From the desk of Kat Bernhardt, SAR’s Advancement Associate…

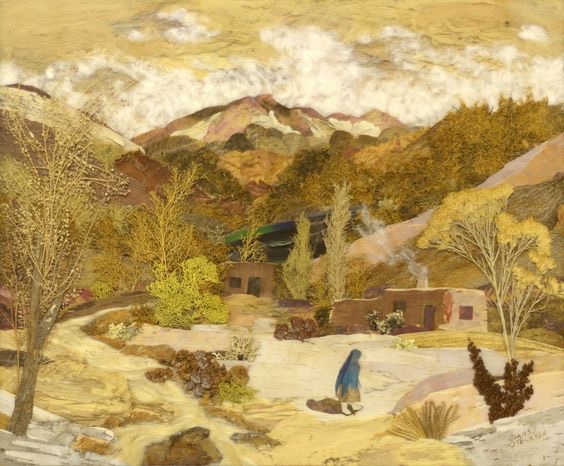

Growing up in the middle of Alaska, there was a window to another world on the wall of my living room. It was like no place I’d ever seen. There was a church that seemed to be made of clay pinched together by someone’s fingers. And there was a woman with a flared skirt, shawl, and scarf over her head. No one dressed like that in Alaska. I enjoyed stepping back to where it appeared to be a photograph or passage to another land and then move slowly forward to find just that point when the optical illusion fell away and I could see the leaves, the moss, the bark.

Before I knew it, I was listening to online lectures and creative thought forums. “Senses of Place” was the series I first attended. I took so many notes. What gives places their meanings? Are places living organisms? Do they gather meaning from those who pass through? Or is it the other way around?

It seems Santa Fe is a place that either repels or embraces. Santa Fe embraced my great grandmother, and it embraced Amelia Elizabeth White who lived for so many decades where the School for Advanced Research (SAR) is today, bequeathing the land to SAR at the time of her death in 1972.

I’ve always felt like a rootless nomad. No place belongs to me, although I carry with me the many waypoints all over the world that are part of who I am. Everywhere I’ve ever been has taught me something. It’s never seemed possible that anyone can really own a place no matter the amount of fences built, surveys mapped, and currency exchanged.

Margaret Atwood, who will be in Santa Fe for the Santa Fe Literary Festival this month, has a beautiful poem about the idea of owning a place. It’s called “The Moment” and includes these words:

“You own nothing.

You were a visitor, time after time

climbing the hill, planting the flag, proclaiming.

We never belonged to you.

You never found us.

It was always the other way around.”

As I joined the staff of the School for Advanced Research, getting to step behind those gates and walls and glimpse the strata of its history and mission, I wondered what the place would come to mean to me and how it would shape my identity.

Although they died the same year, Amelia Elizabeth White was from a different generation and social class than my great grandmother. She was one of the vanguard of women who came out west to forge new identities in the 1920s.

Just a few months ago, Nancy Owen Lewis and I sat across a lunch table wondering if they were friends or acquaintances. We agreed that while Amelia Elizabeth was old enough to be my great-grandmother’s mother, the main thing that divided them was social class. Amelia Elizabeth had money and status. Pansy did not.

It was the one time I met the beloved researcher and writer. I will carry with me the memory of this conversation and the way Nancy Owen Lewis’ eyes lit up at the suggestion of a chocolate dessert. I will also carry her admonition that stories don’t get told on their own; one must fight to tell them.

Pansy Stockton knew about fighting. She survived and ultimately became wealthy solely from the sale of her art. Sometimes I forget what an achievement that was for a woman living alone at that time.

While Pansy ended up coming to Colorado in a late model covered wagon thanks to her father’s determination to have the true Old Santa Fe Trail experience in spite of the advent of trains, Amelia Elizabeth and her sisters Martha and Abby began their lives in luxury on 51st Street between Park and Lexington, not far from Rockefeller Center. Their father, Horace White, owned two newspapers: the Chicago Tribune and the New York Evening Post. Horace instilled in his daughters a sense of social justice, so they went to Europe with the Red Cross during the first world war. And when they returned, they poured their time and money into causes that they believed were worth championing. They provided opportunities for Native Art to be valued as art rather than ethnography, bringing San Ildefonso artists Awa Tsireh and Oqwa Pi to New York City to show their work in 1931.

As I learn the history, I keep in mind these important words by L.P. Hartley at the beginning of his novel The Go-Between, “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.”

I enter the world of the past as I would a market in Marrakesh or a gamelan concert in Indonesia, expectations put aside, open to new ways to demonstrate grit and generosity of spirit.

It was when Amelia Elizabeth and her younger sister Martha drove from New York in a touring car to see the solar eclipse at Mount Palomar, California, that they stopped in Santa Fe, to get their hair done as the story goes, and decided it was an ideal place to realize their dream to raise wolfhounds. In 1923, they bought the old Benito Garcia house and an acre and a half of land.

They hired artist William Penhallow Henderson to create more adobe buildings as they expanded their residence. Together, they established a nationally respected wolfhound kennel named after an Irish castle: Rathmullan.

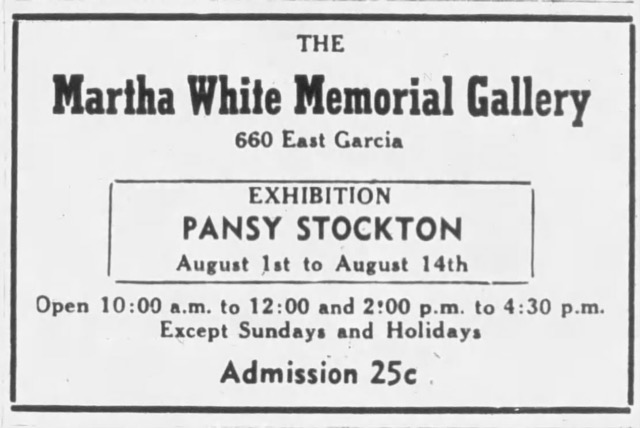

In 1937, after a trip to Ireland, Martha died of pneumonia according to the newspapers of the time. Amelia Elizabeth expressed her grief by asking John Gaw Meem to build a gazebo in her honor. She also opened the Martha White Memorial Gallery in December 1941 where SAR’s resident scholars live today.

John Sloan was first to show his work at the Martha White Memorial Gallery. Then followed 35 oil paintings by the man who built the three rooms they hung in: William Penhallow Henderson. Next came Gustave Baumann, Josef Bakos, the modern artist Raymond Jonson, and a posthumous exhibit of Gerald Cassidy’s work. Will Shuster stirred things up by making a series of life and death masks for his show. He made life masks of Pulitzer Prize winning writer Oliver La Farge and dancer Jacques Cartier, both Santa Fe residents, and a death mask of visual artist Howard Kretz Coluzzi. There’s a description of how he made the life masks; I don’t want to know how he was able to make the death mask.

Through the summer, Dorothy Stewart, Theodore Van Soelen, Alfred Morang, and Randall Davey held shows in the Martha White Memorial Gallery. Proceeds from the sales of the work went to fund the Santa Fe Animal Shelter founded by Amelia Elizabeth White in 1939.

In August 1942, my great grandmother Pansy Stockton showed her work in the Martha White Memorial Gallery. After years of going back and forth between Denver and Santa Fe, Pansy made the permanent move, building a kiva studio with her own hands and living alone there at Fremont Ellis’ San Sebastian Ranch ten miles south of Santa Fe.

Amelia Elizabeth White hosted a tea in Pansy’s honor attended by more than 50 guests, including Pansy’s good friends Fremont and Lencha Ellis, close friend Pop Chalee, John Sloan, Bee Binkley, Will Shuster, Josef and Teresa Bakos, Ina Sizer Cassidy, dancer Jacques Cartier and his partner Ray Baldwin, Taos reporter Regina Tatum Cooke, and, also from Taos, world opera singer Eduardo Rael.

According to an article in the Santa Fe New Mexican, the gallery gazers were so eager to view Pansy’s sun paintings that they deserted an enticing smorgasbord just as John Sloan arrived. As retold years later, “Quoth Sloan, upon the entrance and viewing the situation, ‘I believe that her bark is better than the bite.’” (Santa Fe New Mexican, July 17, 1949)

Sloan’s remark has an added layer of wit now that I know the gallery was on the site of a dog kennel.

Eighty years have passed from that moment in time. Now, I pass by that old gallery every day.

I invite you to do the same. It is my joy as a staff member to invite you to view the multi-layered historical strata of the School for Advanced Research (SAR).

—Kat Bernhardt, SAR Advancement Associate

If you enjoy sharing the rich history of Santa Fe, we are in the process of training docents to give tours of the SAR campus. If you are interested, please contact Kat Bernhardt at (505) 954-7230 or bernhardt@sarsf.org.