hot meal of the day. In some areas, delivering a hot meal every day is not possible, so the local programs may provide one hot meal and five or six frozen meals to clients.

As the population ages, caregiving becomes increasingly important and needed. In New Mexico over 419,000 family caregivers provide more than 274 million hours of unpaid family care that is estimated to value $3.1 billion annually. Family caregivers experience myriad burdens such as a negative economic and health impacts. Caregiving responsibilities often fall to women, who then experience depressed earning potential.

Looking to the Future

New Mexico will become the fourth oldest state by population in 2030. There will be more people over the age of sixty-five than under the age of eighteen. Ninety percent of adults age sixty-five and older say they hope to remain in their homes for as long as possible. Programs funded by the OAA have been shown to help people remain at home, but the growth in the older adult population is outpacing the funding provided by the OAA. Aging is now a $14 billion industry and we know that the baby boom generation has always had an impact on what kind of services and products are developed to meet their needs and desires. It will take strong advocacy and creativity now to be prepared for this demographic shift.

Contributions from SAR Salon Attendees

The afternoon consisted of a lively and wide-ranging discussion. In the morning, audience members were given sticky notes and asked to jot down questions or comments as they arose. Before lunch, people placed these notes on the wall of the seminar room. Following lunch, the presenters read through all comments and identified three categories of questions that emerged from everyone’s contributions. These categories were (1) practical questions about resources, (2) questions related to family, and (3) questions about how to enact change. There was an additional category of definitional and clarification questions that, for the sake of coherence in this brief document, we will not include here. In what follows, we have tried to document both the frequently asked questions and the broad range of issues raised.

Resources

Many audience members had practical questions about resources for overcoming challenges of aging in place. People voiced concern related to coordinating the patchwork of care, finding qualified and skilled home-care workers, identifying resources for physical modifications to the home to support aging in place (e.g., grab bars in showers), the availability of therapy animals for older adults, and the quality of independent-living facilities when aging in place is not an option.

Some asked questions drawn from personal experience related to aging in place. A common question was how to age in place in a region (like much of New Mexico) without adequate mass transit. One person wondered how to have difficult conversations with a parent who refuses to give up driving but is unsafe behind the wheel.

Finally, audience members raised the issue of guardianship. Some noted a lack of trust in the state among some older adults and their families due to histories of abuse. Such mistrust can lead to avoiding services that could be helpful for fear of being put into guardianship. Others commented on the contemporary corporate guardianship crisis in New Mexico that they have seen to harm older adults and their families and that, in particular, can disempower family from decision-making capabilities.

Please see Agnes Vallejos’s contribution to this white paper or contact your local Area Agency on Aging for answers to these and other questions.

Family

The topic of family relationships permeated the day’s conversations. Audience members noted the obligations of kin to care for older adults who age in place, and several people raised the question of effects on adult children and spouses of older adults who age in place. It is certainly the case—as was made clear in an example shared by Aaron Seaman about a wife who cared for her husband with dementia with extraordinary creativity, sensitivity, and grace—that not all people are equally able to serve as caregivers for their kin, whether for reasons of cost, ability, or personality. One audience member noted the challenge that can be posed to aging in place when such a skilled family member is absent. Another audience member raised the issue of decision-making in the context of dementia, wondering how much is fair to ask of one’s family members.

Several audience members commented that many families in New Mexico live in intergenerational homes, such that grandparents are raising grandchildren, and asked what the effects of such care on older adults may be. Others wondered if this phenomenon was growing or if there are particular regions of the United States where this situation is more common. Significant anthropological research exists on grandparent/grandchild care, both in the United States and elsewhere, such as that by Ellen Block and Will McGrath (2019), Parin Dossa and Cati Coe (2016), Fayana Richards (2018), and Kristin Yarris (2017).

Change

Given the challenges presented by aging in place, many audience members shared a desire to improve the conditions for older adults who would like to age in place. Moreover, many expressed interest in improving experiences of aging in general, not only for older adults who age in place. People want innovative systems that can account for individual preferences and promote autonomy, provide information in transparent and accessible ways, provide needed support while protecting privacy, and prepare people earlier in life for the necessary “coordination” that late life entails. Audience members and panelists stressed structural factors—notably the fragmented, often lacking, social service provisions for older adults in the United States.

Finally, many audience members commented on social perceptions and stereotypes of old age. Some urged society to shift away from negative stereotypes of old age in which older people seem to lack value and toward a perspective in which older adults can be recognized for their “unique gifts, knowledge, contributions, and abilities.”

The audience posed wide-ranging questions addressing issues related not only to aging in place, but also to aging in general. These issues speak to the complexity of the part of the life course that we call old age, the challenges posed by human frailty in contemporary society, the insights of an anthropological approach, and the need for pragmatic, context-specific knowledge.

Resources

Area Agencies on Aging

www.namaging.state.nm.us/aaa.aspx

City of Albuquerque / Bernalillo County

http://www.cabq.gov/family/income-eligible-services/senior-services/senior-services

Non-Metro Area Agency on Aging

Indian Area Agency on Aging

http://www.nmaging.state.nm.us/

Navajo Area Agency on Aging

http://www.naaa.navajo-nsn.gov/

Aging and Long Term Services Department

http://www.nmaging.state.nm.us/

Aging Network in New Mexico

http://www.nmaging.state.nm.us/senior-services.aspx

New Mexico State Plan for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias

http://www.nmaging.state.nm.us/uploads/FileLinks/93d89f60b10b4732be44e6c31f403060/Alz_State_Plan.pdf

New Mexico State Plan for Family Caregivers

Older Americans Act

https://acl.gov/about-acl/authorizing-statutes/older-americans-act

References

Bandeen-Roche, K., et al. 2015. “Frailty in Older Adults: A Nationally Representative Profile in the United States.” Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 70 (11): 1427–34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv133.

Block, E., and W. McGrath. 2019. Infected Kin: Orphan Care and AIDS in Lesotho. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Buch, E. D. 2018. Inequalities of Aging: Paradoxes of Independence in American Home Care. New York: New York University Press.

Dossa, P., and C. Coe, eds. 2017. Transnational Aging and Reconfiguration of Kin Work. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Geertz, C. 1983. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

Heinemann, L. L. 2016. Transplanting Care: Shifting Commitments in Health and Care in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Kittay, E. F. 1999. Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality, and Dependency. New York: Routledge.

Lehning, A. J., Smith, R. J., & Dunkle, R. E. 2015. Do age-friendly characteristics influence the expectation to age in place? A comparison of low-income and higher income Detroit elders. Journal of Applied Gerontology 34(2): 158–180.

Leibing, A., N. Guberman, and J. Wiles. 2015. “Liminal Homes: Older People, Loss of Capacities, and the Present Future of Living Spaces.” Journal of Aging Studies 37 (1): 10–19.

McLean, A. H. 2006. “Coherence without Facticity in Dementia: The Case of Mrs. Fine.” In Thinking with Dementia: Culture, Loss, and the Anthropology of Senility, edited by A. Leibing and L. Cohen, 157–79. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Mol, A. 2002. The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Richards, F. N. 2018. “Mothering Again: Kinship Matters among African American Grandmothers Caring for Grandchildren in Detroit, MI.” PhD diss., Michigan State University, East Lansing.

Robbins, J. 2013. “Shifting Moral Ideals of Aging: Suffering, Self-Actualization, and the Nation.” In Transitions and Transformations: Cultural Perspectives on Aging and the Life Course, edited by C. Lynch and J. Danely, 79–91. New York: Berghahn Books.

Sharkey, P. 2013. Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Thompson, C. 2005. Making Parents: The Ontological Choreography of Reproductive Technologies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-structure. Chicago: Aldine.

Van Gennep, Arnold. 2004 [1960]. The Rites of Passage. London: Routledge.

Wiles J. L., A. Leibing, N. Guberman, J. Reeve, and R. E. Allen. 2012. “The Meaning of ‘Aging in Place’ to Older People.” Gerontologist 52 (3): 357–66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr098.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2015. World Report on Ageing and Health. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf;jsessionid=9E7EA86ACAE21F99B46435A1C65C25C7?sequence=1, 2015.

Yarris, K. E. 2017. Caring across Generations: Solidarity and Sacrifice in Transnational Families. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

The Aging in Place: Challenges and Prospects summer salon was part of SAR’s 2019 Creative Thought Forum programs. Learn more about the Creative Thought Forum.

Salons are traditionally open to current SAR members. Learn more about our membership program and all of the benefits of becoming part of the SAR community.