Guest post by Emily Santhanam, 2020-2021 Anne Ray Intern

I arrived mid-morning at the Reception Center, the summer sun already high and bright. It had been a few months since I’d last visited campus, and over a year since I’d lived there as an Anne Ray intern. Returning now, I was reminded just how special Saturday mornings are at the School for Advanced Research (SAR): the birds chirping, leaves fluttering, breeze carrying on the wind like a spell.

Lucky for me, I’d spend the next hour in this place of beauty to experience the current version of the SAR Campus Tour led by Kat Bernhardt, Advancement Associate. “I like to think of the land, buildings, and stories of SAR like strata,” Kat said, “the layers of history that you view all at once. When you look at a rock formation, you often see many different layers of time that come together into something quite beautiful.”

Since 1907, the layers of SAR have been stacking, accumulating, and overlapping. As such, the tour would oscillate between past and present, individual and institution, archaeologist, artist, Afghan Hound—but I’m getting ahead of myself. To begin, we started, rightfully, in the present.

Kat set the scene of SAR’s mission through video format. First, a dive into the institution with Who We Are as narrated by President Michael F. Brown, and second, a feature on Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery. To have the Grounded in Clay exhibition so prominent in the tour introduction felt like an important decision; and inclusions like these, peppered between institutional histories and founder narratives, continued throughout the day.

Kat then launched into the origins of SAR, telling the stories of Alice Cunningham Fletcher, an anthropologist who wrote the proposal for the School of American Archaeology in 1906, and Edgar Lee Hewitt, the school’s first director. The institution, seeking to broaden its scope in 1917, changed its name to the School of American Research, and through the years, SAR shifted locations from the Palace of the Governors to the sprawling El Delirio home of Amelia Elizabeth White when she died in 1972, leaving her property to SAR.

In 2007, the institution adopted its most recent name of School for Advanced Research and reoriented itself as a nexus of artists and scholars. Each year, six or so Scholar Fellows, some with PhDs in hand and others in the dissertation process, spend nine months living on the campus, writing, researching (with help from interlibrary loans through the SAR Library), and providing peer review to one another. While there is scholar research relating to the Southwest, other projects are far more global, tackling subjects like politics and family in Brazil, race-making in Albania, and collaboration with the Maya Ixil Ancestral Authorities in Guatemala—a particularly impactful piece, given SAR’s Guidelines for Collaboration that seek to promote equity between museum collections and Indigenous communities.

Advanced Seminars, hosted in the 1920s-era Douglas W. Schwartz Seminar House, are another avenue through which scholars can gather, share research, and begin book conversations that sometimes lead to an SAR Press publication. With over 300 titles, the Press operates out of what once was the dog kennel (and later an archaeology lab expanded by John Gaw Meem in 1962). To better divide the archaeology staff and building from the White residence, a separate gate and entrance was built at that time—explaining why two entry/exit points can be accessed today.

With the context for the organization in place, Kat and I walked outside to better visualize what the property might have looked like fifty, one hundred, and even one thousand years ago. Facing the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, Kat said they remind her of “this place that has, for thousands of years, had many different people passing through it.” Ancestral Puebloans, Tewa, Southern Tano, Keres, Apache, Navajo, and others all at various points in time navigated the lands now known as Santa Fe. To emphasize the continued importance of place for those who live, create, and celebrate in the Pueblos nearby, Kat referenced the words of two former SAR scholars: Tito Naranjo (Santa Clara Pueblo), who wrote about Pueblo reverence for the land as a gift to be honored, and Rina Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo), who discussed the need to recognize the creative force and sacredness in all life.

The arrival of the Spanish set into motion complex and intwined cultural relationships that continue to this day. Kat showed me the first known structure on campus: the Benito Garcia House. Hotel cook Benito, his wife Julianita, and their six children lived in what is now the Bandelier scholar residence along Los Garcias Road, or the road of the Garcia family. Garcias lived all along the road in the early 1900s. When Julianita died, Benito and his children moved elsewhere, putting the house and land up for sale.

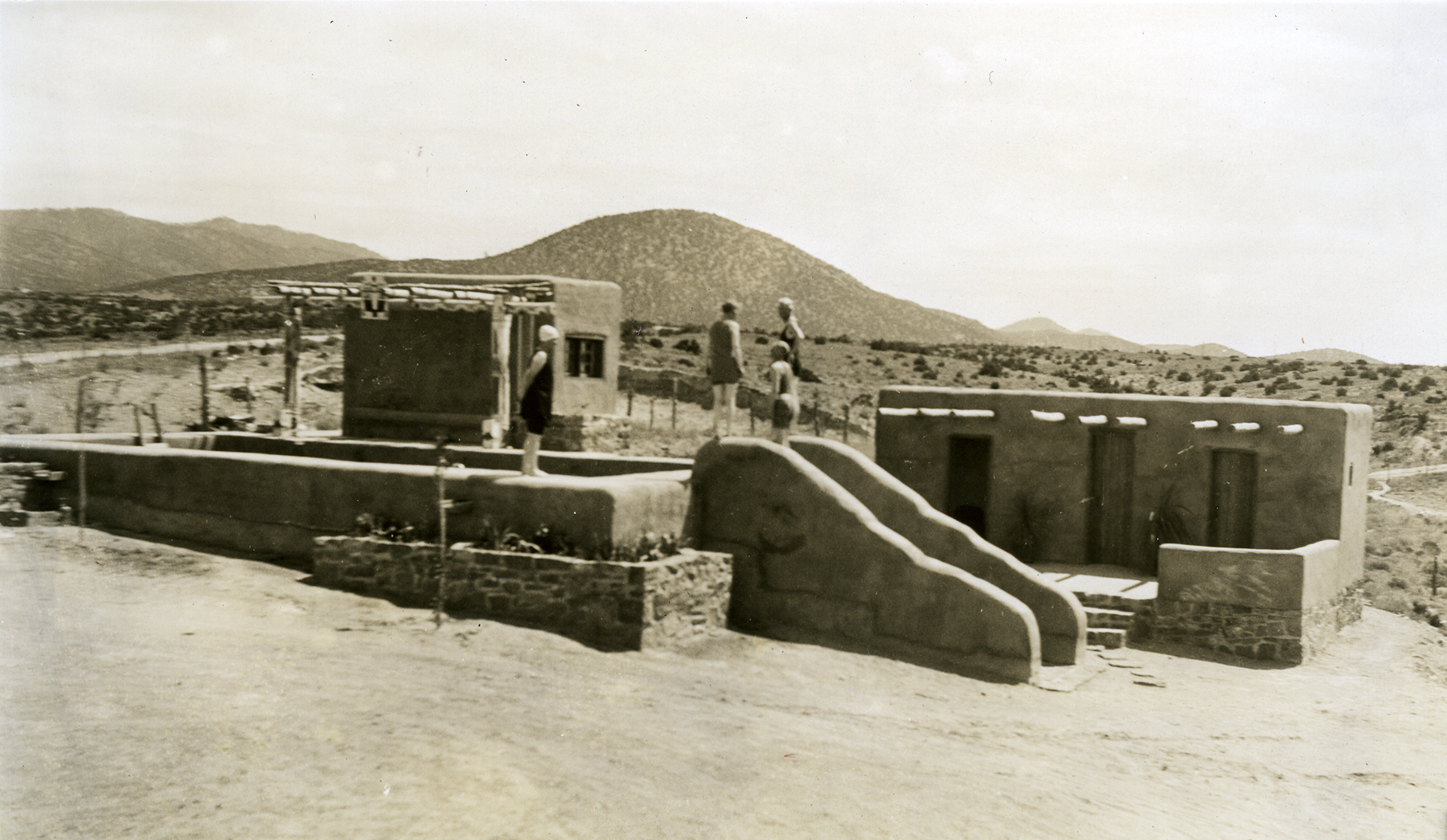

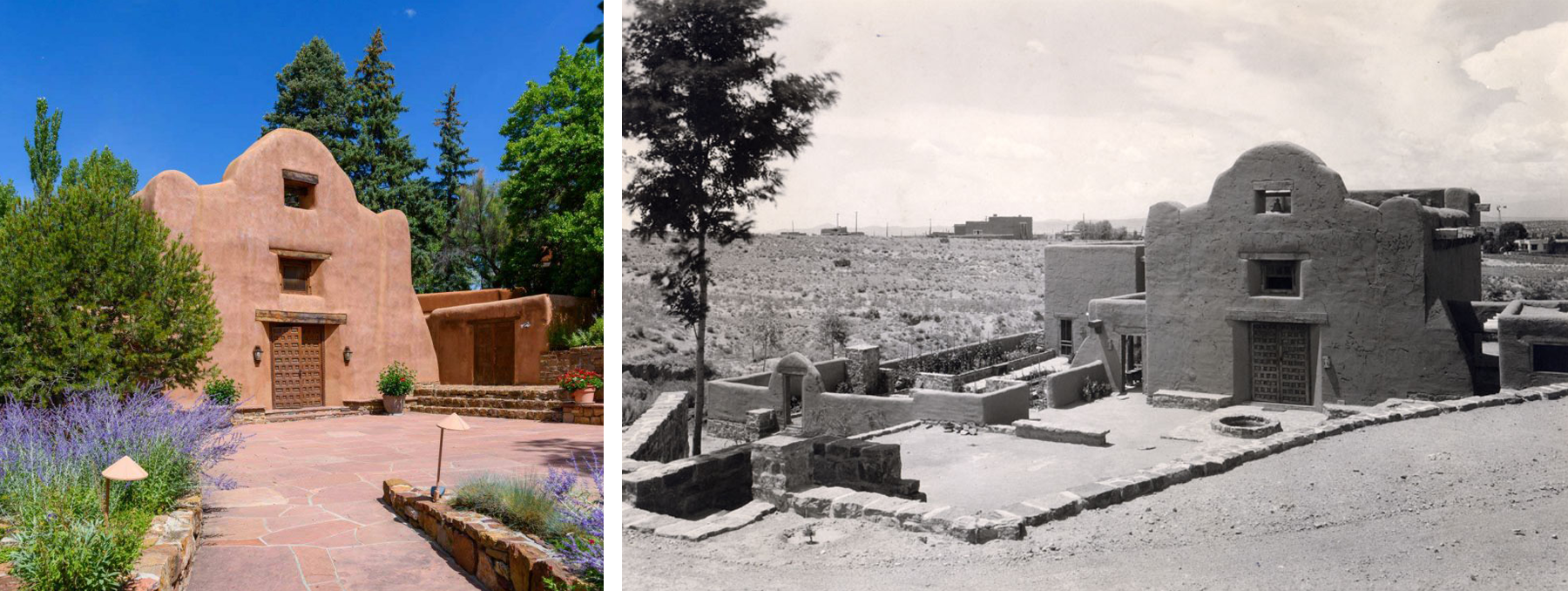

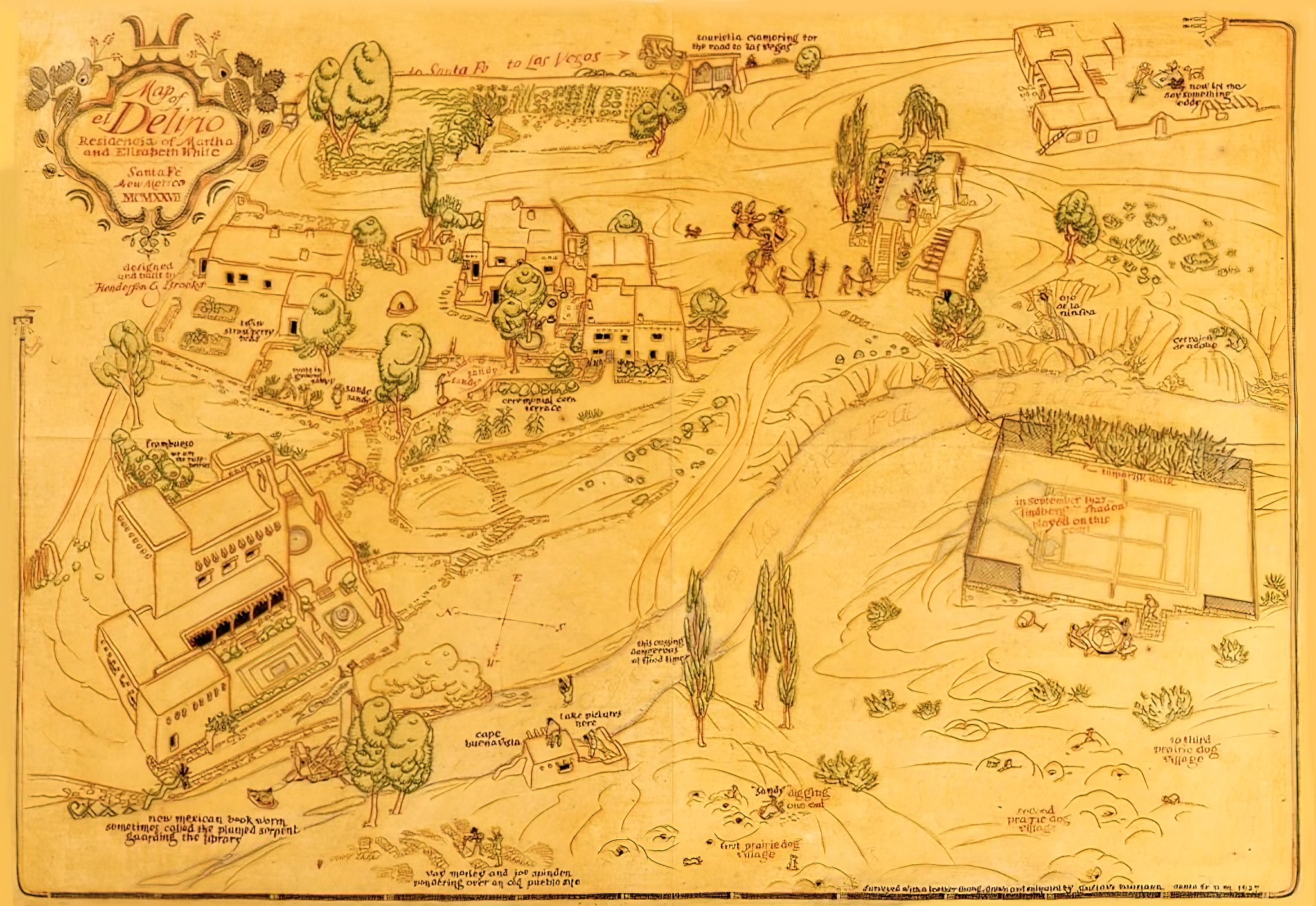

In 1923, a pair of wealthy New York sisters, Amelia Elizabeth and Martha White, purchased the Benito Garcia House and an acre and a half of land. Kat, printed photos in hand, showed me just how grand their plans were. By hiring artist (not architect) William Penhallow Henderson to design their expanded residence, the White sisters developed a whimsical and fanciful set of structures through the years, including Santa Fe’s very first swimming pool and a house to mimic Laguna Pueblo Mission (now the Administration Building).

We entered the El Delirio house where I was greeted by a new exhibition of works by bird painter Henate of Zia Pueblo (Spanish name Andres Galvan). Henate’s grandson, Zia potter Ulysses Reid, studied the work of his grandfather while he was a 2009 Native Artist Fellow, demonstrating layers within a family of artists at SAR. The exhibition, curated by SAR’s most recent Anne Ray interns, pleasantly reminded me of the collection I hung with fellow intern Sháńdíín Brown just a couple years back. Change is a beautiful, curious thing.

Next, we visited the former living room, now Dobkin Board Room where people gather for Native Artist Talks, Scholar Colloquia, or Creative Thought Forums. With its congregational size and upper balcony frequented by musicians playing for elaborate costume parties, it’s unsurprising that Amelia Elizabeth called it “the Chapel.” A tin chandelier from Mexico and an elk hide painting depicting a buffalo hunt by Shoshone artist Cotsiogo were among the artworks that graced the walls nearly a century ago and still do today. When tent canvas paintings by Oqwa Pi and Awa Tsireh were found rolled up in an adobe workshop years ago, they were restored, rehung, and the descendants of both San Ildefonso artists were invited to view the work.

Flipping on a spotlight to showcase a more recent piece by 2002 Native Artist Fellow Mateo Romero (Cochiti Pueblo), Kat read the artist’s words about the painting from his book, Painting the Underworld Sky:

The central figures are my brother, Diego Romero, and me dressed as faux turn of the twentieth-century archaeologists. Surrounding us is a series of Mexican pots painted as faux Ancestral Pueblo historic pottery. In the background, Roxanne Swentzell’s horse Toucha poses as a pack animal. The pothunters feverishly discuss the latest priceless artifacts they have recently pillaged from the earth…This is part of the conundrum of my time, the rapacity of the consumption, the speed at which we destroy the past to make a lackluster, frame-housed, linoleum-tiled future.

Stepping deeper into the building, I was amazed by just how many surprises there were along the way: enter the bathroom, and there’s Mayan-inspired tiling; turn the corner, and there’s a Gustave Baumann map; peer into the President’s office, and there’s a wall-sized altar screen brought back from Guatemala by SAR’s second president, archaeologist Sylvanus Morley. I lived on campus for nine months total, yet somehow missed these design delights. With every nook and cranny home to something special, I had to ask Kat: don’t you discover something new each time you lead a tour? She nodded and assured me,

We are constantly uncovering new information. Did you know there was a Poetry Festival right here on this campus in 1939? And in newspaper archives, we found San Ildefonso Pueblo artist Oqwa Pi’s own words when he first visited New York City to show his work in a gallery in 1931. The docents and I are constantly sharing and modifying based on the new things we learn. The tour will always be a living document subject to change.

Having spent nearly an hour with Kat at this point, I was far from shocked. The depth and detail of her knowledge, not to mention the infectious enthusiasm she shared along the way, made it clear she was a passionate learner. To add to, adjust, and alter the script as needed would only come naturally.

When we left the building, strolling past the Mirador (lookout), Billiard House, and tennis courts, we stumbled upon one member of a family of deer that call SAR home—a true testament to the serenity of the campus. And rightfully so, since just a few paces away was the dog cemetery, a resting place for the Irish Wolfhounds and Afghan Hounds the sisters cared for, as well as gravestones where Amelia Elizabeth and Martha White themselves were interred. Rather than feeling solemn or inaccessible, this light-dappled, leaf-thick section of campus had a calm and contemplative air. Kat opened up the silence, saying,

Amelia Elizabeth and Martha White were among the intrepid, tough-as-nails, independent-minded women who came to Santa Fe to realize their full identity in a place where women were not expected to be a certain way and could stand on equal footing with men. They redefined what it means to be a woman.

And still, the strata continued to build. From the Dubin Studio (currently supporting Native Artist Fellow Hollis Chitto, of Mississippi Choctaw/Laguna Pueblo/Isleta Pueblo descent) to the Indian Arts Research Center (my old stomping grounds that house over 12,000 items in its collection), to the old dog kennel (now SAR Press Building), to the former adobe workshop (now Library), the living histories kept unfolding. Did you know 2022 Native Artist Fellow Juanita Growing Thunder Fogarty (Assiniboine Sioux) sewed Ukrainian ribbon into one of her pieces as a demonstration of solidarity with the war-torn country? Or that Agatha Christie stayed in the Douglas W. Schwartz Seminar House? That dog scratches still grace the Press walls?

As we spiraled back to where we began, Kat reminded me that this was just one version of a program that’s ever-changing. “We’re very flexible about the tours,” Kat said. “We make alterations to how we do the tour based on who’s coming, their interest, and their time. It’s continually new.” Anyone—from architect to dendrologist—can walk SAR’s evolving campus tour in search of shade, story, and strata.