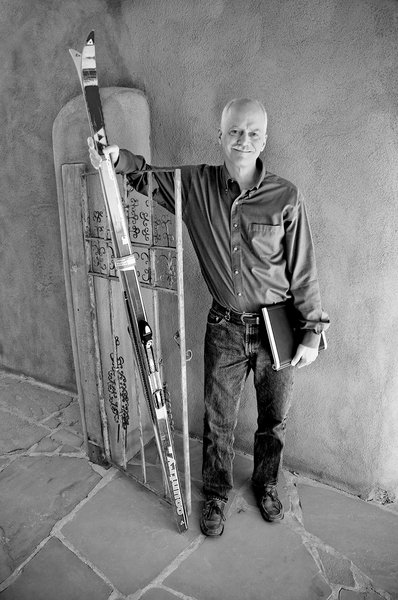

James A. Trostle

2009-2010

Weatherhead Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Professor and Chair

Department of Anthropology

Trinity College, Hartford

Illness on the Road: The Political Ecology of Remoteness in Esmeraldas, Ecuador

An indelible moment provides James Trostle with “an apt metaphor for life in the region where I have worked since 2003.” Late one night in Borbón, Ecuador, a teenage boy with a tattered T-shirt walked alone on a moving flatbed truck, under a streetlight. “The truck lumbered carefully down a dirt street…and the boy trudged slowly toward the back of the truck at the same speed, thus moving but not progressing,” writes Trostle. “Reaching the end of the truck, he turned and ran to the front, to play his game at the next streetlight. He combined action and stasis, playfulness and illusion, machine power and human muscle, public show and private satisfaction.”

The truck used a new paved road, completed in 2001, which links the northern Ecuadorian coast with the highland Sierra. “This is an ideal site in which to assess the health-related effects of rapid social change,” said Trostle, in this case the impact of this road on disease risk and transmission. With epidemiologist Joseph Eisenberg, Trostle designed and is conducting a long-term, multi-faceted, interdisciplinary research project with this goal, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. It began in 2003 and has been refunded through 2012.

“We randomly chose 24 of 120 villages in northern Esmeraldas province, some on the paved road, some already or soon to be reached by dirt logging roads, some still remote and accessible only by river,” said Trostle. “In this sense our design is a classic ‘natural experiment,’ in which we take advantage of existing local variation to access the impact of particular social changes on human health.” The interdisciplinary team has visited each village every six months, and full-time ethnographers circulate regularly. People in each village measure the changes in disease every three days. The study focuses specifically on the health of populations rather than on individuals. “It’s sometimes difficult to understand what actually determines the health of a group of people if you look only at what individuals are doing,” he said.

Playing with the idea that the road is an “unmoved mover,” Trostle admits that finding a narrative structure to tell this highly complex and nuanced story is a challenge. After the road is built, “in some ways it ‘disappears’ from consciousness, but all these things happen upon it and the road sets in motion all the people who move on top of it with products and messages and vehicles. This inanimate feature of the environment is continuing to facilitate all these processes that its original construction set into motion. How do we ‘see’ a road with ethnographic tools? How to move back and forth between the construction of a road, the movement of the people and products on that road, and the various pathogens transmitted across a transformed regional landscape?” To address this challenge, he plans to write about people and objects both at rest and in motion, including a chapter centering on the “ethnography of a bus,” and another (called “The road to hell is paved with good intentions”) examining the history of the many failed development projects in the region.

This unique research project employs the concepts and methods of “cultural epidemiology,” an approach Trostle presented in his 2005 book Epidemiology and Culture that links culture to human health at population scale. Moving beyond a standard “risk factor” analysis, Trostle and his team are drawing upon systems thinking and the social sciences in innovative ways. “We want to investigate the factors that increase the probability of transmission of diseases such as diarrhea across a landscape,” he said, “and we are including attention to culture and society as a force. It’s not just about what people eat and drink, it’s also about how they associate—what do they do together? These factors aren’t usually considered in studies of infectious disease transmission.”