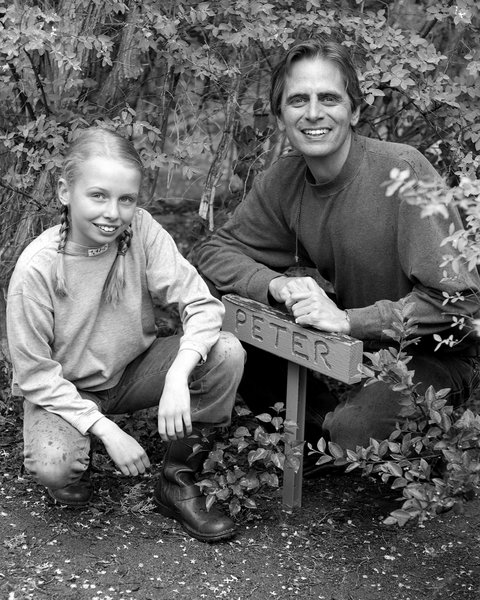

Peter Redfield

2007-2008

Weatherhead Resident Scholar

Affiliation at time of award:

Associate Professor

Department of Anthropology

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Life in Crisis: The Ethical Journey of Médecins Sans Frontières

Over three decades, the emergency relief organization Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontires (MSF) has provided exemplary medical services to crisis areas around the world. “We find out where conditions are the worst, the places where others are not going, and that’s where we want to be,” states a recent mailing. Roiling beneath MSF’s unparalleled technical proficiency, however, are ongoing philosophical dilemmas that strike at the heart of contemporary humanitarianism.

“MSF demonstrates an essential tension between ethics and action, protesting the very conditions in which it seeks to effectively intervene,” says Peter Redfield. His ethnographic and historical study of MSF traces the context of its emergence and continuing reformation as an organization constantly striving to remain experimental and uncomfortable with its mission. Established in 1971 by French physicians and journalists who sought to establish an independent voice to condemn human suffering, one that would not mute itself in the face of controversy, today MSF has projects in more than seventy countries, an annual budget of nearly half a billion dollars, and a Nobel Peace Prize awarded in 1999.

Redfield is particularly interested in the border of ethics and politics, and views MSF as an exemplar of the desire to uphold critical values, even as the organization has become a global institution. “Témoignage, or bearing witness in the face of neglect, violence, and inhumanity and advocating on behalf of the suffering, is one such core value, while the ethic of engaged refusal is another. For MSF, the act of responding to human suffering is essentially an embodied refusal to accept it. Paradoxically, the outrage is that you have to be acting at all,” Redfield says. MSF’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech stated that humanitarianism is not a tool to end war or to create peace. It is a citizen’s response to political failure. It is an immediate, short-term act that cannot erase the long-term necessity of political responsibility.

Redfield also investigates the impact of the shifting status of human life as both a moral good and a matter of political and ethical concern on contemporary humanitarianism. Dramatic changes in global conditions and expectations in a post-colonial world have strained the philosophical underpinnings of MSF and similar organizations. Cholera and malaria pose one set of problems for emergency relief interventions, HIV-AIDS and pharmaceutical supplies another, and genocidal violence still another. The tragedy in Rwanda, fraught with political complexity and unimaginable violence, provoked the French branch of MSF to declare in frustration: “You can’t cure genocide with doctors.” At the same time, the group struggles to limit its ever-expanding mission by stopping short of development work, and opposes trends to justify military actions on humanitarian grounds. Its emphasis on mobility often leaves local communities behind, even in longer-term sites like Uganda.

According to Redfield, “With its unrelenting commitment to responsiveness and reflexivity, MSF represents the growing edge of the human engagement with the significance of suffering and the value of life. There are few organizations that so neatly represent a moment in history.”