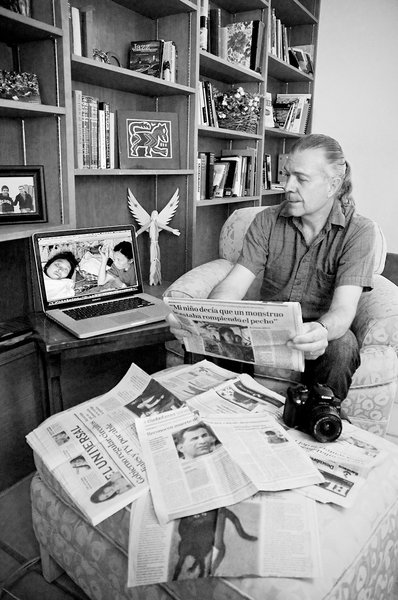

Charles L. Briggs

2009-2010

Weatherhead Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Alan Dundes Distinguished Professor of Folklore

Department of Anthropology

University of California, Berkeley

Bats, Rabies, Reporters, and the Wrath of the State: On the Limits of Anthropological Knowledge

In July 2008, anthropologist and Weatherhead Fellow Charles Briggs and public-health physician and SAR research associate Clara Mantini-Briggs, both in residence at SAR this year, returned to the Delta Amacuro in the Venezuelan rainforest to follow up on work they had done with the indigenous Warao group during the 1992–93 cholera outbreak. That research resulted in their 2007 J. I. Staley Prize-winning book Stories in the Time of Cholera: Racial Profiling during a Medical Nightmare. They returned to the Delta in 2008, using the cash award from the 2007 Staley to collaborate with local communities in developing innovative health policies and practices. “But a conversation with indigenous leaders Conrado and Enrique Moraleda changed everything,” said Briggs.

“They said, ‘We are in the midst of an epidemic of an unknown disease.’ It appeared the illness was 100 percent fatal. They asked—practically ordered—us to drop what we were doing and work with them to document the situation, diagnose the disease, and take our findings directly to the national capital in Caracas.” Together, Briggs and Mantini-Briggs worked with the Moraledas, an indigenous healer, a nurse, and the communities to document an outbreak of what appeared to be bat-borne rabies. Because of their previous work with the Venezuelan government on the cholera epidemic and their national study of the government’s very successful health initiative, Mission Barrio Adentro, Briggs and Mantini-Briggs were stunned by what happened when they arrived in Caracas.

“The health ministry officials refused to see us, attacked us publicly, discredited our findings, and launched a criminal investigation,” recalled Mantini-Briggs. “The horrific figure of the vampire bat and the government’s focus on suppressing the report created a media spectacle—some 30,000 media outlets worldwide carried the story. But a one-page statement on the health ministry’s website asserting that ‘there is no rabies in the delta’ ended the controversy. The state had reclaimed its monopoly over the production of knowledge about public health,” Briggs said. “Once reporters accepted that the state was the only legitimate producer of biomedical knowledge, statements by government authorities helped reinscribe the official story that had emerged from the 1992–93 cholera epidemic—that the Warao are poor, dirty, superstitious Indians who are incarcerated by their culture and incapable of even receiving biomedical knowledge.”

The fact that the Delta’s indigenous health leaders had now not only organized their own communities around a health emergency, but also recruited and directed an anthropologist and public health physician to help investigate the mysterious epidemic seemed beyond what the government health ministry could comprehend—or tolerate. The health of the poor has been a top priority of Venezuela’s national political agenda, Briggs pointed out, “but how has racialization impeded the transformation of biomedical concepts and practices in the Delta Amacuro, and how did it structure the government’s response to this recent report?”

“Charting encounters with a disease, racial inequality, journalists, and a pro-poor revolutionary state, our book will explore how far states will go in transforming assumptions about ‘the people’s’ role in producing biomedical knowledge. It examines to what extent new visions of global health and activist configurations of civil society can challenge assertions that national sovereignty and bio-security require tightly-regulated schemes of surveillance and regulation. In doing so, our book will chart the complexities of producing anthropological knowledge in a situation in which it could make a difference—and that sharply defined the limits of scholarship and activism,” explained Briggs.

From photographic and video documentation collected at the request of the indigenous health leaders, Briggs and Mantini-Briggs are also producing a film about this incident, directed by UNM Professor Miguel Gandert and with the participation of indigenous UC-Berkeley graduate student Kalim Smith. “We hope the film will help us reach beyond the anthropological community to a much larger audience,” said Mantini-Briggs. “There are messages here about human dignity and justice, and about the possibilities that people themselves can be engaged in understanding and producing valuable knowledge about the health problems in their own communities.”