PIN,WEL,TAH MO,LO,MOH

THE UNPAINTED HISTORY OF PICURIS POTTERY

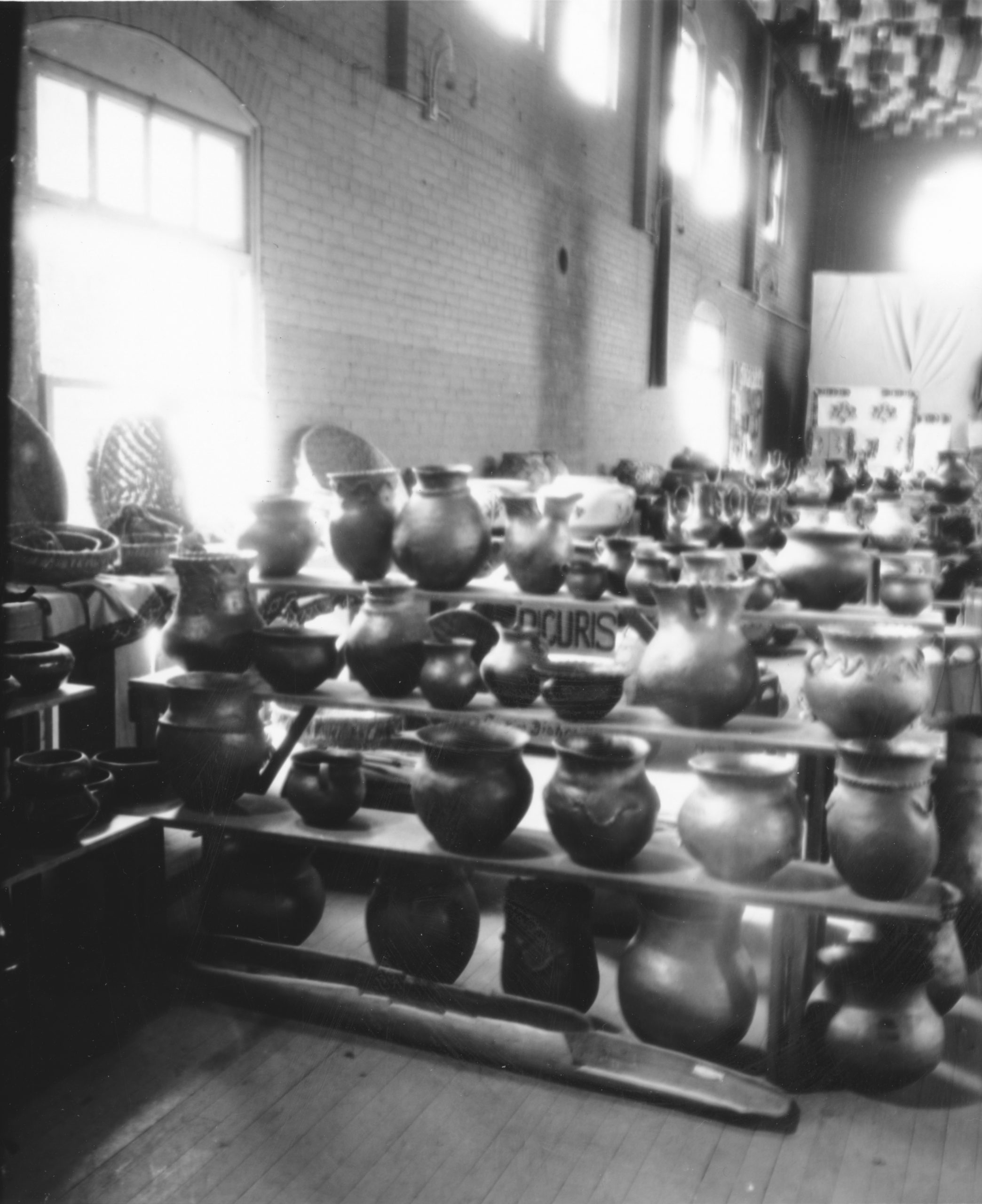

Early collectors of the 20th century were drawn to the painted pottery of the Southwest for their beautiful and unique designs incorporated with symbolism. The unpainted micaceous pottery from Picuris, however, was not collected or documented as much as pottery from other Pueblos. The reason for this is twofold: one, Picuris’ remote location made it difficult for collectors to access it, and two, pottery from Picuris was deemed utilitarian and did not seem as interesting to the Eurocentric eye at the time.

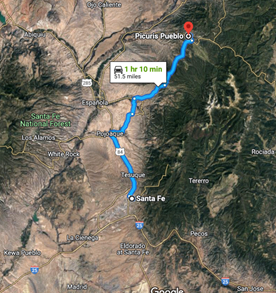

Picuris Pueblo, also known as Pin, Wel, Tah (mountain pass place), is a Tiwa speaking Indigenous nation located in the hard-to-reach Sangre de Cristo mountains of northern New Mexico. The Picuris pots chosen for this exhibition are from the collection at the Indian Arts Research Center (IARC) at the School for Advanced Research (SAR). Because these pots are unpainted, the artistry of these pieces relies on form and structure. Despite there being very little documentation about Picuris, and about these pots, they still tell a rich story of perseverance. To understand Picuris Pueblo pottery is to understand a bit of its history.

Curated by Wayne Nez Gaussoin, 2022-2023 Anne Ray Intern.

Modern route from Santa Fe to Picuris Pueblo[1]

TRADING WITHOUT BORDERS

Picuris Pueblo is one the oldest living inhabited pueblos of New Mexico. There is a long history of pottery in Picuris; archaeologists have found pottery sherds at the pueblo dating back to 900 A.D. Soil pigments registered some sherds as being from as far away as Chaco Canyon, Oklahoma, and Cuartelejo, Kansas. These findings suggest that there was an exuberant amount of trading going on throughout the Southwest and beyond. In fact, Picuris was known for its trading and living relationships with Taos Pueblo, the Jicarilla Apache, the Kiowa, and their southern Tewa speaking neighbors.[2] Little is known about the gap in time between this older pottery and the micaceous styles Picuris is known for today.

SPAIN INTO MEXICO

Over the course of the Spanish invasion in the 1600s, Spanish conquistadors had little contact with Picuris, labeling them as “…the most indomitable and treacherous people in the whole kingdom.”[3] Despite this limited contact, Picuris, like many other tribes, suffered greatly from cultural persecution and mass genocide due to new diseases. From the 1600s until about the mid-1700s, Picuris people continued to create micaceous pottery. According to Duane Anderson, author of All That Glitters, the earliest evidence of micaceous pottery at Picuris can be traced to the early 1600s.[4]

Picuris Pueblo persevered through the Spanish invasion and into Mexican authority. During this period, relationship dynamics between the Spanish and Picuris shifted. The Spanish started to settle near communities to help protect the dwindling population of Picuris, caused by the turmoil that they had wrought, and to convert them to Catholicism. These new dynamics resulted in Puebloans and Spanish integrating even further into each other’s lives, communities, and practices.[5] The Spanish began creating micaceous pottery alongside Pueblo makers and servants. It is hard for archeologists to document exactly who made what, as most pottery was not signed.

AMERICAN CONSUMERISM

At the dawn of the 20th century, the west was a new frontier that was mostly untouched by Americans. Tourists from out east started coming in swaths to the Southwest on the newly built railroad to explore the wild west. This tourism boom had a huge impact on the creation of pueblo pottery as well as on the intentions of potters. Many Pueblo potters began to experiment with their work to meet the demands of the tourist market, moving away from utilitarian styles.[6] Because Picuris is in a remote location and was bypassed by the railroad and the majority of tourists, it was easy to overlook. Micaceous wares from Picuris were not considered in the same class as other pottery artware.

PAVED ROADS TO GLITTERY CLAY

“Juan Jose Martinez is indicative of the kind of experimentation that was taking place [at Picuris] …[his] toolkit indicated that he was using a beer can opener and broken files along with an assortment of bolts, nails and screws to produce tool impressed designs on his wife’s pottery.”[8]

PRACTICALITY AS ART

There have been many changes throughout the twenty-first century that influenced how micaceous pots are used and viewed. Metal pots became more widely used for cooking and micaceous pots were being used less for utilitarian purposes. In the 1950s, forced assimilation and integration of Pueblo people into American culture by resulted in a renewed interest in Pueblo pottery. Non-Indigenous artists began making and selling micaceous pottery which affected the sales and perception of Indigenous potters.[9] Newly established gallery owners, like the traders who came before them, took control of the Native art market dictating who and what received critical attention. Also, organizations like the influential Southwestern Association of Indian Arts (SWAIA) created guidelines to determine what is and is not considered Native American art. These guidelines are both helpful and questionable to collectors and Native artists alike.

TRADITIONS CARRIED FORWARD

Picuris Pueblo tortilla plate. 1890-1900. Micaceous clay. 1 x 13in (2.5 x 33cm). IAF.1927. Photograph by Addison Doty. Copyright 2022 School for Advanced Research.

Excerpt from 2021 Rollin and Mary Ella King Artist Fellow Brandon Adriano Ortiz-Concha’s Artist’s Talk. View full video here.

Anthony Durand was a master potter from Picuris who learned from his grandmother, Cora Durand. Both were instrumental in preserving and reviving the Picuris style. Cora Durand represented Picuris Pueblo in a 1974 Smithsonian Institution exhibition and Anthony Durand sold his work professionally to the Millicent Rogers Museum shop in Taos and at the Santa Fe Indian Market (SWAIA). Anthony began to experiment by studying older style pots that were unsigned. His work is in various private collections and museums throughout the U.S.[10]

Anthony Durand Picuris Pueblo, jar. 1994. 9 ¾ x 12 1/2in (24.8 x 31.8cm). SAR.1994-7-3. Photograph by Peter Gabriel Studio. Copyright 2020-2021 Peter Gabriel Studio.

REFERENCES

[2] Adler, Michael A., and Herbert W. Dick, Picuris Pueblo through Time: Eight Centuries of Change in a Northern Rio Grande Pueblo, (William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies, Southern Methodist University, 1999).

[3] Hodge, Frederick Webb, “Hawikuh Bonework,” Indian Notes and Monographs 3, no. 3, (Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, 1920) quoted in Adler, Michael A., and Herbert W. Dick, Picuris Pueblo through Time: Eight Centuries of Change in a Northern Rio Grande Pueblo, (William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies, Southern Methodist University, 1999).

[4] Anderson, Duane, All That Glitters: The Emergence of Native American Micaceous Art Pottery in Northern New Mexico. 1st ed (School of American Research Press, 1999), 35.

[5] Ibid., 41-44.

[6] Ibid., 45.

[7] Ibid., 41.

[8] Ibid., 51.

[9] Ibid., 9-13. Some argue that micaceous pottery made by non-Indigenous artists lowers the market value of Indigenous made wares, while others argue that sharing a traditional artform educates non-Indigenous peoples to respect the clay and appreciate the craftsmanship that goes into making micaceous pottery.

[10] Ibid., 66.