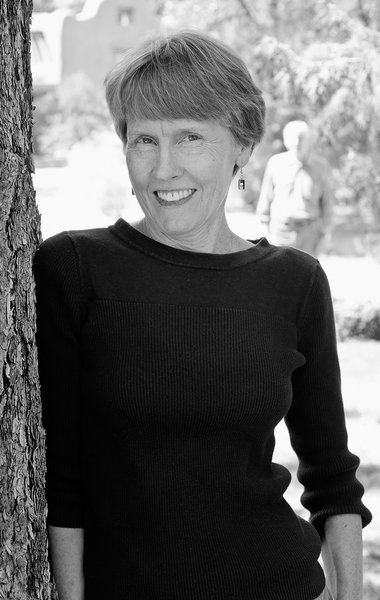

Catherine M. Cameron

2010-2011

Weatherhead Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Professor

Department of Anthropology

University of Colorado

Captives: Invisible Agents of Culture Change

Despite the fact that what Catherine Cameron calls “the long, sad tradition of captive-taking” has been practiced in societies of all social levels around the world throughout much of history and prehistory, few archaeological studies have explored the role of captives in culture change, especially in non-state societies. “Captives, who were mostly women and children, may have profoundly influenced developments in language, social organization, ideology, and technology,” said Cameron. Her book is the first to examine in detail the contributions of this surprisingly ubiquitous category of social person in the past. “Historians have not ignored these people, but generally archaeologists have not yet taken them into consideration as agents of change,” she said.

“As archaeologists, we ask ‘How do cultures change and interact? How did a pottery design get from here to there, for instance?’ There’s trade, the exchange of goods. Sometimes there’s intermarriage or migration. Some point to elite interaction. But non-state societies were battling constantly, dragging people back and forth. I suggest that these captives were bringing pottery designs, and so much more, to the societies they joined. I want to illuminate the remarkable changes captives wrought in the societies they entered. I argue that captives, who were frequently women, brought into the society of their captors novel technologies, ideologies, and social behavior, transforming that society in the process. If we look at captives as a source or method of culture change, it would really make a difference. That’s the perspective I’m developing.”

Utilizing worldwide ethnographic, ethnohistoric, and archaeological data, as well as captive narratives, Cameron’s book includes an overview of captive taking, its global scope and pervasiveness, and its selective focus on women and children. “The scale of captive taking is startling. Captives, especially captive women, were present in societies of almost every socio-political level from bands to states and in societies on every continent. Captives were typically obtained during raids or warfare, although some were traded, given as gifts, or taken for repayment of debt. They were also accrued as capital and otherwise treated as commodities. Captives were overwhelmingly women and children, and in some cases their acquisition was a primary goal of warfare.” Her book explores factors that affect the social person that captives become when they enter captor society, the effect of captives on social boundaries, how captives transmit practices from their natal culture into the culture of their captives, and how captives affect the creation of power by serving as followers and laborers for their captors.

Captives did every sort of work imaginable—from agriculture, carpentry, and masonry to craft production and household tasks, including childcare. “Archaeologists should be especially interested in the role of captives in the production of crafts that may be visible archaeologically.” Cameron’s research examines not only what captives brought to the societies they joined—such as new technologies, cuisines, and religious ideas—but also what allowed or prevented them from contributing to those societies. In some situations, captives might have assimilated as wives while in others they became slaves. “If you are a wonderful potter but now a slave in a Greek silver mine, you’re not going to be introducing any pottery designs because you’re not being given the opportunity to do that,” she said.

Cameron’s goal is to create models that can be applied to understand prehistoric cultures. “People aren’t just going to the market and exchanging pots. There are other ways in which they are interacting, and warfare is not just about taking territory or about imposing your selves on another group. Often, it’s about stealing people, and we can’t ignore that these people existed. As archaeologists, we need to start looking for the material evidence, and we need to use that in our models of intercultural interaction,” she said.

“I contend that unless we recognize the potential contributions of captives, our explanations of culture change are destined to be incomplete or even incorrect. This is a twist of the kaleidoscope that I hope will allow archaeologists to bring into focus people who, after suffering violent displacement, disappear into a foreign society. While culture change is frequently linked to trade or migration, uprooted young women may also have been a driving force behind the transmission of cultural practices.”