Reinventing the West: Southwestern Landscape from an Indigenous Perspective

At the turn of the twentieth century, the joint success of the railroads and tourist marketing efforts transformed the American Southwest into an “exotic destination.”[1] During the 1920s, white settlers from the east rode across the country on the Santa Fe Railroad following the demand to “Go west!”[2] This propaganda attracted entrepreneurs, tourists, and artists, all of whom played a role in crafting a romanticized vision of “the West.

This image continues today. When people envision “the West” they see a landscape characterized by a harsh, but beautiful, desert climate. The stereotypical view of the American West as a frontier, a “meeting point between civilization and savagery,”[3] was perpetuated by people such as Fred Harvey and the members of the Taos Society. Views like this exploited Indigenous peoples’ cultures and likenesses for profit and promoted a romanticized colonial ideal. White tourists embraced this vision of the West, and its’ Indigenous bodies, to take part in an imagined lifestyle that they felt entitled to. This idea can broadly be described as the White Imagination.[4] In reality, visitors’ understandings were superficial and disconnected from Indigenous ways of knowing about the land and their cultures. This exhibition deconstructs the White Imagination by prioritizing Indigenous knowledge of landscapes through their interpretations of their land.

Curated by Rachel Geiogamah (Kiowa), 2021–2022 Anne Ray intern.

THE WHITE IMAGINATION

Some well-known artists that fell in love with “the Land of Enchantment” (New Mexico), were the members of the Taos Society of Artists. The organization was founded in 1915 to promote artwork by the founding artists in addition to regional arts and culture of the American Southwest until they disbanded in 1927.[5] Although their works broadly depicted scenes of the Southwest, many of their artists were known for their portraits of Indigenous peoples, a practice that reinforced misrepresentation of the Indigenous Southwest.

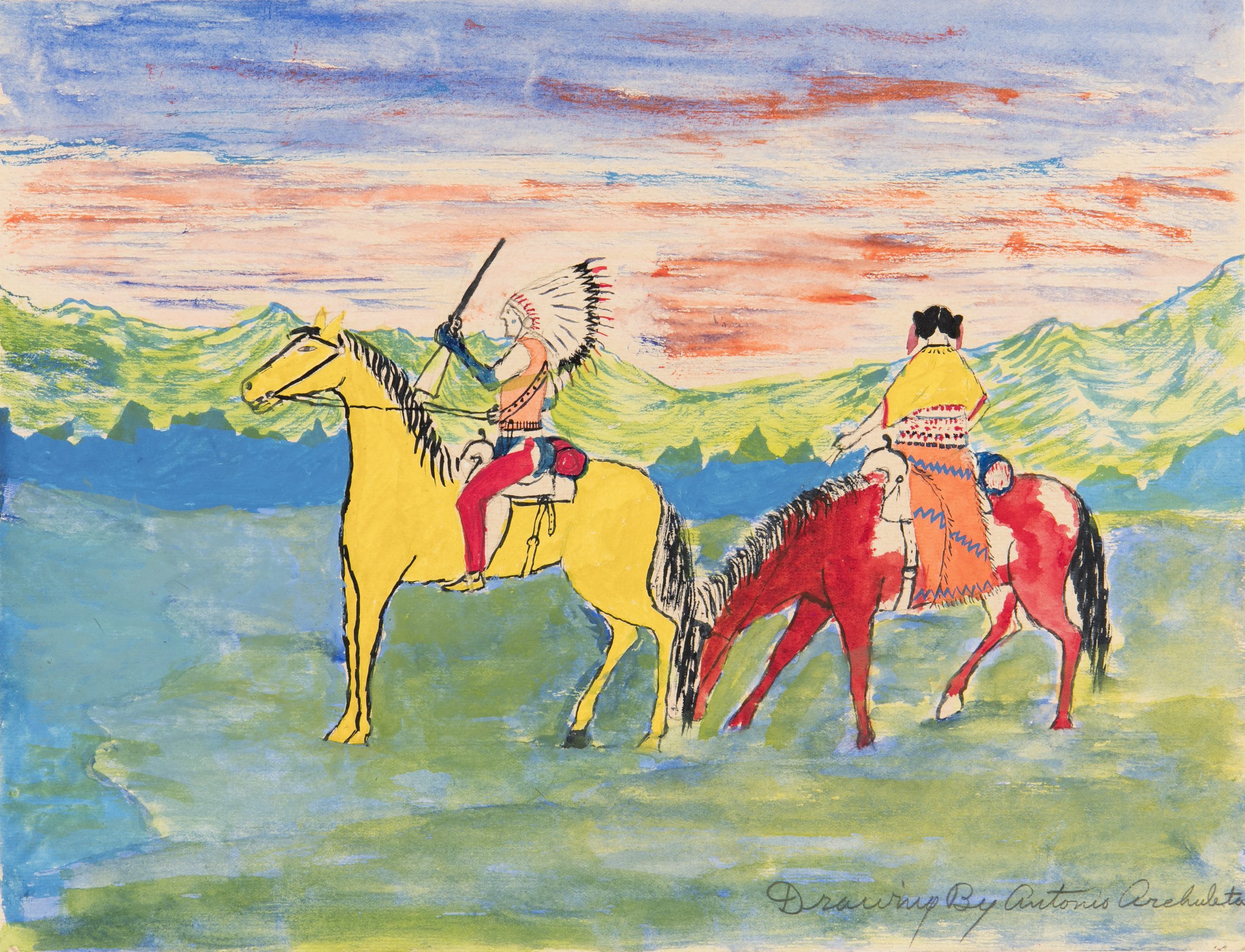

An example of one of these portraits is Eanger Irving Couse’s Tom-tom Player – Firelight. In this painting, you can see an Indigenous man stoically sitting by a fire in a featureless cave-like room with two pieces of pottery. Couse, like many artists, romanticized Indigenous lifestyles. In contrast, works by Antonio Archuleta and Beatien Yazz also depict Indigenous men, but with a very different artistic approach. Archuleta used vibrant colors and placed his figures in an outdoor scene instead of sequestering them to a void-like background. Similarly, while both Couse and Yazz illustrate a man by fire, Yazz’s depiction dresses the figure in clothing appropriate to the era. Both Archuleta and Yazz’s works contain similarities to the Couse piece, but more importantly, their works portray Indigenous life outside the realm of presumed mysticism. Outside of the studio, another way the Taos Society of Artists reinforced the White Imagination was by dressing up as Indigenous peoples.[6] The Taos Society of Artists were known within other art communities for their respect and well-intentioned attitudes towards Indigenous people, which falsely translated to them thinking they understood and captured the “spirit” of the people better in their works. The contrast of them “playing Indian” with them thinking they were being respectful shows the idea of the White Imagination at play.

SANTA FE STUDIO STYLE PAINTING

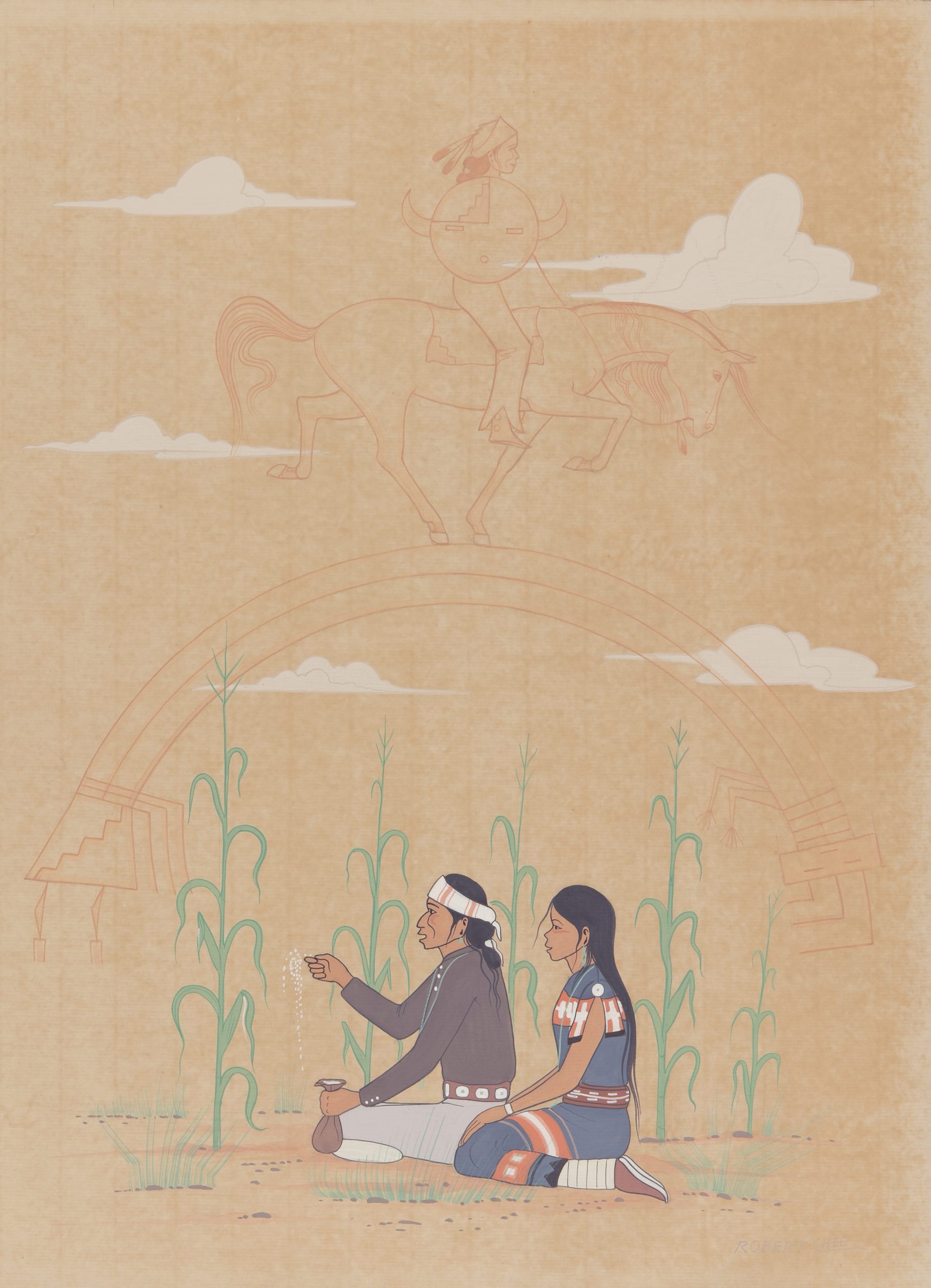

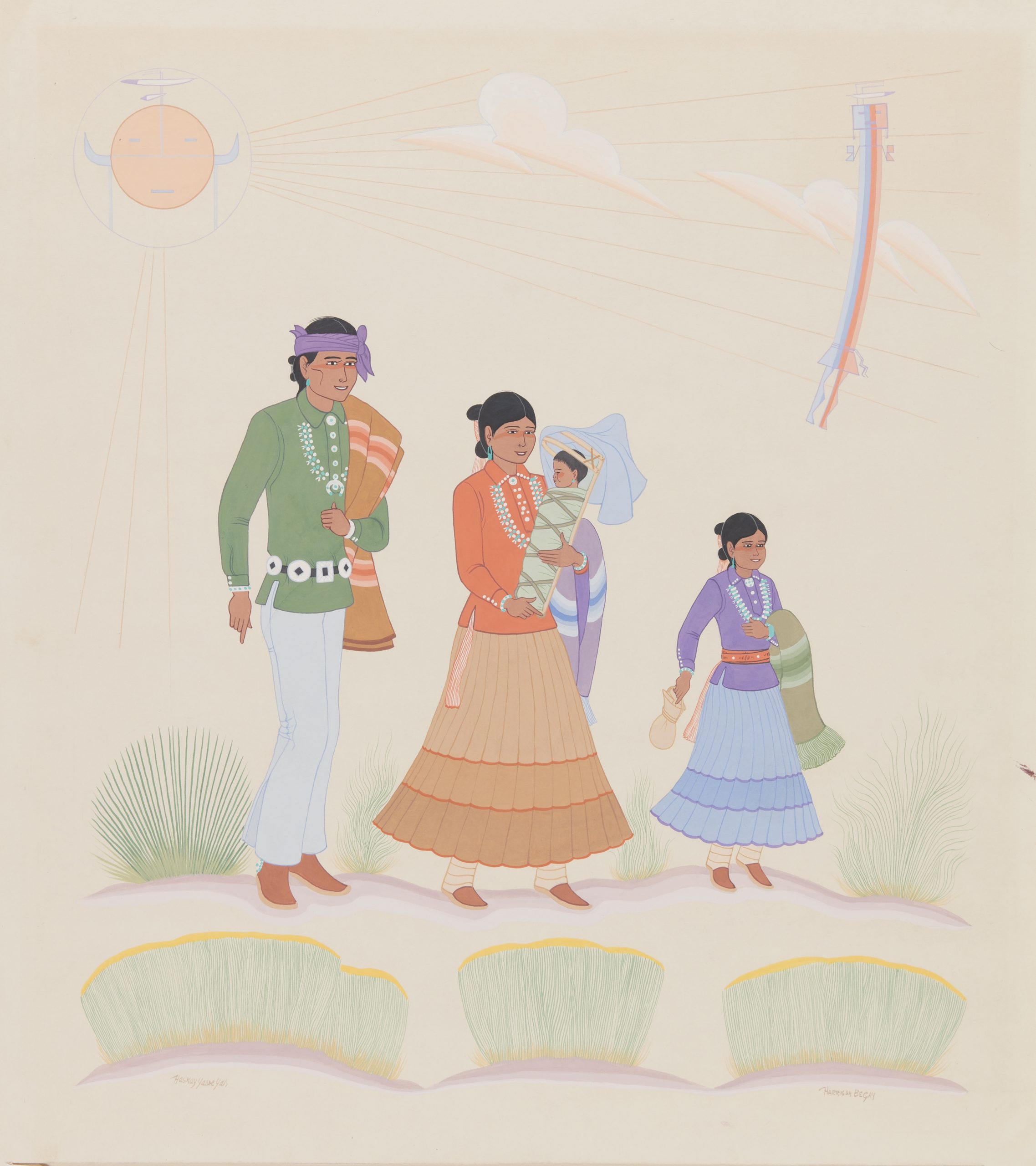

In 1932, Dorothy Dunn founded the first painting program at the Santa Fe Indian School in Santa Fe, New Mexico. This program, which became known as the Studio, launched the careers of several Indigenous artists and brought recognition to a specific style of painting: Santa Fe Studio Style painting.[7] Studio Style can broadly be recognized by its flat appearance and subdued earth-tones that depict traditional scenes of Indigenous life and culture. Although Dunn is often credited with creating this style, many artists in San Ildefonso and Hopi, including Fred Kabotie, were painting in this style years before Dunn came to teach in Santa Fe.[8] Additionally, teachers like Dunn severely limited what was considered Indigenous art and how their students were allowed to create. Dunn instructed students to paint in only the flat-style with no deviation so that the painting would be more “authentic”, and oftentimes against the wishes and artistic interests of the students.[9] Despite the limitations, these works are still an important part of Indigenous art history and for some artists, even provided a respite from homesickness. Kabotie recounts that when he first started painting: “Mrs. De Huff got me some drawing paper and water colors and I started painting things I remembered from home, mostly kachinas. When you’re so remote from your own people you get lonesome. You don’t paint what’s around you, you paint what you have in mind.”[10]

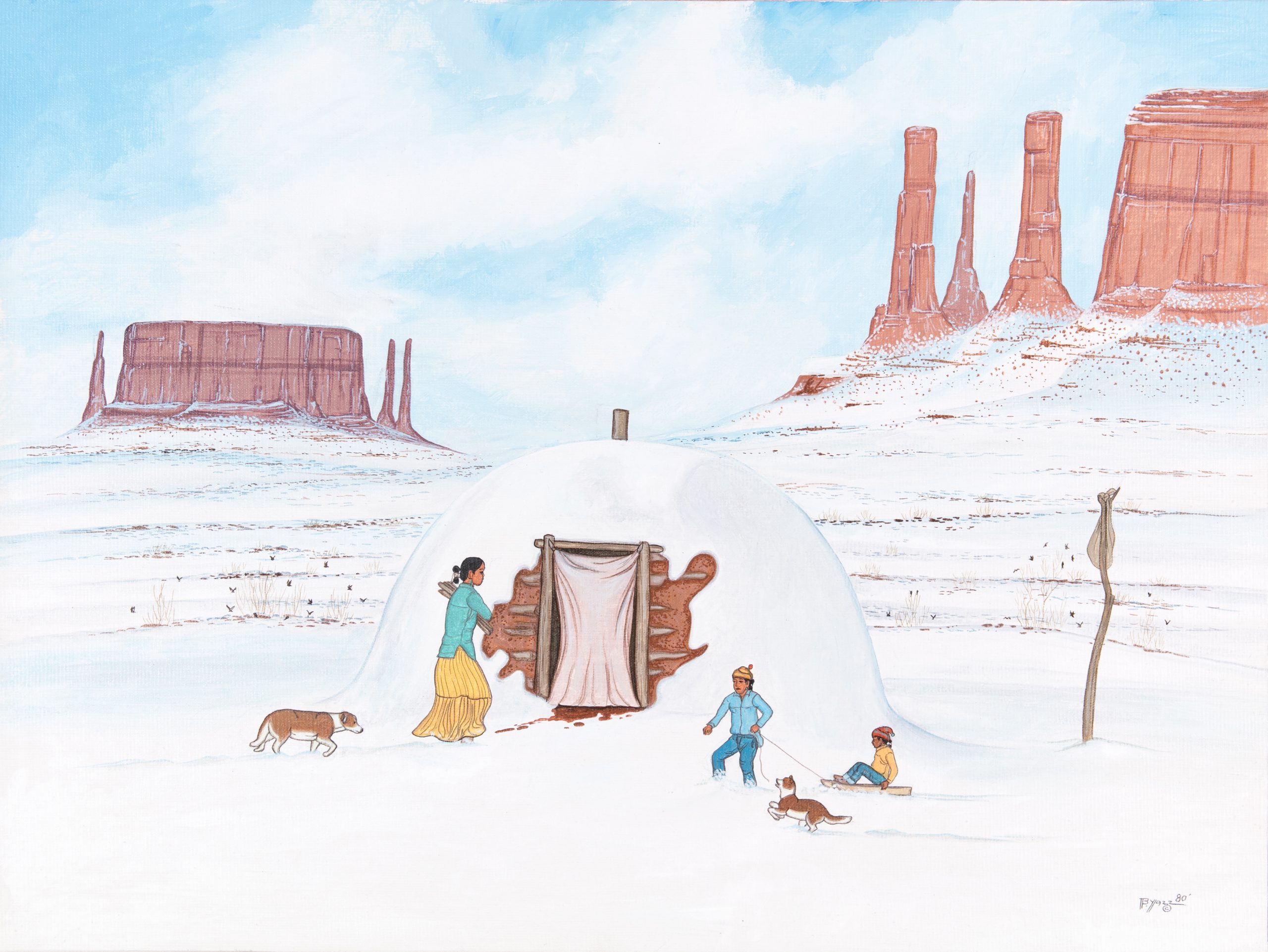

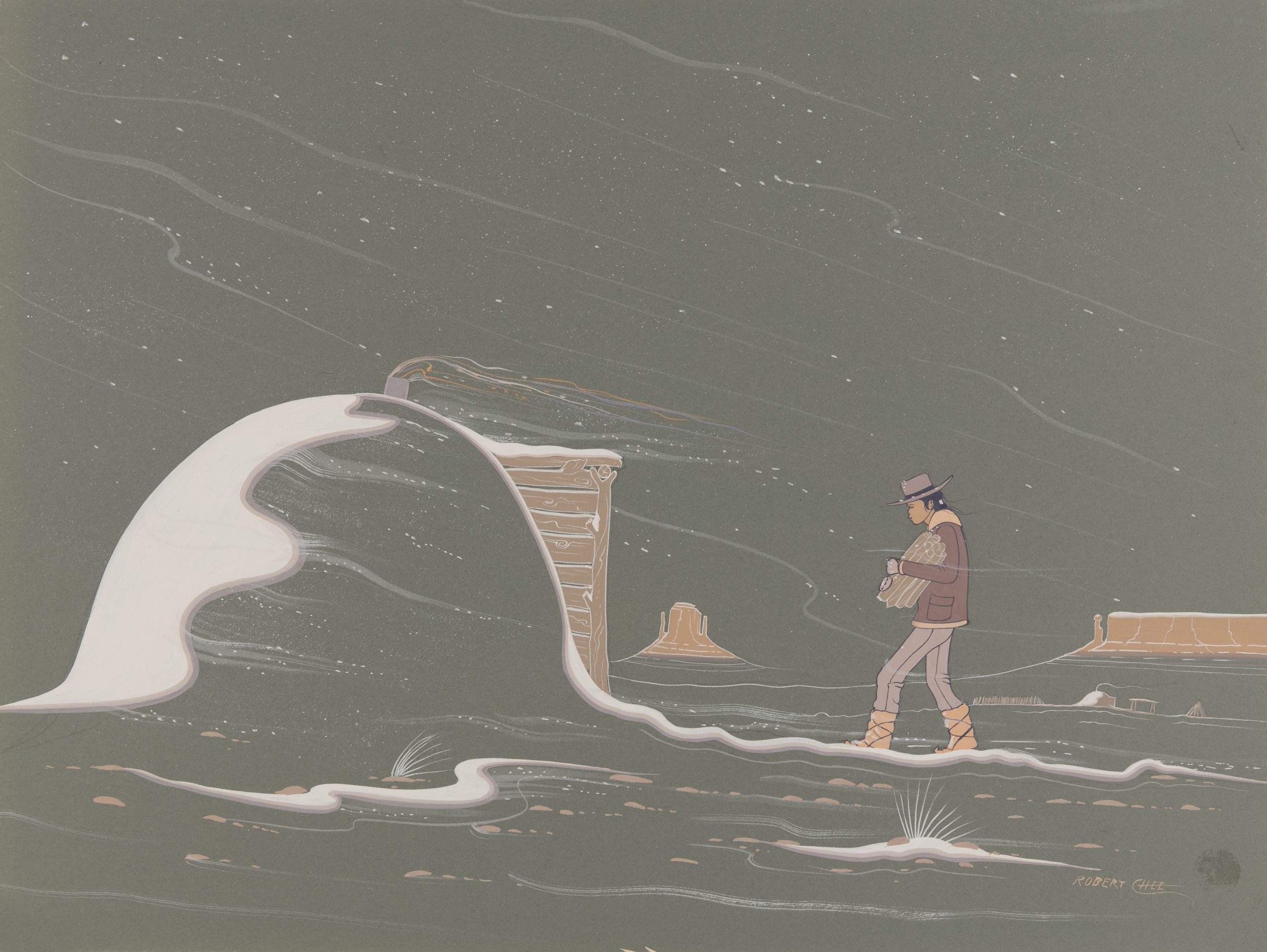

SNOW

In Eurocentric depictions of Southwestern landscapes, viewers often see paintings of dry desert canyons and mountains during high noon with clear skies in bright vibrant colors or sunsets in a hazy romantic glow. Artists rarely depict snow in landscape scenes of the Southwest; rarer still, are depictions of how Indigenous people survive in a winter environment. These four works, all done by Diné artists, capture life on the southern Colorado Plateau during winter months. In the higher elevations of the snow-capped mountains on the Plateau, winter is bitterly cold. In all of these paintings, Yazz and Robert Chee illustrate the resilience of their community whether it be through hunting, traveling or daily life around the hogan. These honest depictions of everyday survival were not illustrated by artists like the Taos Society of Artists likely due both to the snowy landscape not fitting the Southwestern aesthetic they hoped to capture, and because they did not live in the area during the winter. Many Anglo American artists only maintained summer homes and studios and, thus, would miss the winter months. For Indigenous artists like Yazz, experiencing this type of scenery with snow in their ancestral canyon is a timeless event and something to be celebrated.

“A lot of people ask me if I have a message to give through my paintings. I just paint what I see.”[11]

CONTEMPORARY PIECES

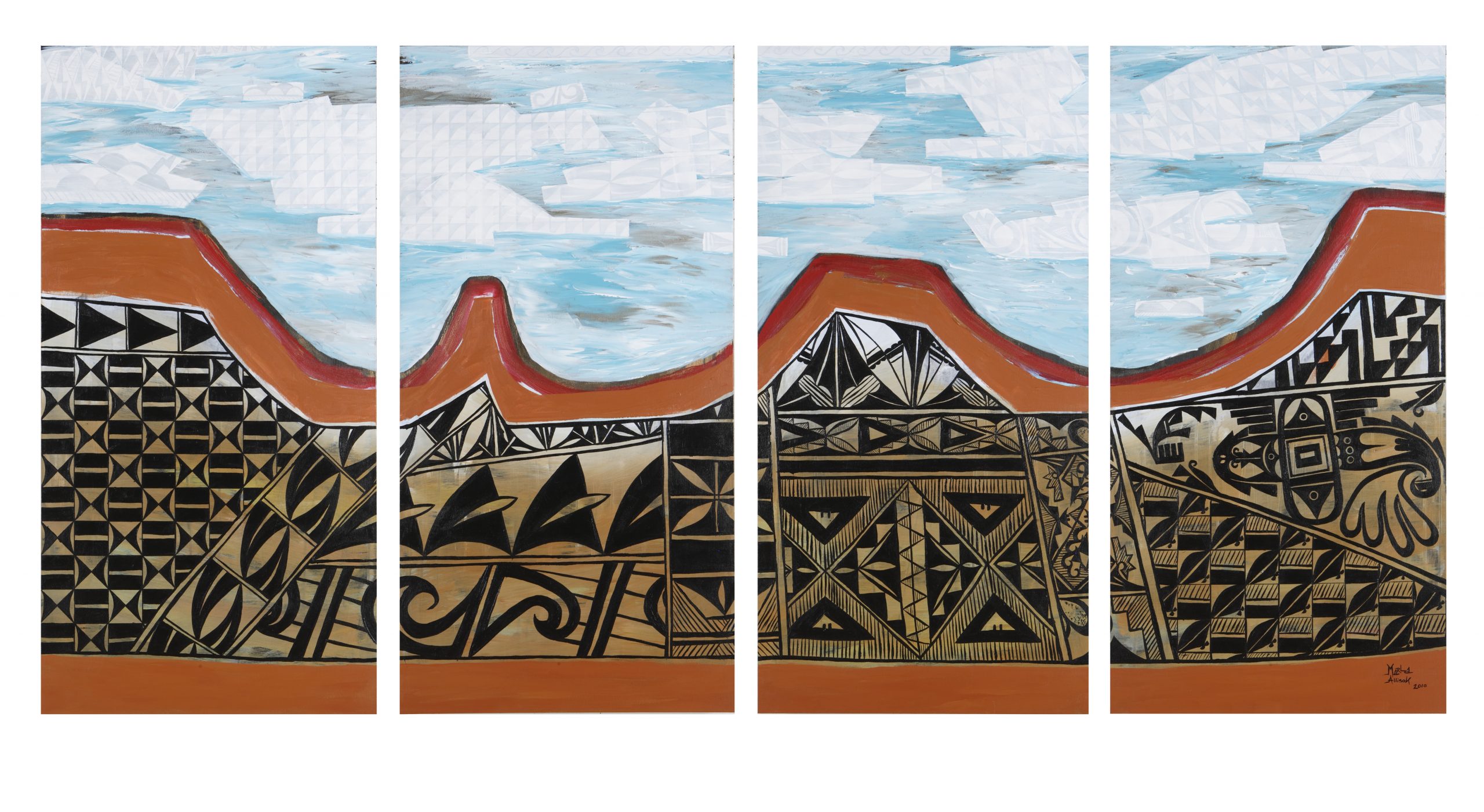

“The cultural landscape is a living spirit. It is changing and it is in every living being. The cultural landscape calls us her children and grandchildren.”

– William B. Tsosie

“This piece speaks to my perspective of preservation, to my indigenous obligation to continue the stewardship role as Hopi sinom (people) of our ancestral lands and to continue the cultural traditions that are in direct correlation to the protection of our essential natural resource. Our lands give purpose to our total existence in indigenous lifeways and “corn” is the Hopi metaphor for our existence. […] It is my hope that acknowledging respect for the land will lead to respect for the people to whom it inherently belongs.”

SAR’s 2010 Eric and Barbara Dobkin Fellowship artist Marla Allison creates work that seamlessly combines different styles and media inspired by artists like Frieda Kahlo, Jean Michel Basquiat, Pablo Picasso, and M.C. Escher but that also reflects Pueblo pottery from Laguna and Hopi. Both of these artists explore new artistic practices and expressions uniquely their own, but they also still retain traditional aspects of their Indigenous heritage and connect with family, tradition, and the inspiration that community provides.

THANK YOU

I first would like to say thank you to everyone at the IARC for helping me put this together. A special thank you to Elysia Poon, Paloma López and Olivia Amaya Ortiz for helping me through the writing process.

I also would like to thank Lomayumtewa K. Ishii and William B. Tsosie Jr for taking the time to write the beautiful quotes used in the final section of the exhibition.

Finally, I would like to thank The Rockwell Museum for allowing me to use the Eanger Irving Couse image for the beginning section of the exhibition.

REFERENCES

[1] Howard, Kathleen, et al. Inventing the Southwest: The Fred Harvey Company and Native American Art. pg IX

[2] Sedgwick, John. “How the Santa Fe Railroad Changed America Forever.”

[3] “The American West, 1865-1900.” The Library of Congress.

[4] To learn more about the white imagination, see American poet Claudia Rankine’s The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind and Citizen: An American Lyric.

[5] Ott, John. “Reform in Redface: The Taos Society of Artists Plays Indian.” pg 81.

[6] “Reform in Redface.” pg 81.

[7] Chevalier, Elise. “Lessons from Dorothy Dunn.” pg 83.

[8] The Kiowa Six were also innovating in a very similar approach around the same time at the University of Oklahoma School of Art in Norman.

[9] Chevalier, Elise. “Lessons from Dorothy Dunn.” pg 90.

[10] Horton, Jessica L. “‘They Sent Me Way Out.” pg 103.

[11] Yazz, Beatien. “Reminiscences.” Yazz: Navajo Painter. pg 71.